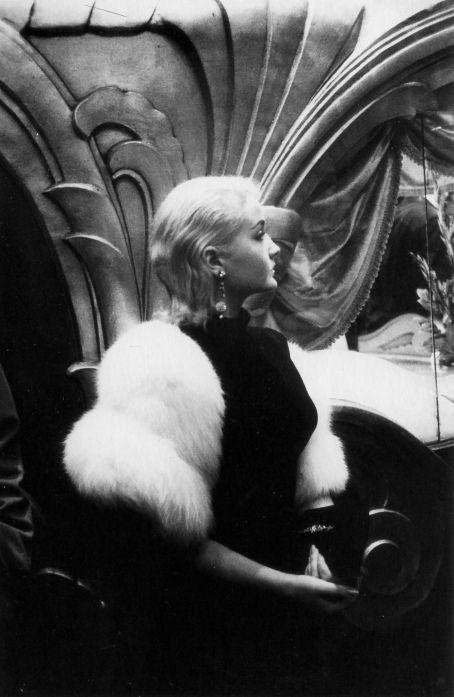

About twenty years ago, Sharon Collins was visiting San Francisco's Museum of Modern Art, located in the city's bustling downtown district. She was browsing the photography exhibits when she found herself drawn to a particular image. The black and white photo, pictured directly below, was of a young girl with an unreadable expression working as an elevator operator. "I stood in front of this particular photograph for probably a full five minutes, not knowing why I was staring at it," Collins told NPR in an interview. "And then it dawned on me that the girl in the photo was me."

The photo is one of the most iconic images of the 20th century. At the time it was taken, Collins was a fifteen-year-old working a summer job at Miami's Sherry Frontenac Hotel. She was accustomed to having tourists snap photos of her, but she doesn't remember this particular photographer. For years, she didn't even know of the image's existence, let alone the buzz that surrounded it. Beat bard Jack Kerouac wrote of it: "That little ole lonely elevator girl looking up, sighing in an elevator full of blurred demons, what's her name & address?" From the photo, Kerouac guessed that the girl was lonely. Collins thinks he was pretty close. "It's not necessarily loneliness, it's ... dreaminess," she said.

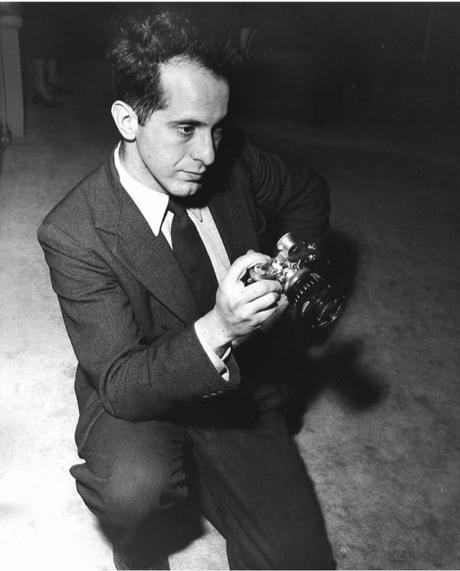

The photographer, as some readers may know, was Robert Frank, who died earlier this month in a hospital near his remote home in Mabou, Nova Scotia. In 1947, shortly after the end of the Second World War, Frank left what he described as the small-mindedness of his hometown in search of adventure. At just 22 years old, he arrived on his own in New York City. Eight years later, having secured a letter of recommendation from Walker Evans, he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. He used that money to travel across the United States, taking three road trips with his wife and two young children in tow, and snapping some 28,000 photos of Americans. A mere 83 of those images were published in the landmark book The Americans.

The Americans is a cross between Jack Kerouac's On the Road and Alexis de Tocqueville's Democracy in America. It's an unflinching view of America through the eyes of an outsider. Unlike other documentary photographers before him, such as Dorothea Lange or Russell Lee, Frank wasn't trying to be completely objective (although, as Howard Zinn notes, all history is biased by virtue of how you choose to document). Instead, Frank recorded not only what life was like in his newly adopted home, but also his reactions it. In this way, his photography is like Postimpressionism - the French art movement that was less hung up on naturalistic depictions of reality and more concerned with abstract qualities. ( Van Gogh's Starry Nights, for example, is not so much about what a starry night sky looks like, but how Van Gogh felt while looking at one).

