I came across an utterly fascinating case study on Twitter the other day (via Mo Costandi; see this video too):

I came across an utterly fascinating case study on Twitter the other day (via Mo Costandi; see this video too):

Rare brain condition leaves woman seeing world upside down

Bojana Danilovic has what you might call a unique worldview. Due to a rare condition, she sees everything upside down, all the time.

The 28-year-old Serbian council employee uses an upside down monitor at work and relaxes at home in front of an upside down television stacked on top of the normal one that the rest of her family watches.

"It may look incredible to other people but to me it's completely normal," Danilovic told local newspaper Blic.

"I was born that way. It's just the way I see the world."

Experts from Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have been consulted after local doctors were flummoxed by the extremely unusual condition.

They say she is suffering from a neurological syndrome called "spatial orientation phenomenon," Blic reports.

"They say my eyes see the images the right way up but my brain changes them," Danilovic said.

"But they don't really seem to know exactly how it happens, just that it does and where it happens in my brain.

"They told me they've seen the case histories of some people who write the way I see, but never someone quite like me."

There are a lot of questions I can't find answers to right now, but two things occurred to me.

"Spatial orientation phenomenon"

I don't give a damn if you are from Harvard or MIT, saying she has a neurological condition called "spatial orientation phenomenon" is a mind meltingly stupid thing to say. The label makes no sense and isn't even a thing, as far as I can tell, and it certainly doesn't explain anything. Besides, these experts apparently found nothing wrong with her brain, so whatever's going on is probably a bit more interesting. Also, there are no images involved in vision, so that's not the problem either.

Why does she have to turn some things upside down to use them?

You can make the world look upside down by wearing inverted prisms for extended periods (6-10 days). You start out a mess then regain pretty normal movement functions quite quickly (see this blog reporting a replication by Nico Troje and Dorita Chang of the classic version of this study). Recent work (Linden et al, 1999) has shown that, contrary to the original reports, the adapted visual experience does not revert to being the 'right' way up. So you can wander the world with everything seeming upside down and suffer no real problems.

The prism studies invert the whole visual field, and people learn to interact with things that are actually right side up but look upside down. They don't, as far as I know, have to turn individual bits of the world upside down in order to interact with it (e.g. this picture from the Troje project shows their participant sheet reading music that's the right way up in the world).

Danilovic has to turn a specific set of objects upside down. Nearly all the examples given have been about text; she reads and writes upside down and her computer monitor needs to be upside down. The other example is that she watches TV upside down. Why do those bits of the world need to be turned upside down? This is an interesting hint, I think.

As usual, I'm going to advocate that we start at the beginning, and consider the perceptual processes that underpin our typical view of the world. Let's see how far we can get with an analysis of information supporting this view before we start making up neurological syndromes or speculating about ventral vs dorsal stream processing on the basis that this sounds a bit like "perception" rather than "perception-for-action".

Calibration

How do we know where the things that we see in world are? Visual information contains no metric information; it is angular, so by itself it can only tell you the relative position of things. To interact with things, we need the metric details; how big, how far, etc? (Note: we don't want this information in centimetres; we want this information in action relevant units - how do I need to move my arm or shape my hand?).

The process of mapping a measurement onto a scale is called calibration. Think about your kitchen scales; they can tell you when you have 300gm of sugar because that amount of sugar changes the weight sensor in a particular way, and that particular change has been mapped onto the metric weight scale as corresponding to 300gm. In general, a given change in the weight sensor corresponds to a set change on the scale so if you zero your scale correctly, that set change can be read off as a weight.

Kitchen scales work without constant fiddling because that mapping is constant. In perception and action, that mapping, while fairly stable, is not constant. Every time you measure the world with visual perception, you are in a slightly different state; more or less tired, for example. You need the mapping to be expressed in currently relevant action units (because we perceive affordances) and so the mapping must be kept up to date and actively maintained via perceptual information.

