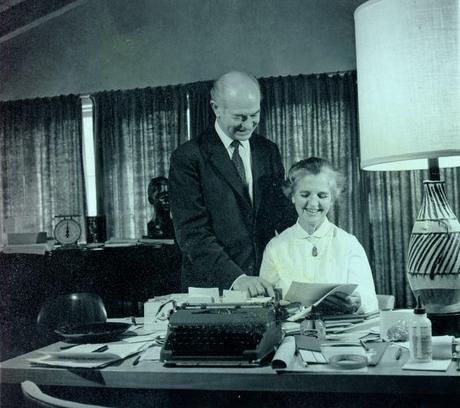

Linus and Ava Helen Pauling working on “An Appeal by American Scientists to the Government and Peoples of the World”. 1957.

Creative Nonfiction by Melinda Gormley and Melissae Fellet.

St. Louis, March 15, 1957

Sun streamed in through a stained glass window of the chapel at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri on a pleasant and sunny Wednesday afternoon in mid-May 1957. About 1,000 people listened to Linus Pauling, the 1954 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, deliver a fiery speech urging an end to nuclear weapons testing. The years of political activities were taking their toll on 56-year-old Pauling. His white hair was thinning and deep wrinkles lined his forehead, yet he still dressed smartly in a suit and tie.

“If you explode a bomb in the upper atmosphere, you can’t control it,” Pauling explained to the rapt crowd. “The fallout radiation, Strontium-90, and similar things, spread over the world, drop down,” he noted with sing-song, rapid delivery. “Everybody in the world now has Strontium-90 in his bones, radioactive material, AND NOBODY had it…15 years ago…10 years ago. Strontium-90 did not exist. This is a new hazard to the human race, a new hazard to the health of people, and scientists need to talk about it.”

Strontium-90 was a particularly insidious component of fallout particles because it behaved like calcium in the body, seeping into bones and teeth and emitting radiation for decades. Scientists knew that large doses of radiation damaged human DNA and caused cancer. However, little research had been done on the health impacts of long-term exposure to low levels of radiation released by fallout. That left scientists concerned about the potential for genetic mutations due to fallout radiation, but they were unable to make definitive statements about health effects should innocent people be exposed to the radioactive particles.

Pauling, however, was confident that there was enough information to support what his conscience already knew: nuclear weapons tests were not worth the risk to one person, let alone humanity.

The assembly greeted Pauling’s message with an uproarious standing ovation. Some people filed out of the chapel. Others lingered. “What can I do?” “What actions can we take?” asked several of the students and faculty members.

These questions got Pauling thinking about a conversation he’d had the day before with Barry Commoner, a fellow activist and professor of biology at the university. Like Pauling, Commoner was outspoken about the need to stop testing nuclear weapons. The men had discussed writing a petition and getting it signed by American scientists. They hoped a public pronouncement would bring attention to the issue by revealing that many scientists agreed about the dangers of fallout. If thought leaders were forced to discuss the matter, then action, preferably ending weapons tests, might be possible.

Sitting around the dinner table at Barry Commoner’s home on the evening after Pauling’s speech, the conversation again turned to what scientists could do. Pauling suggested writing an appeal, sending it to American scientists asking them to sign it.

After eating, some scribbled phrases and others wrote paragraphs for the petition. Pauling turned their ideas into a short statement of 248 words that called for an international agreement to stop the testing of nuclear bombs between the three main powers, the United States, Soviet Union, and Great Britain.

The message proved timely. The next day most major American newspapers announced on their front page: Britain Explodes Its First Hydrogen Bomb in Pacific. These “dirty” bombs were 1,000 times more powerful than the first atomic bombs. They also released a greater amount of radioactive fallout. As of that day—May 15, 1957—all three nations addressed in the petition had tested hydrogen bombs.

Back in St. Louis, the scientists agreed on the final text of their appeal. They mimeographed it, attached a cover letter, and mailed copies of the petition to colleagues with similar politics and passions. Within one week, Pauling received several signed petitions at his house in Pasadena, California.

He prepared more copies of the petition, this time including the names of the first 25 signers. With the help of his wife, students and others at Caltech, they mailed out many copies of the petition, each with the names of the first twenty-five signers.

Envelope after envelope arrived at the Paulings’ house. It’s possible the mailbox overflowed with them because within ten days Pauling and his wife, Ava Helen, had signatures from more than 2,000 American scientists. The response overwhelmed them (and likely the mailman too!). Each envelope contained a petition with one, five, ten, twenty, and sometimes thirty or more, signatures. Sheets of paper piled up on the Paulings’ desk.

In early June, Pauling sent a copy of the petition with a list of the 2,000 signatures to Chet Holifield, a California congressman and chairman of the subcommittee studying the hazards of fallout. The press picked up the story, reporting it widely.

The petition also found support overseas. European scientists crossed out “American” in the title and first sentence of the petition, signed the altered version, and returned it to Pauling. Forty Belgian scientists of the Free University of Brussels signed a proclamation declaring their support for the petition.

Pauling and his wife, Ava Helen, hired a secretary to expand the campaign sending about 500 more letters and petitions to scientists around the world. Their effort more than quadrupled the number of signees.

In mid-January 1958, just eight months after his speech in St. Louis, Pauling and Ava Helen traveled to New York City to present the petition to the head of the United Nations. The next day the front page of New York Times reported “9,000 Scientists of 43 Lands Ask Nuclear Bomb Tests Be Stopped.” Linus Pauling with lots of help from family and friends had converted the passion sparked by one speech into the largest organized political movement among scientists in a decade.