First, a bit of about Frank: the Jewish-Swiss photographer was born in Zurich, Switzerland in 1924, just shortly after his German-born father, Hermann Frank, settled in the city with his wife, Rosa. His father, however, became stateless in 1935 when the Nazis institutionalized their racist ideology in what became known as the Nuremberg Laws. The laws deprived German Jews of their rights of citizenship, giving them the status of "subjects" in Hitler's Reich. They also forbade marriage and sexual relations between Jews and those of "German blood."

Since Frank's family was living in neutral Switzerland, they were spared from the horrors of the Holocaust. But the experience of seeing the brutality of Nazism, racism, and fascism in the international news shaped how Frank understood oppression. "I photographed people who were held back, who never could step over a certain line," the photographer later told The Times. "My mother asked me, 'Why do you always take pictures of poor people?' It wasn't true, but my sympathies were with people who struggled. There was also my mistrust of people who made the rules."

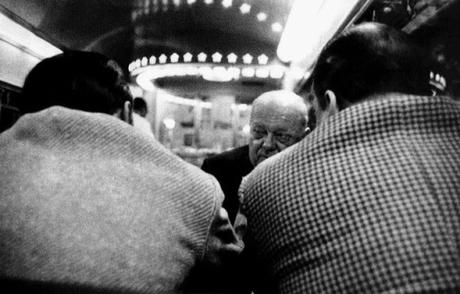

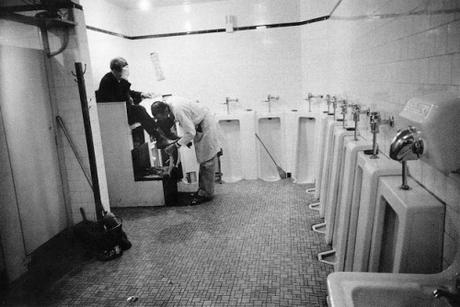

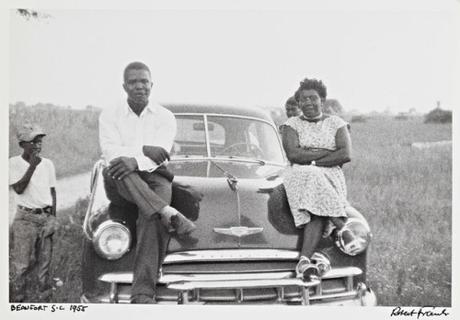

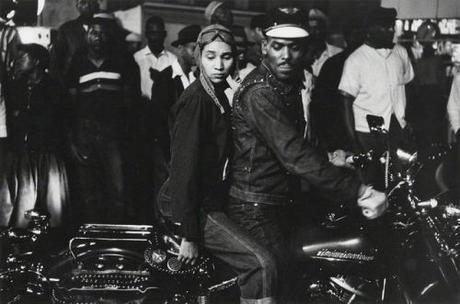

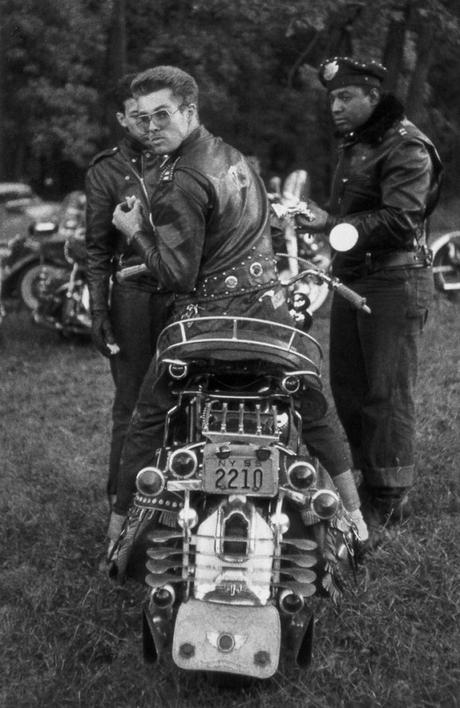

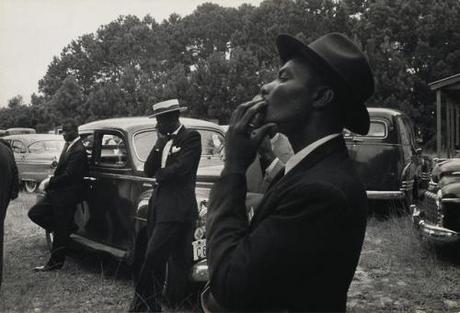

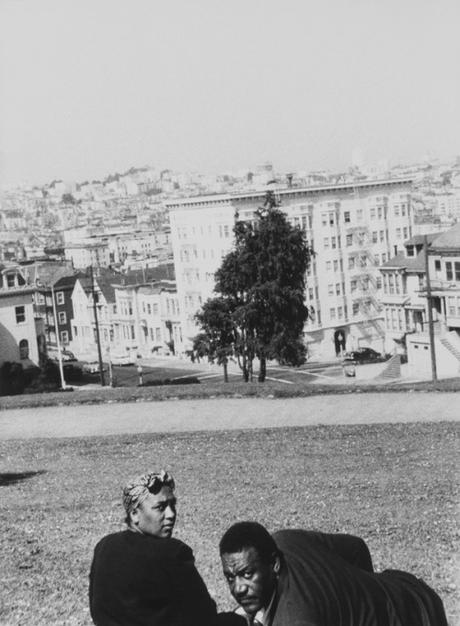

It's no surprise, then, that when Frank set off to photograph America, he sought out the hidden places and unknowable faces that made up the country's story. He photographed gas stations, drug stores, auto factories, luncheonettes, and roadside bars. He documented drifters, trans people, harassed mothers, groping teenagers, and poor blacks in the segregated South. The trips were not without incident. He spent three days in an Arkansas jail on the accusation of being a communist spy during the Cold War. While there, he spotted a frightened, young black girl looking up at him from a jail cell, which he said is the missing photo in The Americans. Posthumously, The New York Times wrote of his work:

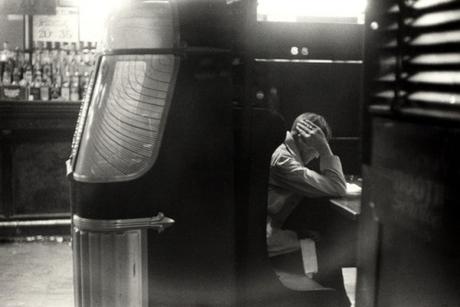

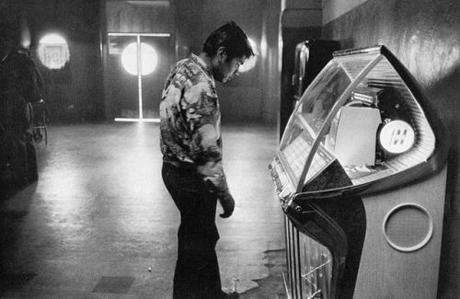

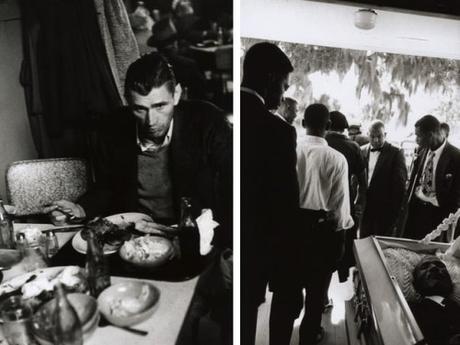

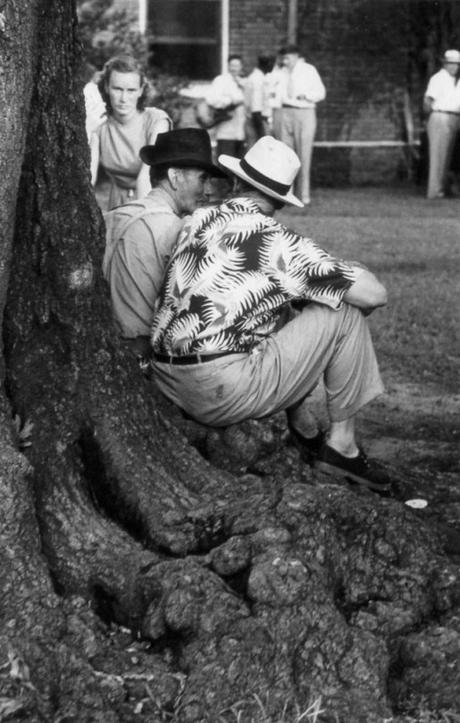

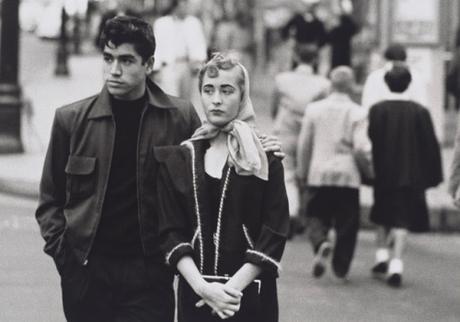

Frank hoped to express the emotional rhythms of the United States, to portray underlying realities and misgivings - how it felt to be wealthy, to be poor, to be in love, to be alone, to be young or old, to be black or white, to live along a country road or to walk a crowded sidewalk, to be overworked or sleeping in parks, to be a swaggering Southern couple or to be young and gay in New York, to be politicking or at prayer. [...] He wanted to find the men and women others would consider unremarkable, as well as the symbols and objects that defined them. Falling into a place-to-place rhythm, he took pictures of bystanders, vagrants, newlyweds, Christian crosses, jukeboxes, mailboxes, coffins, televisions, many cars, and those many flags.

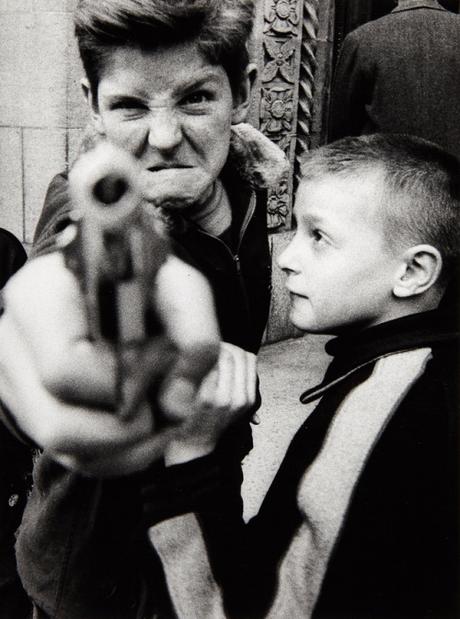

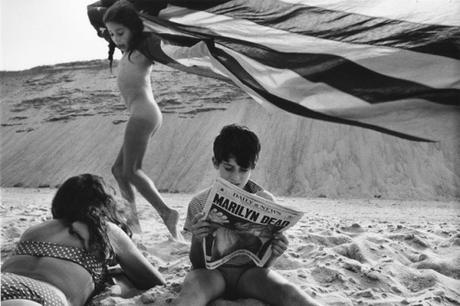

Oh, those flags. One of the best images from The Americans can be seen at the top of this post. On a trip to upstate New York, Frank attended a Fourth of July celebration. There, he photographed two little girls wearing pristine white dresses while skipping underneath a diaphanous American flag. On closer inspection, you can see the flag has a small tear, and the lawn is littered. In the lefthand corner of the photo, there's the only visible expression: a sneering boy.