The fact that this updating and maintenance is constantly happening is revealed by the numerous studies which demonstrate recalibration (including the prism adaptation studies described above). If you alter the relevant action units, people perceive the world differently, and this can occur over a surprisingly wide range. Geoff Bingham runs studies using VR where he has people visually perceive a location and reach to it; VR allows you to change that mapping any way you like and people happily reach to different locations given the same visual information and distorted visual or haptic calibration feedback (e.g. Mon-Williams & Bingham, 2007). There are plenty of more extreme examples (most notably the work of Henrik Ehrsson who uses rubber hands and video cameras to separate visual experience from your body entirely).

The mapping has a certain level of dynamic stability (we acquire preferred states over time and learning, and if I tune you up with feedback you will remain calibrated for a while, although this drifts quite quickly) and there are limits on what counts as a legitimate mapping, but in general we do what the information tells us to and map vision to action the way it tells us to.

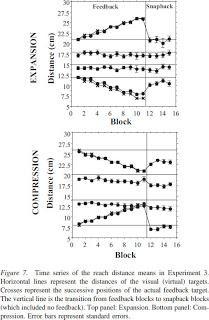

Interestingly, this is even true if the information tells you to do two different things about different parts of the space. Mon-Williams & Bingham (2007) had people reach to virtual objects at one of 4 distances. Over trials, the calibration feedback for the near object was moved in while the calibration information for the near object was moved out (or vice versa). People followed both objects (see Figure 1) demonstrating that calibration doesn't simply generalise across visual space.

Figure 1. People reached to objects as a function of the local calibration information, effectively expanding or compressing their reach space (Mon-Williams & Bingham, 2007)

So what is going on with Danilovic?

What are the key features to be explained? She experiences everything as upside down but this isn't a problem because this is a viable and stable calibration. Weirdly, however, certain parts of her visual field are perceived as the wrong way up relative to everything else and she cannot shake this effect. The examples of things which are upside down include anything to do with reading and writing, and watching TV. There are three questions: why is she miscalibrated, why can't she recalibrate to the right way round, and, most importantly, what defines the set of things that need to be rotated in the real world, and ?

1. Why is she miscalibrated?

This one, I have no idea. Once it happened, though, there are plenty of information based reasons why it stayed that way (see below).

2. Why can't she recalibrate to the 'right' way round?

The answer is in the flow of information. The prism studies tell us that you can alter the mapping between where things are in your visual field and what you do it interact with them quite happily, but that this adaptation does not lead you to experience the upside down world as the right way up (Linden et al, 1999). There is no 'correct' view of the world, there is only what the information tells you is there.Danilovic's visual system therefore has no reason to recalibrate. Her interactions with the world work (i.e. the 'upside down' mapping between her visual measurements and her actions is a perfectly viable one). This is the same reason why we don't recalibrate and come to see everything upside down; the calibration we have works. Even the discrepancy between the world in general and the set of things that have to be turned upside down isn't information that anything is wrong; the system is happy to have multiple calibrations, if that is supported by the information flow (Mon-Williams & Bingham, 2007). If I'm right, there is an informational basis supporting separating things like text from things like coffee cups, which allows the system to support multiple calibrations (see below).

So the answer is simply that her visual system has no information that anything is wrong, because, in a very important sense, nothing is.

3. What defines the set of things that have to rotated?

This is the weirdest part of the whole thing. Why isn't everything treated the same way? There must therefore be information that sets the things that must be rotated apart from the rest of the world (to enable the visual system to 'know' to treat these things differently), and there must be a reason why her inverted view isn't maintained by her interactions with those things.The examples are interacting with text, and watching TV. These are interesting cases, information wise. By Sabrina's taxonomy, information from text and TV is like linguistic information; you have to learn to Detect it, it's Specific to the source but it's About something other than the source, and you have to Learn to use it. It's also not Inherently meaningful, and it doesn't drive action via a Continuous coupling.

