Introduction

Friends of Justice, the organization I lead, has been in existence for twenty-two years. In that time, I have never attempted to compress the full scope of our work into one presentation. But I’m going to try it today. Or, I will come as close to telling the complete story as is humanly possible. I will be oversimplifying complex matters and leaving out a lot of important information. I will confine myself to just four cases we have impacted. This isn’t just about what happened in Tulia, Texas, Jena, Louisiana, or Winona Mississippi; the legal train wrecks I will be describing are symptomatic of a systemic problem.

At root, the problem is theological. According to Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann, “The prophetic tasks of the church are to tell the truth in a society that lives in illusion, grieve in a society that practices denial, and express hope in a society that lives in despair.”

Brueggemann isn’t saying that there are bad people out there who live in illusion, who practice denial, and who, consequently, live in despair. He is saying we’re all like that. Criminals are like that, sheriffs and district attorneys are like that, judges and jurors are like that, and religious people who show up for church every Sunday are like that.

We tend to think of court rooms and church sanctuaries as places where good people confront bad people. The criminal justice system assumes that police officers, prosecutors, judges and jurors can be trusted to act in good faith, to exercise sound judgement, and to dispense clear-eyed justice. But if Brueggemann is right, we should expect our courtrooms (and our churches) to be staggering under the weight of illusion, denial and despair. And, if that’s true, justice will elude us as often as not.

Early in my work with Friends of Justice, I concluded that white racial resentment is the most powerful force in American politics, American religion, and the American criminal justice system. I’m not saying that white racial resentment is the only factor in play; it is simply the most powerful.

John Grisham started out as a Mississippi lawyer, but quickly realized he could make a lot more money churning out legal thrillers.

“I grew up in the Jim Crow South,” Grisham recently told the New York Times. “A very segregated, racist society was almost in my DNA . . . The Baptist Church was that way too back then. I’ve come a long way. I have a lot of friends and even kinfolk who never tried to move beyond the racism. But I try every day. It’s been an ongoing, gradual transformation.”

Grisham went on to say that, until he understood the culture of his raising, he couldn’t understand what was happening in the courtroom. The same could be said about our churches.

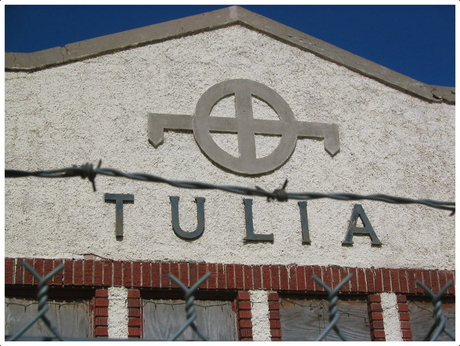

Tulia

Friends of Justice came into being quite by accident. In 1999, law enforcement announced that forty-seven men and women had been arrested in the Texas Panhandle town of Tulia.

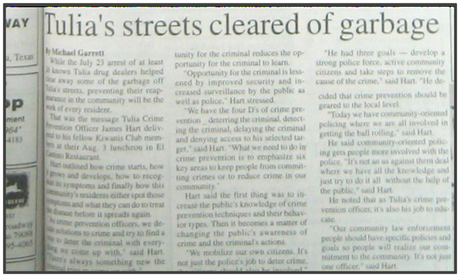

The local newspaper called the defendants “a cancer on the community”. The headline read, “Tulia’s streets cleared of garbage”.

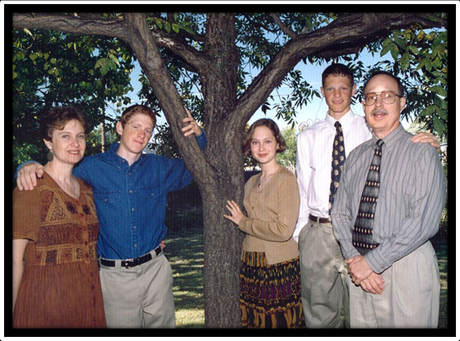

I had moved to Tulia a year earlier with my wife, Nancy. Our daughter, Lydia was entering college; our son Adam was in High school while Amos was in Junior High. Tulia was Nancy’s home town.

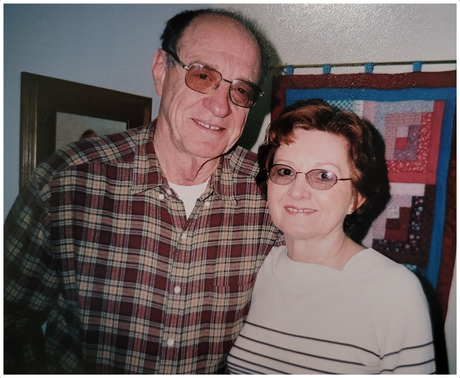

We were soon followed by Nancy’s parents, Charles and Patricia Kiker. They too had grown up in the countryside around Tulia and had decided to retire there. Nancy and I came along for the ride.