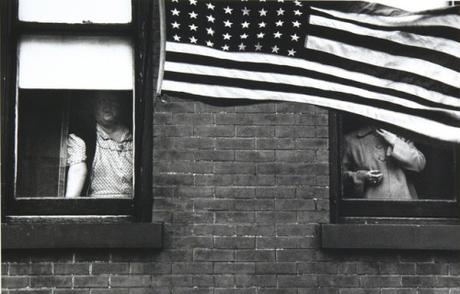

The fact that the flag is slightly transparent is a symbol of what it means when you turn the book's page, which is where you'll see Frank's most famous image - that of a racially segregated New Orleans trolly (pictured above). Using the window supports as ready-made partitions, Frank showed the most evident dividing line in American society. A sour-looking woman sits near the front, two privileged looking children behind her, and the weary Black man is consigned to the back. The watery, ghost-like reflections at the top of the streetcar give the image cinematic elan, as well as poignancy.

American critics despised the book when it first came out. For one, Frank's experimentation with composition, blur, and grain was at odds with the photography world's dominant aesthetic, which favored technical perfection and clean lines. But more than that, his work was characterized as anti-American. Minor White, the acclaimed photographer and Aperture magazine editor, described The Americans as "a wart-covered picture of America by a joyless man who hates the country of his adoption." Popular Photography characterized it as "a sad poem by a very sick person" and dismissed the images as "meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons, and general sloppiness." Others described the pictures as "warped" and "hateful."

