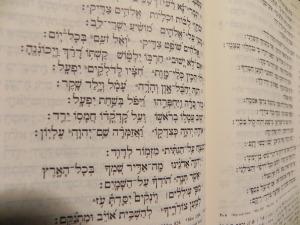

The Bible has a way of defining lives. I realized this at a young age, and although my experience was limited to what life reveals in a small town. Still it was evident that people even there traced trajectories defined by Holy Writ. I used to ask my students that if something effected you every day, in ways both massive and subtle, and was potentially dangerous, wouldn’t you want to know about it? Religion in general, and the Bible in particular, fit this description. As the road began to fork at the usual junctures of my life (high school, college, whatever comes after college), the Bible played a role. For some reason the Hebrew Bible captured my attention more than the Christian scriptures—perhaps it was because there was more narrative in the “older testament,” and more puzzles to be solved. While the New Testament seemed to be definitive for matters of doctrinal importance, the Hebrew Bible retained a sense of mystery and intrigue. Many of its characters, although ending up as “good guys” have decidedly questionable episodes in their pasts. What’s not to like?

Ironically, however, I discovered a job market where someone from a Christian background was immediately suspected of a supersessionist outlook on the Hebrew Bible. Why would a Christian have any interest in that, if not for fabricating prophecies? Many Jewish scholars were focusing on biblical studies from “both” testaments, and my puerile interests were suddenly naive and not worthy of attention. This dynamic has always interested me: what right does an outsider have to speak with any kind of authority about another peoples’ culture or belief? You’d think in higher education we might be beyond such parochialism, but instead, this may be the very definition of its hotbed. What does it take to gain scholarly credibility? Being a “white” male in a pluralizing society certainly doesn’t help.

Books are like companions on life’s journey. My reading life started with the Bible and soon gained hundreds of other companions on that long, difficult path to a doctorate in biblical studies that defined an ill-fated career. I cannot reckon the number of books I’ve read along the way, hundreds of thousands of weary pages. And now I find myself back among the biblical crowd, from the outside looking in. They speak authoritatively, I merely whimper. Whether you see it or not, the Bible is here on the streets of Manhattan. Proclaimed or ignored, invisible or plainly manifest. And those of us who’ve spent a lifetime with it have nothing considered worthwhile to say. Once the Bible take a hold, the trajectory for life is set.