We were soon followed by Nancy’s parents, Charles and Patricia Kiker. They too had grown up in the countryside around Tulia and had decided to retire there. Nancy and I came along for the ride.

Our initial concern with the drug sting was theological. We assumed that everyone was guilty as charged, but, as the saying goes, “God don’t make no garbage!” Referring to the defendants as human trash and “scumbags” was offensive to us.

It was also clear that the newspaper editor didn’t know any more about the men and women arrested in the drug bust than we did. But he thought he knew them. And if he thought that, so did everybody else in town.

So, we did a little poking around. The names and addresses of the defendants were all listed in the newspaper, so we decided to talk to their families. And that’s when we encountered a counter-narrative. Many of the people arrested said they had never met the undercover officer in question. Others, suspicious that the skinny stranger was “the law”, had run him off when he kept asking for drugs.

It was quickly apparent that the defendants were either Black or were immersed in the local Black community.

Then we talked to a sympathetic defense attorney. He told us the undercover officer had been arrested in the middle of the eighteen-month operation by the very sheriff who had hired him. It seemed he had left his last job in law enforcement owing local merchants over $10,000. When the undercover man told the sheriff in Swisher County that he had “taken care of it” he was sent back to the streets, no questions asked.

Finally, we learned that nothing connected the defendants to the little baggies of drugs displayed at trial but the uncorroborated word of the undercover cop.

The cases quickly went to trial. Juries handed down the maximum sentences allowed by law: twenty-five years, forty-five years, sixty years, ninety years. One man was given six consecutive ninety-nine-year sentences. After that, people started lining up for plea bargains.

No one was surprised when Senator John Cornyn named Tom Coleman “Texas Lawman of the Year.”

Friends of Justice began as the Beans, the Kikers, a four-hundred-pound farmer, and several dozen family members of the accused, people like Freddie Brookins, who lost a son and Thelma Johnson, who was related to half the accused in one way or another. We met at the Beans home every Sunday night, singing spirituals, reading letters from prison and plotting our response.

The big question was why anyone with a lick of sense would believe the dim-witted undercover agent. Even when juries learned of his legal problems, they hung on his every word.

When people see the world through a racist lens, they will approach every criminal case with certain pre-conceptions which, taken together, constitute a false narrative. If the accused is guilty as charged, a false narrative can double a sentence. If the accused is innocent, the false narrative issues in a wrongful conviction.

In Tulia, the false narrative went something like this. There was a time when people worked hard for a living, but nowadays everybody’s just looking for a handout, especially young Black males. They’re too lazy to work, so they mess around with white girls and they sell drugs for easy money. And nobody does anything about it.

Friends of Justice counters false narratives with counter-narratives that tell the truth, grieve with those who grieve, and point the way to hope.

I am NOT a lawyer. By training and experience, I am a pastor, a hospice chaplain and a church historian. The work Friends of Justice does is no substitute for skilled legal representation. But a good counter-narrative takes hundreds of hours of investigation, research and reflection, and few lawyers have time for that. Even if they did, courtroom protocol places strict limits on the kind of story you can tell.

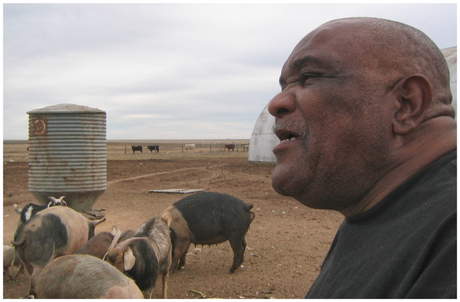

A good counter-narrative requires researching the racial history of the community (facts that are considered legally irrelevant). Tulia was a largely monochrome community until irrigated agriculture revolutionized the economy at mid-century. A sudden need for field labor brought share croppers from East Texas. They lived in abandoned shacks and railway cars and subsisted in third-world conditions across the tracks in a ramshackle community white folks called the Sunset Addition (when they were feeling polite).

When agriculture was automated and the irrigation water began to recede, the need for farm labor plummeted. Young people tried to find greener pastures, but many remained. Tulia was all they knew. Many were celebrated for their exploits on the football field and the basketball court, but after graduation, they were instantly regarded as potential criminals. Those who couldn’t make it in the city, returned, bouncing from one part-time seasonal job to the next.

Then came the war on drugs. Tulia received a grant from the narcotics task force in Amarillo and hired the only man who interviewed for the $17,000 yearly salary.

