Book Review by George S: The Turmoil is the first in Booth Tarkington’s ‘Change’ trilogy. The three books are not connected by common characters, but by their theme – the industrialisation and transformation of a mid-Western town (based on Indianapolis, where Tarkington was raised} in the years between the 1870 and 1920.

The Turmoil is centred on the Sheridan family – who have new money and driving ambition. The next book in the trilogy, The Magnificent Ambersons is about the decline of one of the old families whose traditional importance is over-shadowed by the new breed of entrepreneurs. The third book, The Midlander (also known as National Avenue ) is about the contrasting destinies of two brothers in this time of social change.

The Turmoil is set at the start of the twentieth century, /the city is booming, and Mr Sheridan is ‘the city incarnate’:

The Sheridan Building was the biggest skyscraper; the Sheridan Trust Company was the biggest of its kind, and Sheridan himself had been the biggest builder and breaker and truster and buster under the smoke.

Cover of the American first edition.

Cover of the American first edition.

The black sooty smoke industrialisation is the novel’s central symbol. It gets everywhere and smudges everything, but it also represents the triumph of industry and capitalism. Mr Sheidan loves it:

[W]hen soot fell upon his cuff he chuckled; he could have kissed it. “It’s good! It’s good!” he said, and smacked his lips in gusto. “Good, clean soot; it’s our life-blood, God bless it!” The smoke was one of his great enthusiasms; he laughed at a committee of plaintive housewives who called to beg his aid against it. “Smoke’s what brings your husbands’ money home on Saturday night,” he told them, jovially.

The soot in this novel reminds me of the fog in Bleak House – it gets everywhere. Dickens, I suspect, is Tarkington’s model as a novelist, not only in way he uses the soot, and in his clear, very visual and distinct depictions of character, but from time to time also in his play with language and simile:

“Altogether, the town here was like a boarding-house hash the Sunday after Thanksgiving; the old ingredients were discernible.”

Dickensian, too is his ambivalent description of the sheer energy of progress. This paragraph about the coming of noise and chaos reminded me of the passage in Dombey and Son about the building of a railroad through Staggs’s gardens, once a sociable neighbourhood:

“Trolley-cars and long interurban cars, built to split the wind like torpedo-boats, clanged and shrieked their way round swarming corners; motor-cars of every kind and shape known to man babbled frightful warnings and frantic demands; hospital ambulances clamored wildly for passage; steam-whistles signaled the swinging of titanic tentacle and claw; riveters rattled like machine-guns; the ground shook to the thunder of gigantic trucks; and the conglomerate sound of it all was the sound of earthquake playing accompaniments for battle and sudden death. On one of the new steel buildings no work was being done that afternoon. The building had killed a man in the morning—and the steel-workers always stop for the day when that “happens.””

Tarkington has a fair amount of the Dickensian vitality, but he lacks Dickens’s social range, and his range of sympathies. The trilogy rarely ventures outside the world of the higher social orders; there is little interest in the life of the working man, and even less in the life of those he tends to call ‘darkies’.

The plot of The Turmoil is simple enough for a folk tale. There was a rich man and he had three sons. The two elder sons are dutiful in following their father in pursuit of wealth; the third one, Bibbs, is a dreamer, often dismissed useless, even as an idiot. True to the folk-tale pattern, it will be the third son who triumphs.

Sheridan is the capitalist Will incarnate; he bullies the world until he gets what he wants.He bullies his younger son to enter his business at the bottom and learn the hard way, when all Bubbs wants to do is write poetry and essays. We are given some examples of his writing – light charming essays that are the opposite of his father’ s stern practicality. When Bibbs changes (thanks to his love for a good woman) and embraces the capitalist lifestyle, he burns all the essays and poems that now seem worthless to him. From what I can gather, Tarkington’s own earlier writings tended towards the belles-lettristic. Is Bibbs’s destruction of his trivial writing a declaration on Tarkington’s part that he too is now dedicated to more serious things?

Also contrasted with the Sheridans are the Vertrees family – who pride themselves on having been one of the old rich families of the city; they are still at the center of the city’s social life, but now their importance is dwindling, as is their income, based as it is on investments, not on enterprise. Tarkington describes their slow decline, as they look on the future despairingly. Only one member of the family has the gumption to do anything about it. Mary, the daughter, makes the rational decision to charm the Sheridans, and to marry money for the sake of her family. She throws herself at Jim, the insensitive older son, though she can’t help being fascinated by Bibbs, the obviously more sensitive and intelligent younger one.

