In our earlier article, The History of Absinthe, we touched briefly on the long-held belief that absinthe – and specifically the wormwood in it – taken in significant quantity will cause a drinker to go insane. This belief was one of the major motivating factors that led to a nearly century-long ban on absinthe in the US and much of Europe. In fact, the notion that absinthe causes hallucinations persists in pop culture and the public consciousness to this day, and is often played for humor in film and television.

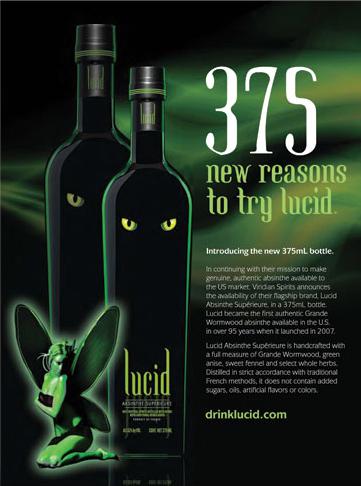

Absinthe has long been the victim of rampant misinformation, and the myth of hallucination and madness is one of the most persistent. Certainly, the notion of a liquor with drug-like qualities is compelling fuel for the rumor mill, but since the bans have lifted across Europe and the US, many absinthe distillers have done little to dispel the myth. What better way to market a product that was illegal for almost a hundred years than to capitalize on the appeal of its taboo reputation? Of course, this is not always the case. Newer distilleries like Vieux Carré and Leopold Bros are often more concerned with the craft and flavor of their spirit than its mystique. And yet it’s hard to deny that this ad from Lucid Absinthe, produced in France and one of the top brands internationally, is directly reinforcing the allure of the forbidden and the myth of hallucination.

Advertisement for Lucid Absinthe

But where does the myth come from? It seems unlikely that a simple rumor would gain so much traction as to inspire a ban across most of the western world. This question goes back over 150 years to the mid 1800s, when the Great French Wine Blight all but wiped out the wine industry across Europe, which made absinthe the de facto drink of choice for nearly every French citizen, rich or poor. Now, it’s important to note here that absinthe’s alcohol content is generally around 70-75% or 140-150 proof, which is about twice that of brandy and over seven times the alcohol content of most wines. For those drinkers who were already clinical alcoholics before the blight, taking up absinthe was perhaps the worst choice possible. It wasn’t long before European sanitariums saw a dramatic increase in patients who had a history of absinthe consumption. Once admitted, patients were denied alcohol and forced to dry out very suddenly. A set of consistent symptoms arose such as tremors, hallucination, agitation, nightmares, and in severe cases, seizures. These are, in fact, the symptoms of severe acute alcohol withdrawal, but 19th century medicine lumped all them together simply as “madness.” And with that, the misconception that absinthe leads directly to insanity was regarded as scientific fact.

Not helping the matter was the work of Dr. Valentin Magnan. Throughout the mid-19th century, Magnan conducted experiments in which he injected pure wormwood oil (wormwood being a key ingredient in absinthe) into lab animals. The result was severe seizures followed by death. It is from the work of Dr. Magnan that the chemical compound thujone was singled out as the supposed active ingredient, which caused absinthe drinkers to go mad.

Thujone is a chemical compound found in wormwood (along with many other herbs such as juniper, sage, and oregano) which acts neurologically as a GABA receptor antagonist. Essentially, thujone causes neurons to fire more rapidly than they otherwise would, which in sufficient quantities can cause muscle spasms.

But watch out, here comes the math. (Full disclosure: I am not a scientist. I didn’t even do that well in high school chemistry. If anyone who actually knows what they’re talking about finds fault with these conclusions, I would be grateful for additional insight.) Thujone triggers muscle spasms at a dosage of around 30 mg/kg. The average American male weighs around 86 kg. Therefore, in order to induce spasms, you would need a dosage of around 2580 mg. Pre-ban absinthe contains, on average, 25.4 mg/L of thujone. (Pre-ban absinthe is generally considered to contain more thujone than modern absinthe.) Therefore, in order to ingest enough thujone to induce spasms, an adult male would have to drink an estimated 101 liters (over 26 gallons) of pre-ban absinthe. And seeing as pre-ban absinthe is by definition over 100 years old, I’d bet dimes to dollars that there isn’t 26 gallons left in existence. But what’s the kicker here? Turns out ethanol (alcohol) has the opposite effect on GABA receptors than thujone. Essentially, the alcohol in absinthe is an antidote to the thujone.

In the 1970s the idea of absinthe as a drug got a boost when an article in the British scientific journal Nature noted that the structure of thujone is similar to that of THC, the active ingredient in marijuana. The author went on to theorize that thujone may have a similar effect on the brain as THC. However, when tested in 1999, this theory was conclusively proven false.

And yet, despite all evidence to the contrary, people continue to report having experienced psychotropic effects of absinthe. Even if individual accounts are not terribly compelling, the sheer volume of them over the course of the drink’s history deserves attention. Now myself, I am inclined to believe the science. But there are many other people who will continue to insist that absinthe induces hallucinations. And not surprisingly, these are the same people who are most likely to claim that they have experienced these hallucinations.

The persistence of individuals who report absinthe-induced hallucinations is, in my opinion, the triumph of a mid-19th century coalition of religious activists, prohibitionists, and wine industry lobbyists. Together with some shoddy science, these activists created a steady, consistent stream of misinformation that over time gained an air of truth.

For a hundred years those who made enough effort to actually acquire the illicit spirit were almost unanimously looking to experience some sort of hallucination or high. Expectation and conviction are powerful forces, and those expecting an altered state are much more likely to believe they’ve achieved one whether or not it has any neuro-chemical basis.

It seems that 150 years ago a group of fools and naysayers created a fiction so compelling that it verges on reality by sheer conviction. Yet for me, I prefer absinthe as it truly is, a nuanced and unique spirit. And perhaps I’m just a nerd, but I find the history of the drink and the history of its reputation far more interesting than any hallucination.