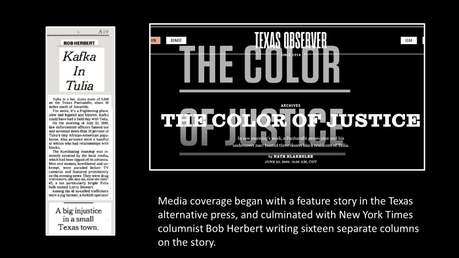

We mailed our counter-narrative to the Texas Observer and waited. A reporter, fresh out of journalism school, wrote a feature-length article. Two sisters from Manhattan worked our narrative into a brief documentary. Vanita Gupta, now the associate Attorney General, had just graduated from law school when she viewed the documentary. Vanita came to Tulia and returned to New York with a suitcase-full of evidence which she shared with the Legal Defense Fund of the NAACP. Then Bob Herbert, a columnist with the New York Times wrote sixteen separate columns on the story.

Before it was over, two of the most prestigious law firms in America were working for the Tulia defendants on pro bono basis.

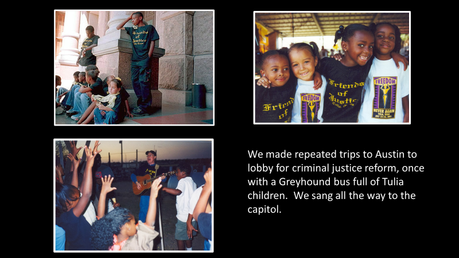

While all this was going on, Nancy and I welcomed three school-age children, orphaned by the drug sting, into our home. Friends of Justice made repeated trips to Austin to lobby for criminal justice reform, once with a Greyhound bus full of Tulia children. We sang all the way to the capitol.

On the second anniversary of the drug sting, we held a Never Again rally in Tulia. At midnight, 300 people from all over America prayed on the courthouse steps in Tulia.

At the conclusion of a week-long evidentiary hearing at the Swisher County Courthouse, visiting Judge Ron Chapman found that undercover agent Tom Coleman was “not credible under oath.”

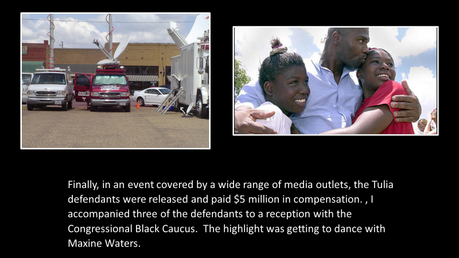

In an event covered by a wide range of media outlets, the Tulia defendants were released and paid $5 million in compensation. Tom Coleman was indicted for perjury.

A few weeks later, I accompanied three of the defendants to a reception with the Congressional Black Caucus. The highlight was watching these young men dancing with Maxine Waters.

By the time the national media latched onto the story, nobody knew about Friends of Justice. And yet, had we not created a credible counter-narrative, nothing would have happened. Tom Coleman would still be 1999’s Texas Lawman of the Year. This is a predictable pattern. The counter-narratives we create are best understood as a foundation for other builders. In most cases, overturning a wrongful conviction requires national media attention, dedicated pro bono legal work, and some good luck. And when the media people and the attorneys have played their part in the process, they are credited with victory. When the house is built, nobody comments on the foundation. Learning to work without recognition is a prerequisite for the work we do. The first time our efforts were overlooked, it really stung. Now, we see it as an unavoidable part of the process.

Church Point

After six years of struggle in Tulia, I was ready to get back to my normal life, when I received a call from Ann Colomb. Ann and three of her sons had been charged with running a multi-million-dollar drug operation out of their modest FHA bungalow in Church Point, a community just north of Lafayette, Louisiana.

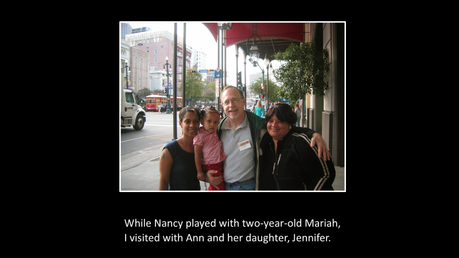

Since Nancy and I were attending a conference in New Orleans, we arranged to meet there. While Nancy played with two-year-old Mariah, I visited with Ann and her daughter, Jennifer.

The story they told had a familiar ring. Ann’s sons, Edward and Danny, appeared to be the primary targets. Danny had set school records as a running back a few years earlier, while Edward had excelled at basketball. Both boys were at the center of a large social circle of white and Black students, and in a highly segregated town, this made them dangerous.

In subsequent visits to Church Point, I visited with some of the girls Anne’s sons had dated back in the day. They told me how their parents threatened to disown them. One girl was placed in a Catholic school in a neighboring town so she couldn’t date Black boys.

The police harassment had been unremitting. On several occasions, Edward and Danny had been arrested and charged with drug-related crimes. Defense attorneys told the boys to accept plea bargains, but Anne wouldn’t have it. Eventually, charges would be dropped for lack of evidence; local officials had been bluffing.

All the evidence in the case came from thirty-one federal prison inmates scattered throughout Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi. They had once been part of a massive Houston drug ring that controlled the crack cocaine traffic in the Lafayette area, and were serving multi-decade sentences without parole. But they could cut their sentences by providing information the government could use to bust other dealers.

Anne’s sons came to the attention of the feds when Brett Grayson, an assistant US Attorney in Lafayette, hired a retired police officer who once worked in Church Point. Grayson was on the lookout for easy targets (narcotics conspiracy cases are easy to prosecute once you get the hang of it). His assistant told him about Anne Colomb and her sons. The two men traveled to a string of federal prisons asking inmates if they had anything on Anne’s boys.

Because this was a federal case, the government had to furnish defense counsel with all the letters that changed hands between inmates. Two things were clear as I read this correspondence: first, none of these men possessed real knowledge of Anne’s boys. Second, they intended to remedy that problem.

In these letters, inmates asked one another for information that would enable them to cobble together a believable story. They were sharing dates and times so their accounts would harmonize.

The judge in the case, Tucker Melancon, didn’t want this kind of testimony in his courtroom; but he was overruled by a panel of fifth circuit judges. The government promised to drop the charges against Anne if her sons would take a plea bargain. True to character, she refused the deal.

I told Anne that a case this insanely weak would never go before a jury. But one morning, Anne called, her voice shaking with emotion. “We’re going to trial in two days,” she said. I jumped in the car and headed for Louisiana.

The trial unfolded over ten days. If the witnesses were all telling the truth, the Colomb family would have raked in at least five million dollars from their nefarious activities. Yet, to cite just one example, Danny was driving a car during this period that was so old his friends had to push him before it would start. Danny was working construction during the day and going to trade school at night: hardly the M.O. of a drug kingpin.

I had been blogging about the case for months, but had been unable to stir up much media interest. So, when court adjourned for the day, I would drive to the downtown library and tap out a report on one of their computers. After a couple of days, the online edition of the Lafayette newspaper started linking to my posts and a lively online debate ensued. Most readers were certain that everyone was guilty as charged because, if they weren’t, they wouldn’t be on trial.

Danny and Edward were both married, and their wives and children sat stoically in the courtroom fearing the worst. Danny, a devout Catholic, began each day in prayer at the church down the street from the courthouse. They were staying brave for one another, but the sense of desperation was growing.

Midway through the parade of inmate witnesses, the prosecutor received a letter from Quinn Alex, a Texas inmate. Alex was angry. Working through his girlfriend in the free world, he had paid another inmate $2200 for information about the Colombs. But his cellmate had been transferred without providing any information, so Quinn Alex hadn’t been able to testify. He wanted his money back.

In accordance with legal protocol, Quinn Alex’s letter was shared with defense counsel. They moved for a mistrial. The judge, certain that the Fifth Circuit would overrule him, demanded that Quinn Alex be brought to Lafayette, but he allowed the trial to continue.

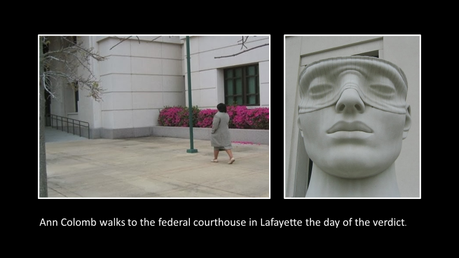

The night before the verdict, just as I was ready to nod off, I was gripped by the painful realization that Anne and her sons were doomed. I felt it in my bones. Slipping out of Anne’s guest bed, I knelt on the carpeted floor and prayed. The next morning, Anne got herself dressed for court, and we drove to the federal courthouse in Lafayette. There was little conversation.

All four defendants were found guilty and sentenced to between ten and twenty years without parole. The prosecutor announced that, because the Colomb home had been the center of a massive drug ring, he intended to seize it. A collective gasp, followed by a groan, filled the courtroom. Wives, husbands and children were glued to one another in grief.

I spent the rest of that night shuttling from home to home. The grief was palpable. We were praying for a miracle.

Quinn Alex, the federal inmate who had been cheated out of $2200, remained in custody in Lafayette. When he expressed curiosity about the trial, someone printed off my blog posts. Then Danny invited him to an impromptu Bible study.

“I don’t think you’re no drug dealer,” Alex told Danny, “And I can’t believe your mama is either.”

Returning to his cell, Quinn Alex wrote a letter to Danny’s defense attorney describing secret gatherings in which inmates shared information. He admitted that neither he, nor any of the government’s witnesses, had any first-hand knowledge of Anne and her boys.