Mary is a lively character at the start of the book, but becomes less so as she develops a sense of high-minded morality. Her parents are rather sketchily shown. Tarkington would depict the pride and decline of an old family in more detail in the nest volume, The Magnificent Ambersons.

Having set up Sheridan as an unstoppable force of nature, Tarkington challenges him with disasters. His two older sons James gets poetic justice whan a building he has jerry-built in a hurry collapses on top of him. The second son collapses under the strain of work and a bad marriage.

Sheridan wants to bully Bibbs into the family business, but Bibbs resists until he and Mary fall in love. The story then becomes less credible, as Bibbs proves himself a business genius and earns his father’s respect.

The second half of the novel becomes increasingly sentimental, with Bibbs and Mary becoming increasingly high-minded and self-sacrificing as they face challenges and disasters.

But still – I enjoyed the book enough to read the two others in the trilogy.

A press advertisement for the first British edition shows the book marketed as a love story.

A press advertisement for the first British edition shows the book marketed as a love story.

The Magnificent Ambersons takes as its anti-hero another character of indomitable will, George, the young scion of the Amberson family, who assumes that social eminence is his due, because of his family. The novel traces his career from his arrogant childhood (when locals dream that he will get his ‘comeuppance’ one day) to an adult life when he is disdainful of the idea that he should have anything as vulgar as a profession. When the family money vanishes, he is brought low. I watched the Orson Welles film recently, and was surprised to see how closely it sticks to the pattern, and even the dialogue, of the book (though there are gaps where Welles’s original long slow movie was butchered by the studio who thought it would have more public appeal with an hour chopped out of it.

The hero of The Midlander is almost the opposite of George, although he has an equally fierce single-mindedness. As the book’s title suggests, he is the embodiment of the mid-west; he is full of pioneering spirit, with huge dreams for improving his city. He is good natured and generous, but ruins his life by marrying a pretty girl from New York with no sympathy for his home city, for his ambitions, or for the romance of the entrepreneurial spirit. Of the three novels, this is the one I enjoyed most – perhaps because its ending was the least predictable.

All three novels explore one of the most interesting times in American history, when it was transformed by industrialisation, mass immigration and the coming of the motor-car.

Tarkington wants to show us how that process worked, and to make us aware of the winners and losers of the period. A passage from The Midlander explains what he wants us to understand (And it uses the new medium of the cinema to explain it – a medium that would find uses for many of Tarkington’s books from the twenties to the forties.)

Cameras of the new age sometimes record upon strips of moving film the slow life of a plant from the seed to the blossoming of its flower; and then there is thrown upon the screen a picture in which time is so quickened that the plant is seen in the very motions of its growth, twisting itself out of the ground and stretching and swelling to its maturity, all within a few minutes. So might a film record be made of the new growth bringing to full life a quiet and elderly midland town; but the picture would be dumbfounding. Cyclone, earthquake, and miracle would seem to stalk hand-in-hand upon the screen; thunder and avalanche should play in the orchestra pit. In such a picture, block after block of heavy old mansions would be seen to topple; row on row of stout buildings would vanish almost simultaneously; families would be shown in flight, carrying away their goods with them from houses about to crumble; miles of tall trees would be uprooted; the earth would gape, opening in great holes and long chasms — the very streets would unskin themselves and twist in agony; every landmark would fly dispersed in powder upon the wind, and all old-established things disappear.

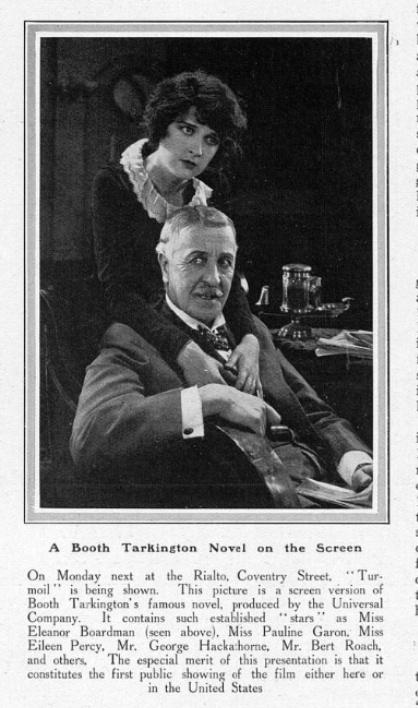

The Turmoil was filmed in 1924: