Annotations by Linus Pauling, 1963.

[Part 5 of 5]

Once his televised debate with Edward Teller was concluded, Linus Pauling stated that the two would never meet again in a format of this type, as Pauling “considered [Telller’s] debating methods improper.” And though the two would indeed never again confront one another in public, tensions continued to build, if mostly on the side of Pauling.

In the lectures that he gave over the decades that followed, Pauling would regularly make a point of countering Teller’s arguments. Seeking to circulate his opposing viewpoint as widely as possible, Pauling likewise often wrote published responses to Teller’s articles and penned just as many (or more) unpublished letters to the editors of various journals that had printed Teller’s work.

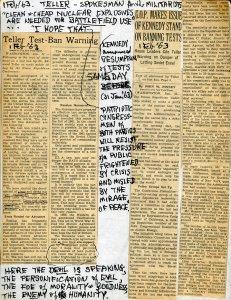

In marginalia notes written on a 1963 New York Times article titled “Teller Test-Ban Warning,” which Teller published nearly five years after the debate took place, Pauling’s animosity toward his opponent is perfectly clear. Reacting to Teller’s statement, “I hope that patriotic Congressmen of both parties will resist the pressure of a public frightened by crisis and misled by the mirage of peace,” Pauling expresses himself with an uncommon level of vitriol.

HERE THE DEVIL IS SPEAKING, THE PERSONIFICATION of EVIL, THE FOE of MORALITY & GOODNESS, THE ENEMY of HUMANITY.

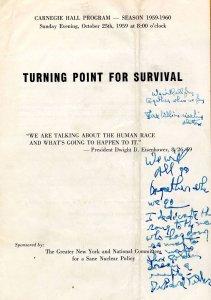

Program for an event sponsored by the New York chapter of SANE, 1959. Pauling has annotated: “We will all fry together when we fry/Three billion sizzling platters”; “We will all go together when we go/I dedicate this song to the man who has done so much to make the golden dream a reality – Dr. Edward Teller”

After the debate, Pauling pursued his activist platform in much the same vein as in his encounter with Teller, continuing to make the same points of contention and state the same facts. But in doing so, he not only countered points made by Teller, he also began to argue against essentially anyone who spoke out positively on issues of nuclear weapons development or a future nuclear war.

In one such instance, his article “The Dead Will Inherit the Earth,” published in Frontier in November 1961, Pauling attacked prevailing arguments made in favor of fallout shelters and their ability to save large percentages of American lives. Where Life magazine had suggested that fallout shelters might lead to survival rates as high as 95%, with Teller pegging the number closer to 90%, Pauling placed his own estimate at 0% within one year of hostilities. Such was Pauling’s estimation of the magnitude of any nuclear war that might be waged using the weapons that had been stockpiled and mobilized at that time.

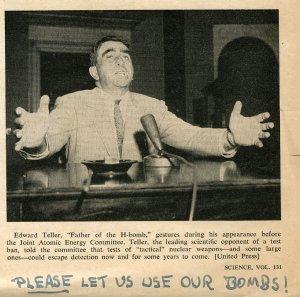

Detail from “Enforcing an Atom Test Ban: Scientists Testify Before Joint Atomic Energy Comittee,” Science, April 29, 1960. Annotation by Pauling.

Indeed, the late 1950s were a unique moment in world history, a time period during which the future was uncertain both in terms of geopolitics as well as the continued health and well-being of humanity. At the heart of these tensions resided, of course, the development of weapons far more powerful than anything ever seen before. While, during World War II, nuclear devices were initially viewed as symbols of strength and as a hope for peace, for many they quickly came to embody all that is negative in human society after they were used in Japan.

Though their viewpoints on nuclear weapons clearly resided on polar opposites of this dichotomy, a singular menace lay at heart of much of Teller and Pauling’s rhetoric: the threat of a third World War, one which would be far worse than any previous war, potentially resulting in the elimination of human life from the planet. This potential for crisis was a key factor in the escalation and continuation of the Cold War.

Both Pauling and Teller used these Cold War fears to bolster their arguments – clearly their positions would have carried far less weight without them. In doing so, both men attempted, in their own specific ways, to use data and statements of fact to alleviate public ignorance surrounding nuclear technologies. On the same token, both men also relied on a lack of conclusive data to make assumptions that would further support his point of view.

Summing Up

The 1958 debate, coupled with the books that both Pauling and Teller wrote later that year, demonstrate the broad diversity of ideas and tensions that surrounded the development and testing of nuclear weapons during the Cold War. Likewise, the story of the confrontation that emerged between these two men is central to understanding arguments over the continuation or cessation of weapons testing and development, and the emotional nature of the Cold War era.

Teller professed a desire to believe in Pauling’s position that the U.S. could maintain peace through international cooperation, but he was never able to arrive at this point. On the contrary, Teller, hardened by his own personal experiences as a Hungarian national, felt that the Communist bloc could not be trusted and that the U.S. ultimately had to keep the upper hand in nuclear technologies to keep its enemies in check. Teller viewed this tactic as the only route to avoiding a third World War. Deterrence, of course, required more weapons, and in order for new weapons to be developed, nuclear tests needed to continue.

As vehemently opposed as they were to one another’s perspectives, Pauling and Teller shared much in common. Their stances both emanated from their their views on the leading role that science should play in daily life, the need for scientists to be involved in the development of public policy, and the importance of developing policy through public dialog.

Both men were also essentially arguing for the same, or similar, outcomes: the education of the public on scientific matters and a quick end to tensions with the Soviet Union. Pauling and Teller likewise attempted to reach their rhetorical goals through a “translation” of science into language that laymen could understand. And although both hoped to change the minds of the public using reason and a better understanding of the facts at hand, each man ended up playing on fears in order to get their points across.

Though they went about it in very different ways, Linus Pauling and Edward Teller were both trying to prevent a third World War. Both agreed that war brings out the worst in humanity and that the next World War portended dire consequences. But as the debate unfolded, their vastly different perspectives brought emotions to the surface, at times revealing personal beliefs on nuclear weapons and on each other. For Pauling, the animosity that he felt remained consistent throughout his life, as he continued to be publicly critical of Teller’s work and role in the development of the hydrogen bomb.

About these ads