As cultural critic Janet Malcolm would later explain, the problem was that "no one had ever made pictures like that before." In the closing decade of America's Leave It To Beaver narrative, Frank's unvarnished view defied the country's self-image. "The Swiss-born photographer's grainy, cock-eyed, prowling pictures of tattered flags and ghostly glowing jukeboxes, festering racial injustices and the sad lineup of lost souls who had seen their tethers to the American Dream unceremoniously cut" didn't measure up to the picture-perfect story Americans told about themselves and their heritage. Yet, if one looks a little closer, at the core of his social criticism is the romantic ideal of finding and honoring American values. Those values are captured in the single most enduring phrase from the American Revolution, that all men are born equal and free.

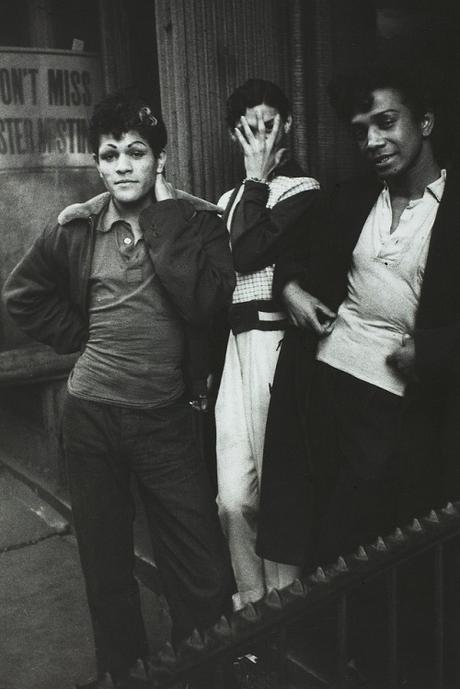

"Patriotism, optimism, and scrubbed suburban living were the rule of the day," Charlie LeDuff wrote in Vanity Fair in 2008. "Myth was important then. And along comes Robert Frank, the hairy homunculus, the European Jew with his 35mm Leica, taking snaps of old angry white men, young angry black men, severe disapproving southern ladies, Indians in saloons, he/shes in New York alleyways, alienation on the assembly line, segregation south of the Mason-Dixon line, bitterness, dissipation, discontent."

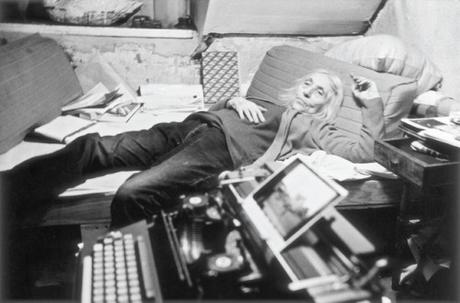

Twenty years later, writing in The New York Times, Gene Thorton said the book ranked "with Alexis de Tocqueville's Democracy in America and Henry James' The American Scene as one of the definitive statements of what this country is about." Kerouac wrote in the book's introduction: "That crazy feeling in America when the sun is hot on the streets and music comes out of the jukebox or from a nearby funeral, that's what Robert Frank has captured in tremendous photographs taken as he traveled on the road around practically forty-eight states in an old used car ..."

When Frank passed away earlier this month, I slid my copy of The Americans off my bookshelf, dusted it off, and revisited the images. I hadn't opened this book in over a decade. I first saw it as a young man in my early 20s while hanging out with a friend who's a talented photographer. "Here, you'll like this," he said. Even though I knew very little about photography at the time, I could feel the book was important. Frank's visually raw and expressive style was somehow devoid of sentimentality, but at the same time, supremely sentimental. His seemingly loose, casual "snapshot" compositions were rough, off-kilter, and grainy, like television news transmissions from the same period. They felt, in a word, real.

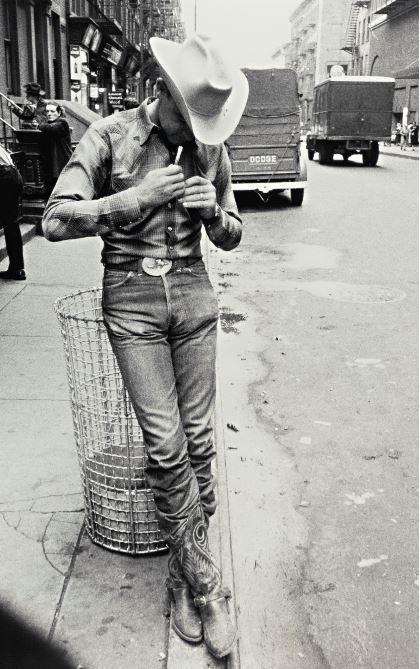

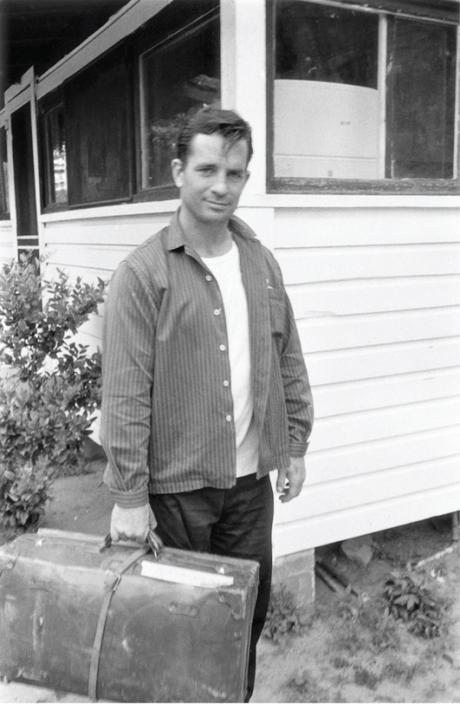

While revisiting The Americans, I was struck by what has and hasn't changed in America. I was also stunned by how stylish everyone looked - not just because Frank was a talented photographer, but because the outfits genuinely looked good. The crossdressers in androgynous clothes, sporting sherpa bomber jackets, polo shirts, and wide-legged jeans. The cowboy pausing to roll a cigarette in midtown Manhattan while ducking under his hat. The older men in heavy covert twills and Shetland tweeds. There's a heavy dose of workwear, too: the women in leather jackets and buffalo plaid flannels, as well as the men in rancher jackets and ball caps. The photo of Kerouac, taken in front of his mother's home, shows the writer in an outfit that could have been lifted from a Levi's Vintage Clothing lookbook. Kerouac is shown holding his strapped leather luggage while wearing a white tee with baggy chinos and a button-front overshirt. A notepad and pen peek out from his chest pocket.

The Americans defies not only American mythology but also the grand narrative about how people used to dress. In popular menswear lore, there's a familiar romanticizing of the world as it is imagined to have existed before fashion got to it. Tailors and cordwainers once lovingly handcrafted clothes, one-by-one, for discerning customers. Everyone wore three-piece suits and an apple pie sat cooling on every windowsill. Moreover, men still held to the Jeffersonian ideal of a gentleman farmer, except the only crop they cultivated was that of exceptional taste and manners.

You see this in popular reactions to , the 1965 book published nearly a decade after Frank shot his images. Ivy Style aficionados like to use the book as a marker in history to show how far we've fallen from grace. But, as David Marx notes in his book , Take Ivy was more about marketing than anthropology. "The photographer and filmmaker were under direction from Kurosu and Shosuke Ishizu of VAN Jacket," says David. "The VAN team asked them to shoot students who fit their preconception of what constitutes 'Ivy League,' especially its more refined and dressed-up side. The whole point of Take Ivy was to sell an older style Ivy League clothes, such as three-button-stance suits. Most people in the book, however, are very casually dressed, so they could only fake it so much."

What a striking difference, then, to see Frank's photos, which show not only a broader cross-section of American society, but also a range of people in casual attire. To be sure, tailored clothing has been on a steady decline since the 1950s. But Frank shot ordinary Americans as they actually dressed - and how they did it so well. The outfits aren't pitch-perfect or even expensive. But they're stylish in the way that counts the most: they tell a story about people. At its best, clothing is the first level, the surface level, for a deeper understanding of human complication.

A few weeks ago, I met Avery Trufelman, a producer at 99% Invisible and the host of the wonderful clothing podcast series Articles of Interest. In the Bay Area, where you're likely to see a ton of athleisure and sloppy t-shirts, she asked if I'm continually disappointed with the city's fashion landscape. Cities have indeed gotten uglier in some ways. Business causal remains a scourge and men as a whole could put in more effort. But if you take a moment to look, you'll see no shortage of stylish people. On a day to day basis, I see punks, skaters, hippies, outdoorsy people, older men in beautifully tailored clothing, inveterate thrifters, musicians, artists, and counter-cultural types. Style is more nuanced and diverse today, but a lot of what Frank saw in everyday Americans in the 1950s is still evident and surrounds us.