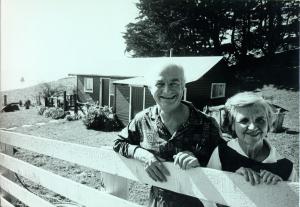

At Deer Flat Ranch, 1964. Arthur Herzog, photographer.

Creative Nonfiction by Melinda Gormley and Melissae Fellet

Big Sur and Pasadena, October 10, 1963

There was a knock at the door. Linus Pauling, the 1954 Nobel Prize winner in chemistry, got up from the breakfast table to greet a forest ranger from the nearby Salmon Creek station in Big Sur, California. The weather was pleasant, typical for fall on this Thursday morning of October 10, 1963.

“Good morning,” said the freshly shaven Pauling. White hair curled around his ears and at the nape of his neck. It had starting thinning at the temples years ago, and now at the age of 62, his receding hairline left the top of his head practically bald.

“Good morning Dr. Pauling,” the ranger said. “Your daughter called the station. She would like to speak with you.”

Pauling and his wife, Ava Helen, cherished the remoteness and wildness of their second home along the rugged coast of central California. Deer Flat Ranch was a 122-acre parcel of land overlooking the Pacific Ocean that they had purchased with the award money from Pauling’s Nobel Prize. With no electricity and no telephone, it was where they went to slow down from their usually hectic lecturing and travel schedules.

“Do you know what about?” Fear flickered in Pauling’s usually twinkling blue eyes.

The ranger tried to allay his concern. “It’s not serious.”

The ranger knew why Linda had called and he had promised not to ruin the surprise. Pauling likely relayed the news to Ava Helen when he returned to the table where she sat eating breakfast with their two guests.

A head taller than his petite wife, Pauling had found a match in determination and devotion when they’d met as undergraduate students in Corvallis, Oregon, in 1922. For the 40 years of their marriage, they’d lived in Pasadena. In his first 15 years there, Pauling had transitioned from Ph.D. student to chairman of the chemistry department at the California Institute of Technology. While he focused on his research and career, Ava Helen raised their four children. Now their children had families of their own.

The car jostled as they drove the mile of bumpy dirt road between their home and the ranger station. It was unusual for one of their children to try to contact them in Big Sur, and they likely tried to figure out why Linda had called.

“Daddy, have you heard the news?” Linda asked excitedly, when Pauling returned her call.

“No. What news?”

Ava Helen looked on through cat-rimmed glasses.

“You’ve been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize!” Pauling, stunned and unable to talk, passed the phone to his wife.

Pauling with Gunnar Jahn, ca. 1960s.

Linus Pauling, and his wife, Ava Helen, arrived at the Norwegian Nobel Institute for their 11:00 AM meeting with Gunnar Jahn. Pauling was likely dressed in a suit and tie. His hair curled around his ears and at the nape of his neck, and at 61 years of age, it had been thin on top for some time now. The petite Ava Helen stood a head shorter than him. Her spirit and conviction matched her husband’s and over thirty-nine and a half years of marriage they had come to see eye to eye on many civil rights and human rights issues.

A year and a half had passed since the 1954 Nobel Prize winning chemist had visited in spring of ’61 to deliver the opening address for the Conference against the Spread of Nuclear Weapons. Gunnar had become a good friend of the Paulings in recent years. The two men held similar views about nuclear disarmament and Linus appreciated his words of encouragement.

The couple was met by Gunnar’s secretary and taken to his office. As Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, he was one-fifth of the panel who determined the recipients for the Nobel Peace Prize each year.

Everyone exchanged greetings before sitting down. Gunnar seemed to speak and move a little more slowly with each passing year.

Eventually Gunnar explained why he had called them to his office. “Dr. Pauling, I tried to get the Committee to award the Nobel Peace Prize for 1962 to you.” Ava Helen and Linus were likely surprised to hear such confidential information.

Gunnar continued, his admiration evident. “I think that you are the most outstanding peace workers in the world. But only one of the four would agree with me. I told them, ‘If you won’t give it to Dr. Pauling, there won’t be any Peace Prize this year.'”

Perhaps Gunnar Jahn slowed down at two months shy of 79, but he still had moxie. During 1962 the Nobel Peace Prize was not awarded.

Celebrating in Pasadena, 1963.

Nearly a year had passed between the day that the Paulings sat in Gunnar Jahn’s office and Pauling received his daughter’s phone call and learning that in 1963 he was being awarded the 1962 Nobel Peace Prize.

Linus and Ava Helen Pauling were planning to celebrate that day, but for a different reason. More than 200 nuclear tests by the United States and Soviet Union during 1961 and 1962 had forced the countries’ leaders into diplomatic talks about prohibiting nuclear weapons testing, finally facing an issue that had been in the public debates for decades. The product of those talks, the Limited Test Ban Treaty, went in to effect that same October day in 1963. The treaty allowed underground testing of nuclear weapons, yet outlawed testing in the atmosphere, outer space, and underwater.

Pauling was one of many scientists who had been involved in the public debates around nuclear weapons testing, and he had worked for more than fifteen years to seek an international agreement of disarmament. Enacting the Limited Test Ban Treaty was a first step toward the peaceful world that Pauling envisioned, and the Norwegian awards committee recognized his ceaseless political efforts with the Nobel Peace Prize.

The phone at the ranger station in Big Sur rang with frequent calls, and Pauling responded to reporters’ questions about the prize for the next several hours.

“It is recognition of the work I and other scientists have been doing in educating people about the need for a treaty to end nuclear testing.”

“I have regretted the necessity of taking time from my scientific work for activities in the direction of world peace. But I have no doubt whatever about the correctness of my decisions. I’m glad I’ve done what I have done. I have no regrets.”

“I have no doubt that I shall continue to express my opinion publicly about any issue I feel is important and about which I feel I have something to say.”

He and Ava Helen drove back to their ranch to collect some of their things and then decided to drive the roughly 300 miles to their home in Pasadena. In their rush to get home, they forgot the bottle of champagne they had planned to drink that night to celebrate the Limited Test Ban Treaty.

Reporters went to the Pauling’s home in Pasadena. Not finding him there, many waited, ready to take pictures and ask questions.

Pauling arrived ready too. Hours of interviews at the Salmon Creek Ranger Station, along with the long drive home, had given him time to craft responses to the questions reporters asked most.

“Which of your two Nobel Prizes do you consider more significant?” asked a reporter from the Associated Press.

“Today’s, I think, perhaps because I feel so strongly about the need for peace and an end to human suffering from wars,” Pauling responded. “There may be another reason, too. Perhaps it’s because I view today’s prize as a reward for conscience and duty – the earlier prize came as a result of work that I enjoy so much. I have made many sacrifices over the years for the cause of peace. I would have been happier – except for the dictates of my conscience – to work solely in scientific fields.”

Following his curiosity and conscience Pauling achieved high public recognition as both a scientist and political activist. His two unshared Nobel Prizes – the 1954 prize in chemistry and 1962 peace prize – attest to this as do the many other accolades he received throughout his life.