Creating a complex for 8,000 people, 30 metres underground, in the middle of the war was no mean feat. Sections of the tunnels are lined in cast iron, and marks show the companies for whom these panels were originally made. Some bear the initials LER, for London Electric Railway - a company which had ceased to exist when the Underground system was unified in 1933, so they had obviously been found in storage somewhere.

The two parallel tunnels were each divided horizontally into upper and lower levels, mostly dedicated to bunk bedding (although other facilities included a medical centre, recreation room, a buffet serving tea, sandwiches and cakes, and bathrooms). Triple layers of bunks were crammed into the tunnels, each set of six separated from the next 'room' by a thin divider. Red-painted ventilation ducts sat between the bunks. With no natural air or light, trains rattling close overhead, music until lights out, and the sound of conversations, crying babies and snoring adults, it must have been an extraordinarily difficult place to get some sleep! Unsurprisingly, the deep-level shelters were never filled to more than one-third capacity.

Yet after the war, the tunnels would come into use as accommodation again. While smaller numbers of residents, no fear of devastation above, and the knowledge that this was only 'home' for a few nights must have made it more palatable, Clapham South still seems a strange and unappealing option.

So who stayed here? Among the most significant guests were 230 of the passengers on the MV Empire Windrush who arrived in London in 1948. Answering an appeal to emigrate from the Caribbean to fill essential jobs in Britain, it's hard to imagine how they must have felt to find that their first accommodation here was a repurposed air raid shelter 180 steps below ground. One described it as a 'sparsely-furnished rabbit warren'. Even given the housing shortages in post-war London, the choice of this venue is indicative of the ambiguous-to-hostile welcome they received. Leaving by day to go to the nearest labor exchange in Coldharbour Lane, many soon found new homes in the Brixton area; none stayed in the shelter for longer than three weeks.

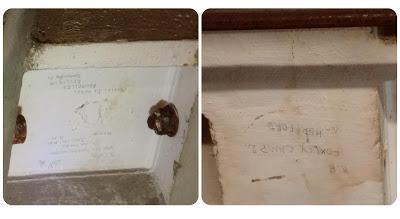

Many of the Windrush men were ex-servicemen, so somewhat bleak and utilitarian accommodation was perhaps not a novelty. The same may have been true of the armed forces personnel who stayed here, both in 1945 after it closed to the public in May and immediately reopened as a military leave hostel, and during George VI's funeral in 1952. They were bored enough to graffiti the walls as they lay in their bunks; since they were lying in bed as they wrote, the graffiti are of course upside down.

However, a more ambitious use of the tunnel came in 1951 when it was rebranded the Festival Hotel, a budget option for Festival of Britain visitors, especially groups. Bed and breakfast was three shillings a night. For their money, guests got a bunk with blankets (women also got a sheet), cold water to wash in, canteens, and a first-aid room. A South London Press report described the experience:

Deputy manageress Mrs Florence Davison deals with incredible brusqueness and efficiency with all comers and with ubiquitous eyes sees to it that those down from the tube do not miss the cash desk and their 3s. contribution for the night. ... Those staying the night are not encouraged to put in an appearance before 8.30pm at night and by midnight the air is filled with the whistle of mass snoring, the creaking of beds and an occasional cough. But after 6am there is no peace. Tube trains rumble across the ceiling, armies of people walk the corridor overhead. ... The 1,500 Festival visitors climb up the 192 steps to air and sunshine, or wait for the lift, six at a time.Even with a few more lavish touches like white tablecloths on the buffet tables, one suspects that they were rather taken aback at the 'hotel'! There seems to have been a determination to enjoy the experience nonetheless: French student Bernard Masson later recalled, 'It was very, very, very primitive ... The bunks were quite stiff, but in fact, we didn't mind too much because we were all excited to be in a foreign country.' The venture was clearly successful enough to bear repeating: the shelter again provided accommodation for visitors (and troops) during the 1953 Coronation.

The shelters were not used for accommodation after that. Instead Clapham South and most of the others stayed empty until they were later used for secure document storage. Belsize Park had been first in 1977, with Clapham South following in the mid-80s: its bunks were back in use, now holding storage boxes. However, about a decade ago the company's lease was not renewed and the shelter became empty once more.

Traces of these past uses are scattered throughout the shelter: a sink from the medical room, the buffet fuse box, shadows on the wall where urinals once were. Shelves hold archive boxes - there for illustrative purposes, not forgotten originals! Taking us full circle, these fragments from the shelter's beginnings are also key to its current use: as a venue for historical tours, part of the London Transport Museum's Hidden London series.