Interfaith families celebrating two or more religions are not actually “religious nones.” I sometimes describe my people as religious maximalists instead of religious minimalists. We may be atheists, or agnostics, or mystics, but we are determined to honor all of our religious heritages. Some of us spend double the time and effort on religious study and practice, rather than no time at all.

And yet, those of us with what theologian Duane Bidwell calls “multiple religious bonds” sometimes get swept into the catch-all category of “religious nones.” This happens because surveys do not let us check more than one box, and because researchers don’t really know how to deal with what they see as the theological dissonance of the way we practice and identify. So we get thrown into the “none” bin, with a tremendous variety of other fascinating, religiously complex, fluid and flexible people.

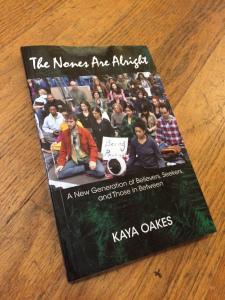

Writer Kaya Oakes paints detailed portraits of some of the people whirling about in this contemporary religious and spiritual kaleidoscope, in her slim yet revealing new book, The Nones Are Alright: A New Generation of Believers, Seekers, and Those in Between (Orbis Books, 2015). Oakes is the author of previous books including a spiritual memoir, and teaches writing at Berkeley: I have long admired her work in the literary online magazine Killing the Buddha. Rather than a dry academic study, she gives us clear and lively prose and even poetic phrases like this one: “…faith is a tidal motion, an ebb and a surge, a push and a pull.”

But the backbone of this book is journalism, which in this case means important qualitative research in an emerging field. Oakes interviews a series of (mainly) millennials who might find themselves in the “religious nones” category for a whole host of reasons. They grew up atheist, or grew disgusted with religious doctrine and became atheist. They continue to practice religion on their own terms while being agnostics, or go to divinity school while doubting the existence of God, or adopt Buddhist meditation alongside other traditions as part of “liminal” religious practice, or remain “believers” but disaffiliate from religious institutions because they cannot live under the doctrines oppressing women and queer people. Oakes describes how many of her subjects are involved in community service and social justice work despite their disaffiliations, and writes, “Lost in the hand-wringing over the rise of nonbelievers are these kind of stories.”

The book is clearly rooted in the author’s own complex, nuanced Catholic perspective–Orbis is the Maryknoll press. For those from other religions, the American Christian orientation is evident in the emphasis on “faith” or “belief.” (For Jews and Buddhists and Hindus and many indigenous peoples, practice and culture often have more weight than litmus tests of belief). And the second half of The Nones Are Alright focuses specifically on interviews with people who have left the Catholic Church, have perhaps rejoined it (“boomerangs”), and then sometimes left again.

But this is also one of the first books to emphasize the important contribution of interfaith families to the complexity of religion in America right now. Oakes cites Being Both: Embracing Two Religions in One Interfaith Family, and writes that future children are “increasingly likely to grow up ‘both/and’.” For instance, her portrait of “Carolyn” reveals how the daughter of a Lutheran mother and Jewish father worked for a mainline Protestant organization, studied in Israel but was alienated by the anti-intermarriage rhetoric there, briefly considered conversion to Judaism, and continues to seek out both Christian and Jewish experiences. She tells Oakes, “This whole idea about you don’t have to fit into a box has been useful and a relief.”

In all, the author gives us a tremendously useful disambiguation of the rich diversity of people caught up in the broad sweep of the nones. Millennials and those who come up behind them are in the midst of organizing their own religious structures and spiritual lives, and designing the new academic field of interfaith studies. In this context, the depth of each new portrait in this book will help to further our understanding of who is disaffiliating from religious institutions, why they are doing so, what the role of interfaith families will be, and how many of us are finding and creating meaning, support, and community outside the boxes in the 21st century.

Susan Katz Miller’s book, Being Both: Embracing Two Religions in One Interfaith Family is available now in hardcover, paperback and eBook from Beacon Press.