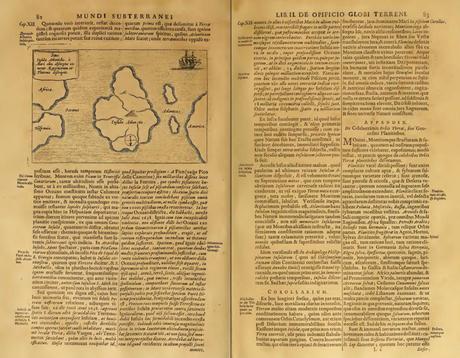

Atlantis, as pictured by Athanasius Kircher in "Mundi Subterranei," 1669

This evening marks the first in a series of three performances of an imaginative and exciting program by the New York Philharmonic, under the leadership of Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos. Carl Orff's Carmina Burana is paired with selections from Manuel de Falla's final (unfinished) work, Atlantida, a "scenic cantata" combining poetic laments for the fall of Atlantis with visions of Columbus' transatlantic voyage on behalf of the Spanish empire. Under the baton of Frühbeck de Burgos, both works were brought to vibrant life by the Philharmonic, in sensual, powerful performances. As I attended the general rehearsal, the following cannot be a review, but I did want to put down some notes on what was a very impressive musical experience. Getting to see the orchestra--and the very fine forces of Orfeón Pamplonés--at work was a treat.De Falla's Atlantida was a work with which I was utterly unfamiliar; the account given by the Philharmonic made a strong case for it as an elegant, evocative, slightly uncanny piece, the hallucinatory imagery of Catalan poetry supported by subtle orchestration. For those of you, Gentle Readers, who may be saying, "But mythology about Columbus?" ...I know. This felt to me, however, like a surprisingly depoliticized piece, despite the rhetoric about Spain resting in the hand of God, etc. The imagery it uses--and more importantly the values it laments and seeks to recreate--are much older than nationalism. The orchestra is concerned not with lines on maps, but with oceans and sky, with the submerged marble palaces of Atlantis, and the fragrant trees and verdant hills of Spain. In evoking these, Frühbeck de Burgos negotiated carefully between passages of great delicacy and confident sweep. In this mysterious mythology, Isabella dreams of a golden bird carrying a hundred-sided ring, after which she begs Columbus to take her jewels and buy swift-winged ships; the queen will array herself in violets and cornflowers. The role of the queen was taken by Emalie Savoy, the tone of her dream becoming more strongly prophetic under Frühbeck de Burgos' guidance.

Wheel of Fortune, from the Codex Buranus

Carl Orff's Carmina Burana, of course, has had its first movement endlessly excerpted and lazily played. But its savage, sensual beauty deserves much better, and with Frühbeck de Burgos, it got it; the first crashing chords raised the hairs on the back of my neck. The ambitious sweep of the work requires excellence from orchestra, chorus, and soloists alike, and this lineup is a remarkable one. In addition to the incisive, exuberant performance of Orfeón Pamplonés, there was the fine work of the Brooklyn Youth Chorus, an impressive slate of youthful soloists in Erin Morley, Nicholas Phan, and Jacques Imbrailo, and not least, the New York Philharmonic itself. Frühbeck de Burgos steered these enormous forces with energy and brio, sensitive both to the fragile delicacy of of some movements in the "Cour d'Amours" and to the wild, bacchanalian fervor of "In Taberna." Erin Morley sang with great sweetness and admirable control of her sound. In his brief, challenging assignment, Nicholas Phan gave a vivid portrayal of the dying swan in "Olim lacus colueram." I really liked the match of his timbre to the piece, and he used the text well. I asked the Beloved Flatmate as we exited whether Jacques Imbrailo had been seducing everyone, or whether I was just susceptible. She said the latter was a distinct possibility. In any case, his warm, plangent baritone was a treat, smoothly navigating between satiric irony, despair, and romantic ardor. The transience of these emotions was mocked as Fortune, empress of the world was hailed with a brutal paean.Addendum: for anyone attending this weekend's performances, a few notes on the text in the surtitles. I can't speak to the representation of the Catalan poetry, although some of the English lines seemed odd, but the handling of the medieval German was clumsy, and the Latin barbaric (ha! Medievalist joke. Sorry.) Those "forest soldiers" whose health is drunk in the tavern? Those would be outlaws. Sure, suave labor can be translated as, er, "suave labor," but that's not what "the sweet work of Venus" means. Lost is the dramatic heightening of verbs in "Totus floreo," and several of the tavern songs have liturgical echoes which were likewise glossed over. (Liturgical satire: hilarious in the thirteenth century.) I'm sure there are ways to bring out the classical allusions of the pastoral poetry for a modern audience, with some thought and care. Sigh. Apologies if this seems like pedantry, but the original text is vibrant and sly and sexy in ways that the translations weren't.