The most important bit, I think, is the Aboutness dimension::

- Information from text is created by the dynamics of an object with text on it interacting with light, but the meaning of that information is not that dynamic. The meaning is the conventional meaning of the text.

- Information from a TV screen is created by the dynamics of the light emitting elements of the screen, but the meaning of that information is not that dynamic; the meaning is the scene specified in the 2D projection of a 3D event taken from a specific point of view.

Any information that is About something other than the local dynamics is always paired with information about the local dynamics. For example, you can perceive both the contents of the picture and the fact that it is a picture. This fact, I think, is the thing that defines the set of things Danilovic will have to rotate; the set is 'anything that produces both lawful local information and conventional information'. Coffee cups only produce lawful perceptual information; text on that coffee cup produces lawful and conventional linguistic information. She should be able to reach for the cup successfully, but have to turn it upside down to read the text.

How does the system know it's in the presence of both (given they are fundamentally the same thing)? Learning, which, according to the ecological approach (E. J. Gibson, 1969) is a process of increasing differentiation of the flow of perceptual information. Just as you have to learn that the lawful information is about the local dynamics, you have to learn that for certain things, some of the information is actually about something else (e.g. text). Unlike the world, there is a 'right way up' for text (something extensively supported by the local language community) and once you have learned that text is About something other than the local dynamics, getting to that meaning is most readily done in the correct orientation. (People can learn to read and write upside down, but unless they do it exclusively it's hard to make it a preferred orientation.) TV is harder to make the case for, but the fact that it is a view from a specific point of view that doesn't flow correctly when you move identifies it as an image, albeit a moving one, and during learning you acquire the meaning of the image dynamics and not the of the pixel dynamics.

Science - how can we test all this further?

I have a few thoughts on this. The prediction is that she will need to rotate any surface that produces information that is About something other than the surface itself. Everything else should be upside down but otherwise fine.

- What, exactly, is in the set of things she has to rotate? This needs mapping out, to see whether my proposed category continues to make sense. What does she do with pictures; what about decent 3D VR (see the mirror discussion below).

- How normal is her reaching, walking, etc? It looks ok in the video but are there detectable problems?

- Is her prism adaptation during, say, reaching normal? My guess is yes; I don't think she has any problems recalibrating, based on the fact that she must be doing so in order to function over time in changing environments.

- Linden et al (1999) tested whether people's view of the world returned to 'upright' after prism adaptation using a shape-from-shading task (using information about how light and shade play on an object to judge shape; this is orientation specific). That would be a place to start, to test her visual experience.

- Mirrors - mirrors are weird, and kind of brilliantly fascinating. They are surfaces that produce information that specifies an exact replica of the visual information of whatever they reflect. They pretend to be something else (like TV or a picture) but they are really, really good at it, because other than a left-right reversal the optical structure behaves correctly as you move and explore. They are so good that people typically don't see the surface at all, and instead perceive the world specified by the flow in the mirror. You can see that they are a surface, though; so how does Danilovic interact with mirrors? How does this change as the presence of the surface becomes more or less obvious (clean vs half silvered mirror; small mirror with clear edges to large mirror taking up the whole visual scene)?

This is an utterly fascinating case and it's got some very weird aspects to it. I'd love to hear from anyone planning any research because it's a potential test bed for our ideas about information (especially Sabrina's taxonomy).

References

Gibson, E. J. (1969). Principles of Perceptual Learning & Development. Meredith Corporation, NY.

Linden, D., Kallenbach, U., Heinecke, A., Singer, W., & Goebel, R. (1999). The myth of upright vision. A psychophysical and functional imaging study of adaptation to inverting spectacles Perception, 28 (4), 469-481 DOI: 10.1068/p2820 Download

Mon-Williams, M., & Bingham, G. (2007). Calibrating reach distance to visual targets. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 33 (3), 645-656 DOI: 10.1037/0096-1523.33.3.645 Download