A hearing into the matter took place August 31, 2006. The government and defense counsel both had their say. The judge asked the prosecutor if he thought his witnesses were credible. The prosecutor said he didn’t worry too much about witness credibility; that was for the jury to assess. Judge Melancon ordered Anne, Danny, Edward and Sammie released immediately.

Natasha Colomb embraced her Edward and Elizabeth Davis rushed to her Danny. Elizabeth, who was carrying Danny’s child, hadn’t been able to stay in the house Danny had built for her while he was locked up. Now she took the ring she had been wearing close to her heart and placed it back on Danny’s finger where it belonged.

“Hey y’all,” Danny called out, “we need to thank God for this miracle.” Thirty men, women, and children joined hands in a big circle. Danny led us in a short, workingman’s prayer followed by the familiar words, “Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy name . . .”

A few days later, Judge Melancon released his written ruling. “Occurrences in this case,” he said, “suggest that a systemic problem may exist within the penal facilities operated by the Federal Bureau of Prisons. In the view of the trial judge, the issues raised herein are so substantial and grave that those who have the power and the authority to do so need to address them.”

The case never attracted much media interest. Radley Balko, then with Reason magazine, now with the Washington Post, wrote a feature story. More significantly, the case attracted considerable attention in the legal world. In 2018, Alexandra Natapoff, a nationally recognized authority on inmate testimony, used the Colomb case as a chilling illustration of how things can go wrong. “The Colomb case,” she wrote, “is just one example of how the use of criminal informants, and jailhouse informants in particular, distorts large swaths of our criminal justice process.

Jena

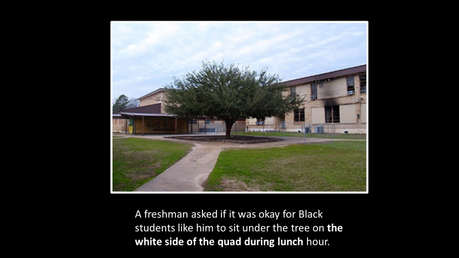

On the same day Anne Colomb and her boys were vindicated, a routine school assembly unfolded at the high school in Jena, Louisiana. In accordance with local custom, Black students sat on one side of the school auditorium; white students on the other. When the principal asked if the students had any questions, a freshman asked if it was okay for Black students like him to sit under the tree on the white side of the quad during lunch hour. Since there was no formal rule designating the tree in question as a “white tree”, the principal said, “of course”.

The following day, September 1, 2006, three nooses were found hanging from the tree in the quad. Two of the nooses were black and one was gold: the Jena High School colors.

On Tuesday night, September 5, 2006, a group of black parents convened at the L&A Missionary Baptist Church in Jena to discuss their response to what they considered a hate crime and an act of intimidation.

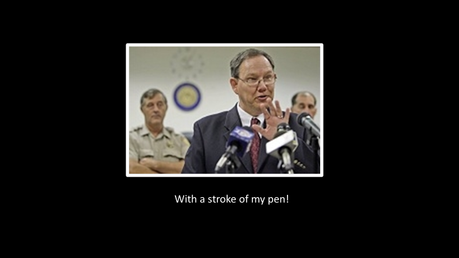

When Black students staged an impromptu protest under the tree on Wednesday, September 6, 2006, a school assembly was hastily convened. Flanked by police officers, District Attorney Reed Walters warned Black students that additional unrest would be treated as a criminal matter. According to multiple witnesses, the District Attorney warned the student protestors that, “I can make your lives disappear with a stroke of my pen.”

On Thursday, September 7th, police officers patrolled the halls of Jena High School and on Friday, September 8th, the school was placed on full lockdown. Confrontations between Black and white students went off-campus as sporadic fights broke out between Black football players and members of the all-white rodeo team.

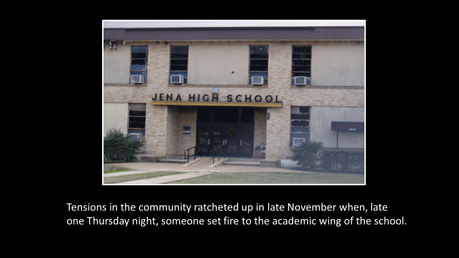

The tension in the community ratcheted up in late November when, late one Thursday night, someone set fire to the academic wing of the school. In the white community, it was widely believed (wrongly, it turned out) that Black students were the culprits.

During the weekend, a white student threatened several Black football players with a sawed-off shotgun. On another occasion, a Black student attempting to enter a community dance was assaulted by white students wielding beer bottles. He was punched and kicked before adults broke up the fight.

When classes resumed the following Monday, the atmosphere was toxic. Shortly after the lunch hour, Justin Barker, a white student from the same social circle that hung the nooses at the beginning of the school year, was knocked to the ground and, witnesses said, kicked and stomped by several Black students.

