How far should free speech go?

Floyd Abrams is the country’s leading First Amendment lawyer. I bought his book, The Soul of the First Amendment, at the recent symposium on the post-truth culture (mainly for the opportunity to shake his hand).

Freedom of speech in America is enshrined by the First Amendment — “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech or of the press . . . .” (The Fourteenth Amendment made it applicable against state governments too.) A key point of the book is how unique this actually is, not only in history, but in today’s world. In fact, no other country so exalts the inviolability of free speech. All others subject it varying restrictions. And mostly they involve what are basically political concerns — the very sphere wherein freedom of expression is actually the most consequential.

People have been jailed in Europe for the crime of Holocaust denial. That is, advocating a certain interpretation of history. Europe also has many laws against “hate speech,” quite broadly (if vaguely) defined. Abrams cites a Belgian member of parliament prosecuted for distributing leaflets calling for a “Belgians and European First” policy, sending asylum seekers home, and opposing “Islamification.”

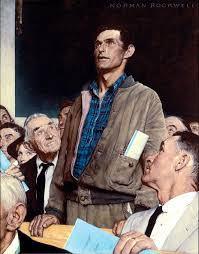

America is a free speech paradise in comparison not only to such other places, but to our own past. The First Amendment actually played almost no role in our law and culture until around the mid-20th century. Abrams cites a 1907 Colorado episode. A lame-duck governor, defeated for re-election, exploited a newly passed law to pack the state supreme court with judges who thereupon ruled that he’d actually won the election. A newspaper published an editorial criticizing this ruling. The Colorado court held the editor in contempt. And that was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court, in an opinion written by the famed Oliver Wendell Holmes.

The idea underlying all these cases is that rights are never absolute, being always subject to a balancing against the public interest.

Abrams argues, however, that the First Amendment’s language, absolute on its face, reflects its authors having already performed such a balancing. The benefits to society, to the kind of polity they aspired to create, of unfettered freedom of expression were balanced against what public good might otherwise be promoted. And in that balancing, freedom of expression won out, being found the weightier. It’s more important to have a society with such freedom than, for example, one where religious sensibilities are protected from insult — or where judges are shielded from editorial criticism. That’s why we have the First Amendment, and why it actually does not permit the kind of balancing underlying that 1907 Colorado case. Justice Holmes himself came to repent his decision there, dissenting in similar future cases, and eventually the Court overturned its Colorado ruling.*

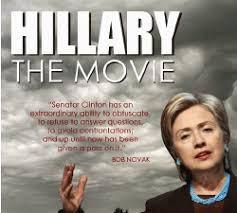

The exact same considerations were central to a case Abrams argued before the Supreme Court, which he discusses. He there contended that the government, because of the First Amendment, may not criminalize distribution of a film critical of a presidential candidate. (I quoted Abrams about it on this blog.) He won the case. And given our common understanding of free speech in America, that might seem a no-brainer.

Abrams cites here a case in which Nike was accused of corporate misdeeds and sought to rebut the charges with press releases and publications. For that, the company was sued in California state court under a consumer protection law barring false advertising and the like. The real issue was whether the First Amendment protects Nike’s freedom of speech. When the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, the New York Times submitted a brief which Abrams quotes: “businesses and their representatives have just as much a right to speak out on any public issue as do interest groups and politicians . . . .” And because issues concerning businesses “are increasingly fundamental to the world’s social and political landscape, the withdrawal of corporate voices on those issues from the media would deprive the public of vital information.” Abrams deems the newspaper’s stance there starkly at odds with the position it later took on Citizens United, where the issue was really the same. Issue advocacy, and backing candidates for office, stand on identical ground as far as the First Amendment is concerned.

For me personally, all this is not abstract, but essential to my being. Abrams discusses the landmark case of Times v. Sullivan, which particularly protects criticism of public officials. That saved my butt in 1973 when I was sued for millions by guys whose misconduct I mentioned in a book on local politics. I love the freedom to express myself like that, and in this blog.

Abrams notes Europe’s “right to be forgotten,” with search engines being required to erase true information about people when requested, such as reports on criminal convictions. I blogged about this in 2009 (again quoting Abrams), when two convicted German murderers, Wolfgang Werle and Manfred Lauber, sued to erase their names from Wikipedia. In defiance of that affront to freedom of information, I made a point of putting their names in my blog post, and do so again here. God bless America and the First Amendment!

* Yet even this right isn’t actually absolute. The First Amendment doesn’t protect libel or slander, child pornography, or shouting “fire!” in a crowded theater (as the same Justice Holmes famously explained).

Advertisements &b; &b;