On August 30, 1983, almost exactly 250 years after the birth of famous chemist Joseph Priestley, Linus Pauling was offered the most prestigious award granted by the American Chemical Society: the Priestley Gold Medal.

The medal, granted to an individual who has made tremendous and innovative contributions to chemistry, was established in 1922. Initially awarded every three years, the ACS decided in 1944 to make it an annual prize. The Society elected to name the prestigious award after Priestley as his work with gases influenced the field of chemistry as well as general science, and his interests in a whole host of other areas made a significant impact on a number of additional disciplines, including political theory and religious practice.

By the time that Pauling received the Priestley Medal he had been affiliated with the American Chemical Society for over fifty years, and many were shocked to discover he hadn’t already received the award. As an ACS past president as well as the recipient of the Irving Langmuir Award in Chemical Physics, the ACS Award in Pure Chemistry, and the Willard Gibbs Award, he was certainly a lauded and highly decorated member of the society. For many, the explanation for his omission could be sourced to the generally conservative political viewpoint espoused by of the ACS Board of Directors.

For many years prior to his receipt of the award, Pauling had played an active role in the Priestley Medal selection process. Notably, in 1949 he nominated the eventual recipient, Arthur B. Lamb, as an acknowledgement of Lamb’s work as editor of the Journal of the American Chemical Society as well as his contributions to inorganic chemistry and the structure of complex ions. By then, Lamb and Pauling had enjoyed a lengthy correspondence as the former would often send manuscripts to Pauling to edit and evaluate for inclusion in JACS.

The following year Pauling nominated W.F. Giauque, a Canadian chemist who focused on chemical thermodynamics. While Giauque was of four finalists, the 1950 Priestley Medal instead went to Charles A. Kraus. Pauling was among the pool of thirty-three individuals nominated for that year, but did not make the cut to the final four.

“The Dickinson College Award, In Memory of Joseph Priestley,” presented to Pauling in 1969

“The Dickinson College Award, In Memory of Joseph Priestley,” presented to Pauling in 1969In 1969, Pauling won a different award named after Joseph Priestley: the Priestley Memorial Award from Dickinson College, home to the largest Priestley collection in the world. Pauling was selected for this honor because of his “significant contributions to the welfare of mankind through his research in physical chemistry.”

As a component of his trip to accept the award, Pauling spent two days on campus interacting with students and faculty, and discussing what was then his primary concern: the deployment of anti-ballistic missiles, or ABMs. Pauling considered the mere idea of ABMs to be “silly” and more of a threat to the nation than a tool to provide security. Pauling further believed that governments, especially the U.S. government, should instead be focusing on the “lopsided distribution of the world’s wealth,” which he regarded to be “a chief problem.”

Pauling receiving the Priestley Medal from an unidentified ACS representative.

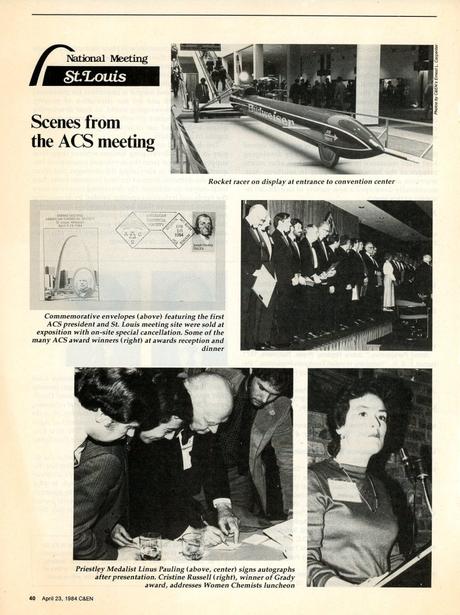

Pauling receiving the Priestley Medal from an unidentified ACS representative.The symposium to recognize the awardee, titled “The Legacy of Joseph Priestley,” was held in Washington D.C. on April 9, 1984, and honored not only Pauling but also another thirty additional recipients of ACS awards. Derek Davenport, a chemist and historian then serving as chair for the ACS Division of Chemical Education, proposed and helped organize the symposium, advocating for Pauling as the awardee from the very beginning. Since Ava Helen Pauling’s death in 1981, Linus Pauling had drastically scaled back his travel schedule, but he was glad to make a trip to receive this special award, named for a historical figure whom he greatly admired.

At the symposium, Pauling received a gold medal bearing the likeness of Joseph Priestley, as well as a bronze replica. In addition to his acceptance address, to be delivered during the symposium’s opening ceremony, Pauling was obliged to participate in several interviews with the Society’s radio program, “Dimensions in Science,” as well as a meeting with local school teachers, another radio program called “At Your Service,” and an appearance on a local television program called “Newsmakers.”

Pauling’s acceptance address proved controversial. Titled “Chemistry and the World of Tomorrow,” the lecture was penned as a sequel of sorts to “Chemistry and the World of Today,” Pauling’s ACS presidential address from 1949.

Thirty-five years before, Pauling had discussed how the entire world was affected by chemistry, stressing the imperative that the ACS take a political turn to address society’s needs in the wake of World War II. Pauling’s 1984 talk was much more in line with his recent anti-war rhetoric and included criticisms of industrial chemists who had contributed to the advancement of the nuclear arms race. In particular, Pauling felt that chemists had been ignoring their obligations as global citizens for far too long while they focused on the science of war, and he made it known that this shirking of responsibility had angered him to no end. Suffice it to say, this component of the address was not received warmly by many of the chemists in the audience.

Pauling also made a point to refer to George Kistiakowsky, who had passed away less than a year earlier. Kistiakowsky was a physical chemist who had advised President Eisenhower from 1959 through 1961, and who had warned about the effects of nuclear proliferation. Pauling embraced his words and carried their sentiment throughout his speech, quoting Kistiakowsky as follows:

…and so here we are, possessors of some 50,000 nuclear warheads, more than enough to produce a holocaust that will not only destroy industrial civilization but is likely to spread over the earth environmental effects from which recovery is by no means certain…there is simply not enough time before the world explodes…the threat of annihilation is unprecedented.

For many, Pauling’s rhetoric sent a chill through the room. Once he had completed his remarks, all of the other award recipients being honored were presented, and one-by-one Pauling sought to shake their hands in congratulation. One man refused to engage in this way, leaving Pauling shocked and upset. Derek Davenport, the event organizer, later reflected that

We were treated to an uncharacteristically graceless litany of evils of the military industrial complex and the necessity for eternal vigilance on the part of the concerned scientist. Not surprisingly, the enthusiasm of the industrial chemists was distinctly muted and it was a rather glum Linus Pauling who assumed his seat in the center of the platform.

In the days following Pauling’s poorly received address, the ACS Board of Directors contacted previous recipients of the Priestley Medal to solicit their opinion on changing the address format during the opening ceremony. In this solicitation, the head of the Board Committee on Grants and Awards, Joseph Rogers, recommended shifting the acceptance address to a later date in the symposium and devoting only 10-15 minutes to an introduction of the awardee on the first day. In support of this change, Rogers cited the growing length of the opening ceremony as well as the presence of an audience that was mostly not of a scientific background.

Pauling responded to this proposal with disapproval, noting that the medal is “described as the greatest honor that the American Chemical Society can bestow.” Recipients then should logically have the opportunity to address the public at the initial gathering and to share their point of view in the spirit of the medal’s namesake.