Within an hour, six Black males had been arrested and charged with conspiracy to commit second-degree murder—charges carrying a maximum sentence of life in prison.

It was at this point that Friends of Justice was asked to investigate. I told the attorney who called me that I wouldn’t be intruding into the situation unless the parents of the accused students asked me directly. Within five minutes, they were on the phone, begging me to come to Jena.

Upon arrival, I made a tour of the white community, asking the editor of the Jena Times, the pastor of First Baptist Church, and anyone else I could find to give me their understanding of the situation. They were convinced that the defendants were all guilty as charged.

I dropped by the courthouse and asked for court records on the case which, to my delight, included all the hand-written eye witness accounts taken from the students and teachers who witnessed the scene. I paid an exorbitant price for photocopies and went to my motel room. Some of the witnesses named one or more of the accused, but several other Black students were named, and many witnesses said it happened so quickly they had no idea who was responsible.

Justin Barker, though badly bruised, was examined and released from the hospital the same day.

In the Black community, the defendants were already being called “the Jena 6”. They all denied involvement.

Having read the eye witness statements, I had no opinion as to guilt or innocence. What concerned me was that the assault on Justin Barker was being considered in pristine isolation from the toxic environment in which it occurred. It was as if the Black students just decided to pick on a randomly-selected white student for the fun of it.

The more I learned from Black parents and students, the more convinced I became that the failure of white school officials to take the concerns of the Black community seriously had precipitated a dangerous social situation. If guilt could be proven beyond a reasonable doubt, I felt, the defendants should be punished; but they certainly didn’t deserve charges which, if sustained, would place them in prison for a quarter century without parole.

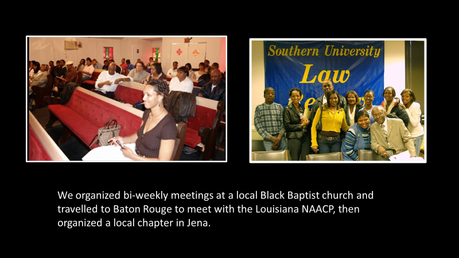

I composed a counter-narrative titled “Responding to the Crisis in Jena, Louisiana” and sent it to journalists who had written seriously about racial justice. Next, I called up the Southern Poverty Law Center and asked if they would foot the bill for a first-rate civil rights attorney. As word spread through the advocacy community, other attorneys asked to get involved. Before long, each defendant had first-rate legal representation and a coordinated legal strategy was in the works. Working with the local Black community, I organized bi-weekly protest meetings at a local Black Baptist church and traveled to Baton Rouge to meet with the Louisiana NAACP, then organized a local chapter in Jena.

Then Howard Witt, a reporter from the Chicago Tribune, called me up. He had read my account, he said, and would like to do a story. Witt flew to the central Louisiana town of 3,000, conducted a round of interviews, and wrote a story which closely followed my initial account. He would file a dozen additional stories before he was done. With a compelling counter-narrative on the table, DA Reed Walters was forced to scale back the charges against the Jena 6 again and again.

Then my narrative hit the Black blogosphere. The story seemed to capture the imagination of Black churches and college students across the nation. People could relate to the plight of the Jena 6 because something similar had happened to a brother, a boyfriend, a cousin, or a close associate.

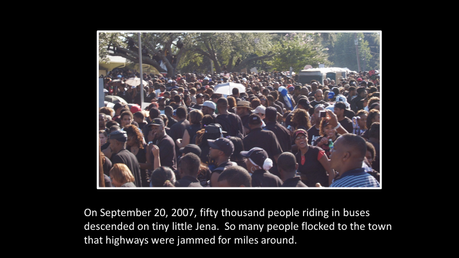

On September 20, 2007, fifty thousand people riding in buses descended on tiny little Jena. So many people flocked to the town that highways were jammed for miles around. Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton were there, as were a list of Black rappers and media celebrities I had never heard of. Most protesters wore black T-shirts emblazoned with graphic portrayals of the school yard tree. The event, though chaotic at times, was completely non-violent.

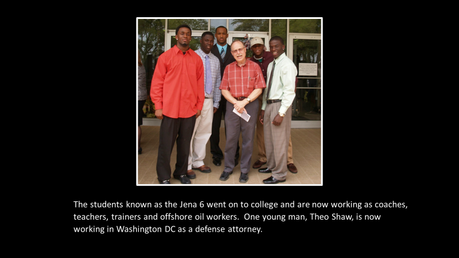

Overwhelmed by the publicity, the DA stipulated that if the defendants would apologize to Justin Barker and pay his modest medical bills, he would drop the charges. Defense attorneys told their clients to take the deal. Instead of wasting away in prison, the students known as the Jena 6 went on to college and are now working as college football coaches, teachers, off shore oil workers and trainers. One young man, Theo Shaw, is now practicing law in Washington DC.

