Harvest Mitchell Gymnasium

How do you develop a legal practice that has lasted roughly half a century and produced court rulings that have achieved justice and transformed American society. Alabama's Donald Watkins has learned you don't do it on your own. It takes inspiration and determination of courageous people from various walks of life. In Watkins' case, he has been driven by a high school coach, a janitor, the family members of an unarmed man gunned down by police. Inspiration also has come from individuals whose names come straight from history books and are know by virtually all Americans.

What has the journey been like? Watkins describes it, in a post today at donaldwatkins.com, under the headline "A Tribute to Coach Harvest Mitchell, a Man of Class, Character, Honor, and Greatness." While many people, some of them famous, have played roles in Watkins' push for justice, one particular person is on his mind today.Writes Watkins:

I have been privileged to meet many great Americans on my journey through life. Coach Harvest Mitchell is one of them.

This article constitutes my personal tribute to Coach Mitchell, one of the bravest and greatest men I have known during my 46-year legal career.

I was born into the family of Levi and Lillian Watkins. They were my parents and first set of heroes.

As a young child growing up in Montgomery, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was my pastor, Sunday School teacher, and Baptist Training Union instructor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Rosa Parks was my mom’s close friend and a frequent visitor to our home.

The NAACP, America’s oldest civil rights organization, awarded me a scholarship to desegregate The University of Alabama’s law school. It was there that I met Mr. Ramus Rhodes, the remarkable “janitor” who would mold me into a prolific and effective litigator.

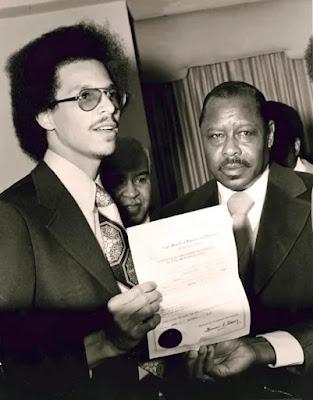

Donald Watkins and Scottsboro Boy Clarence Norris.

After law school, I met and represented Clarence Norris, the last known surviving “Scottsboro Boy.” We fought for two years to secure a full and unconditional pardon from the State of Alabama for Mr. Norris. The pardon, which was awarded in 1976, ended a 45-year legal fight to clear the nine innocent Scottsboro Boys of trumped-up rape charges involving two white women

In 1975, Ida Mae Whitehurst and her daughter-in-law, Florence Whitehurst, gave me an opportunity to reform the Montgomery Police Department. Their case involved a police execution of an unarmed and innocent Bernard Whitehurst on December 2, 1975. After officers realized they had killed the wrong man, they engaged in a massive cover-up of the shooting. They also planted a “throw-down” pistol by Whitehurst’s dead body and falsified witness statements.

The Whitehurst case evolved into a nationally recognized scandal that resulted in the resignations of Montgomery’s mayor and police commissioner, the indictment of three police officers, and the firing or resignation of eight others. On April 3, 1977, the Washington Post called Whitehurst's case, “Alabama's Watergate."

That leads us to a man who was known as a highly successful high-school coach in football, basketball, and track and field. Ironically, in a state that reveres its White coaches -- Nick Saban, Paul "Bear Bryant, Ralph "Shug Jordan -- this Black coach was forced to operate mostly in the shadows, receiving little credit for his achievements until after his death. Writes Watkins:

In 1976, I met and had the privilege of representing Coach Harvest Mitchell in his career-long fight to implement fair employment and promotional practices within the Florence City School System.

Coach Mitchell was employed for 35 years by the Florence City Board of Education, where he coached different sports and taught physical education and health. Mitchell made his mark as a head athletics coach, spending ten seasons at Burrell-Slater High School and seven at Coffee High School.

Mitchell was head football, basketball, and track coach at all-black Burrell-Slater from 1959 through 1969. Mitchell built Burrell-Slater into a North Alabama sports powerhouse.

During his 10 years at Burrell-Slater, Mitchell’s record in basketball was 209 victories and 46 loses; in football, it was 55 victories and 19 loses. Mitchell was nominated for basketball coach of the year eight of those 10 years and won five times. Mitchell also was chosen coach of the year in football once. These impressive achievements were complemented by the successful tournament participation of teams under his direction. Mitchell had no assistant coaches.

In 1968, Mitchell was inducted into the Sports Hall of Fame in Madison County, Alabama.

Yet, the Florence Board of Education refused to award Mitchell a head coaching job at the predominantly White Coffee High School after Burrell-Slater was closed in 1969 (due to a court desegregation order). Mitchell applied for a vacant head coaching position in football after the 1969-70 season ended and a head basketball coaching job during the 1970-71 school year. Both applications were rejected in favor of lesser qualified white applicants.

On March 6, 1972, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ordered U.S. District Judge Frank H. McFadden to award the head basketball coaching job at Coffee High School to Harvest Mitchell. Judge McFadden, who was affectionately known in the state’s white community as “Big Red,” was notorious for denying judicial relief for deserving Black plaintiffs in school desegregation lawsuits.

Frank McFadden, an “old school” Mississippi native, regularly used the N-word in his private conversations about Black litigants.

Harvest Mitchell coached basketball at Coffee High School for four seasons, while also serving as an assistant football coach. The school, fan, and booster support Mitchell enjoyed at Burrell-Slater was replaced by tidal waves of racial hatred and resentment from the administration, fans, and boosters of Coffee High School.

I represented Harvest Mitchell when the School Board tried to replace him with a white basketball coach whose objective qualifications for the job were inferior to Mitchell’s. We returned to Judge Frank McFadden’s courtroom to fight for Mitchell’s job. After a lengthy trial, McFadden, once again, refused to enforce Mitchell’s constitutional right to fair employment practices.

Coach Mitchell withstood unbearable racial prejudice at Coffee High School without flinching or allowing it to bother him or impair his coaching abilities. To this day, Coach Mitchell is one of the greatest personal heroes in my life.

On November 10, 2023, the honor and respect from the Florence City Board of Education that eluded Coach Harvest Mitchell in his life was conferred upon him in death. On that day, the Board of Education renamed the Burrell Slater Gymnasium in honor of Coach Mitchell. This board action was a fitting tribute to a man who loved everybody in the Florence City School System, even when they did not have it in their hearts to love him back.

In the end, Harvest Mitchell was more than a coach, more than a man who racked up dazzling won-lost records in the world of sports, more than a teacher. He left a big mark by making the workplace more fair and just for everyone. And he did it in a time and place where prejudice was woven into the fabric of employment -- and that had to be gut-wrenchingly difficult. Donald Watkins puts Harvest Mitchell's life in perspective:

May Coach Harvest Mitchell’s unconquerable spirit, unconditional love for humanity, and quest for excellence in the classroom and sports arena live on in our hearts forever!

I am so blessed to have represented Harvest Mitchell and write this beautiful ending to his story. In the end, Harvest Mitchell's unconditional love for humanity conquered every roadblock that kept the Florence City School System from formally recognizing his greatness as a man and a coach.

Never, ever underestimate the power of God and the fighting spirit of men who will not allow the indignities of other men to rob them of their manhood.

Martin Luther King (left) and Rosa Parks