Part of the problem is that I’ve never been fortunate enough to learn Chinese. You see, scholars of religion are often insistent on reading scriptures in their original languages. It has been a long time since I’ve picked up the Daodejing, one of the formative scriptures of Daoism, and I was struck by a number of things. First (and I have the confirmation of Sinologists on this), the Daodejing is difficult to understand. This isn’t just a translation issue. Nor is it an issue of Chinese thinking. All world scriptures are difficult to understand. One of the major problems with the Bible is that it has been translated into English for so long that many assume the language concerns are negligible. They’re not. The Bible has many obscure parts. Also it’s worth noting that the Daodejing has been translated nearly as much as, if not more than, the Bible. It is a very influential text, in part, I’m sure, because it’s not easy to understand.

Part of the problem is that I’ve never been fortunate enough to learn Chinese. You see, scholars of religion are often insistent on reading scriptures in their original languages. It has been a long time since I’ve picked up the Daodejing, one of the formative scriptures of Daoism, and I was struck by a number of things. First (and I have the confirmation of Sinologists on this), the Daodejing is difficult to understand. This isn’t just a translation issue. Nor is it an issue of Chinese thinking. All world scriptures are difficult to understand. One of the major problems with the Bible is that it has been translated into English for so long that many assume the language concerns are negligible. They’re not. The Bible has many obscure parts. Also it’s worth noting that the Daodejing has been translated nearly as much as, if not more than, the Bible. It is a very influential text, in part, I’m sure, because it’s not easy to understand.

Paradox isn’t within the comfort zone of many western religions. We like our belief structure to be (mostly) rational and believable. In fact, to start an argument just point out the fact that the Bible has contractions. (It does, for the record.) The point being that a westerner will want to believe it is consistent and coherent throughout. If they can’t have that in English then they’ll say it’s inerrant in the original languages (it’s not). Religions shouldn’t make your brain hurt. Paradoxes, however, require deep thought. They can’t be read quickly to be stored away as factual information. They do, however, constitute a large part of life. Look at Washington and meditate. Daoism, the religion that generally follows the teachings of Lao Tzu (the putative author of the Daodejing), finds truth in contemplating opposites which are both simultaneously true. And not true. Interestingly, many of the sayings in the Daodejing are similar to ideas attributed to Jesus in the New Testament.

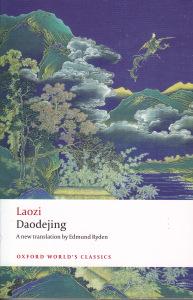

Dao is often translated “way.” One of the striking things about Edmund Ryden’s translation is his choice to use the feminine pronoun for “the way.” This is motivated, as I read it, out of concern to do justice to the presentation of the dao in the Daodejing itself. While the dao is not god, nor personal, it is powerful. The recognition of feminine power is clear in many aspects of the Daodejing. That’s not to say that the culture wasn’t patriarchal, but merely that it recognized balance—the famous yin and yang—as being inherent in the way the universe works. If such an idea could truly take hold the world might be a better place even today.