The Jena 6 story became an issue in the 2008 Democratic primary as both Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama released statements of concern. “When a noose hangs from a schoolyard tree in the 21st century,” Obama said, “and young men are treated in a way that is not equal nor just, it is not just an offense to the people of Jena or to the African-American community, it is an offense to the ideals we hold as Americans. I renew my call for the District Attorney to drop the excessive charges filed in this case, and I will continue my decades-long fight against injustice and division as President.”

Winona

After giving a presentation on the Jena 6 at a legal conference in New Orleans, an attorney asked me if I would mind looking into the case of a young man from Winona, Mississippi. Curtis Flowers stood accused of murdering four innocent people at a furniture store back in 1996. He had been to trial five times on the same charges. Winona, the attorney informed me, was the town where civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer was beaten half to death back in 1963.

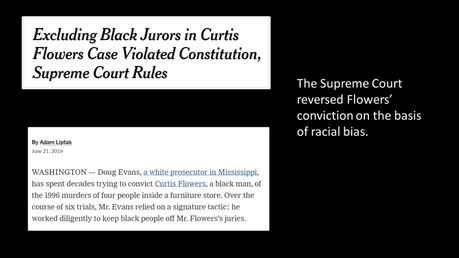

All-white juries quickly convicted Curtis, but the Mississippi Supreme Court vacated two convictions because Evans broke the rules to keep people of color off the jury.

Then a jury was selected comprised of five Blacks and seven whites. All five Black jurors voted to acquit; all seven white jurors voted to convict.

In the fifth trial in 2008, James Bibbs, a Black school principal, was the only hold-out against conviction. The DA was so incensed, he hauled Bibbs in front of the judge and accused him of perjury. The charges were eventually thrown out, but Winona’s Black community got the message.

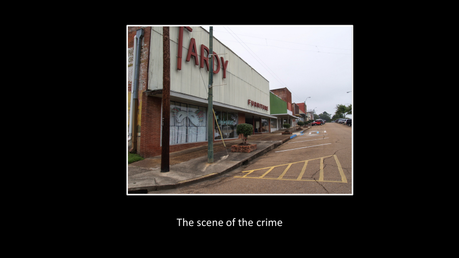

Curtis Flowers had worked at Tardy Furniture for three days, but was replaced when he didn’t return for work after the July 4th weekend. According to the state’s theory of the crime, Flowers was so incensed by this news that he stole a handgun from the glove compartment of a car, walked half a mile to the scene of the crime, murdered four people in cold blood, then returned home by a different route.

The state’s case against Flowers consisted of a dozen witnesses who claimed to have seen him on the morning of the murder walking to or from the crime scene. In addition, an inmate at Parchman prison testified that Curtis had admitted to the crime while the two men were locked up together. He recanted this testimony, apologizing to the Flowers family, then returned to his original story.

Only later did we learn that investigators had gone door-to-door along the suspected route, holding a picture of Curtis Flowers in one hand, and a leaflet promising $30,000 dollars for information leading to a conviction in the other.

After spending several weeks reading five lengthy trial transcripts, interviewing family members, local media, neighbors, and defense counsel, I was convinced that Curtis was innocent. Whoever committed this dreadful crime, I concluded, was a broken soul who killed because he liked it.

A good-natured gospel singer from a devout family, Curtis Flowers didn’t fit the cold-killer profile, but only the Black community knew that. White residents easily concluded that Flowers was just another one of those Black thugs they had seen on television.

When Curtis went to trial for the sixth time in June of 2010, seating was divided along racial lines and the atmosphere was tense.

I had traveled to Winona with my daughter, Lydia (then a sociology professor at Baylor) and we were joined by Lili Ibarra, a young attorney from Boston who had helped us with the Tulia case. We stayed at the Holiday Inn until Lola Flowers insisted we stay with her.

I had been able to interest CNN in the case, so Lola and Archie Flowers and the victims’ families were allowed to give statements to a national audience. The sight of a CNN truck parked outside the courthouse, I was told, had unnerved the judge and prosecutor. Still, when a jury of eleven whites was seated, I knew the outcome. I had seen this movie before.

Every night, I wrote a blog post describing the drama inside the courtroom. A young Black attorney working with the defense was stopped by police as she drove to the courthouse. Apparently, a professionally-dressed Black woman made the officer nervous. When she complained to the judge, he accused her of inventing the incident for the media.

I could tell from the nasty comments that some of the victims’ families were reading my stuff. One man, accompanied by two of his sons, started questioning my motives to my face. He referred to Lydia and Lilly as my harem. He had the luxury of venting; I did not.

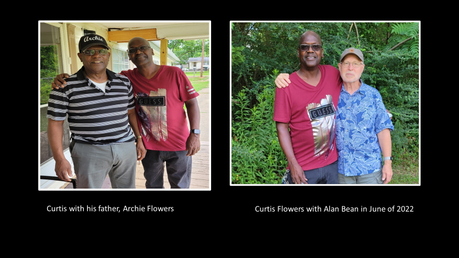

Lola and Archie Flowers had been visiting Curtis every two weeks (as often as Parchman prison allowed), and, when Curtis was convicted and led from the courtroom, they continued this practice. Moments after the trial ended, the local sheriff approached me. “If I was you,” he drawled, “I’d get out of town as quickly as possible.” Lydia and I complied.

An increasingly conservative Mississippi Supreme Court upheld the conviction and the case entered the federal appeals arena. Now Curtis was being represented by some of the best legal minds in the business. They researched the case by reading trial transcripts supplemented by my counter-narrative.

I kept writing about the case, eventually producing over thirty lengthy blog posts about the social and historical context of the case. I saw what happened to Curtis as an extension of the civil rights struggle in the Mississippi Delta.

Then, in late 2016, I received a call from Madelleine Baron. She and her team had produced a highly-regarded podcast called In the Dark. They had read everything I had written on the case and were planning to devote an entire season to the Flowers saga. They spent two full days with me in Arlington, plying me with questions.

A team of four investigators camped out in Winona for the better part of a year. They interviewed and re-interviewed all the witnesses, family members of the victims, and dozens of people on both sides of racial divide. They followed my narrative, arriving at conclusions that were obvious to anyone who had examined the story closely.

Eventually, one of the state’s eye witnesses recanted, then another. They told the police they weren’t sure if they saw Curtis on the morning of the crime, but after repeated interviews, they had caved to pressure. Once their names were signed to a witness statement, they were threatened with perjury if they changed the story.

In the end, even the jailhouse snitch admitted that he concocted a false narrative in exchange for lenient treatment.

By the time In the Dark was through, virtually every eye witness had recanted their testimony. Twenty episodes had been downloaded by an astounding 40 million listeners and In the Dark was the recipient of the prestigious Peabody award.

The Supreme Court reversed Flowers’ conviction on the basis of racial bias. “The State’s relentless, determined effort to rid the jury of black individuals,” the majority opinion read, “strongly suggests that the State wanted to try Flowers before a jury with as few black jurors as possible, and ideally before an all-white jury.”

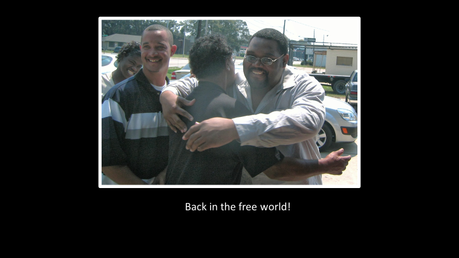

Eventually, a beleaguered Doug Evans kicked the case over to the Mississippi Attorney General, all charges were dropped and, twenty-one years after his initial arrest, Curtis Flowers was a free man.

Only then did the national media take an interest. Suddenly, every venue from Sixty Minutes to the New York Times wanted a piece of the action.

Tragically, Lola Flowers died just days after the Supreme Court ruling. I talked to her by phone on the last night of her life. She was in pain, she told me, “But I know Curtis is coming home, and that’s all that matters.” The state of Mississippi wouldn’t allow Mr. Flowers to attend his mothers’ funeral. But he’s back in the free world, adjusting to cell phones, and spending as much time fishing as he can spare. “It relaxes me,” he told me in mid-June. “It keeps my mind off my troubles.”

In 2021, Curtis Flowers sued prosecutor Doug Evans. In November of 2022, Evans ran for County Judge but was soundly defeated.

Conclusion

There is a tendency to blame what happened in Tulia, Church Point, Jena and Winona on villainous prosecutors, but it takes a village to convict an innocent man. It is tempting to believe these communities are isolated pools of vestigial racism, backwater throwbacks to an era that is mercifully dead and gone. But these cases, and recent Supreme Court decisions, speak to the social sickness of this present moment.

Yes, our churches should pay more attention to the criminal justice system. No question. But we will never do that until we acknowledge our own brokenness. “The Church must come out of its stagnation,” Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote from a gestapo prison cell. “We must move out again into the open air of intellectual discussion with the world, and risk saying controversial things, if we are to get down to the serious problems of life.”

We are not the solution; the gospel of Jesus Christ is the solution. And so, I leave you with Brother Brueggemann’s prophetic tasks of the church: “to tell the truth in a society that lives in illusion, grieve in a society that practices denial, and express hope in a society that lives in despair.”