I lived in Russia for most of my early twenties. I studied at Leningrad State University, worked in St. Petersburg and Moscow and, visited countless other cities and towns as well. I have never stopped being completely enchanted by White Nights in St. Petersburg and never tired of exploring Moscow’s hidden treasures. The cupolas of the Assumption Cathedral in Sergiev Possad, painted a deep cobalt blue with a scattering of golden stars, always leave me deeply awed.

White Nights in St. Petersburg,

one of the sights I would like to

show my husband, but can't.

Photo by Victor Griagas

I would love to show my son and husband the places that I lived in, places that I grew to love so deeply when I lived there. But, I can’t, I won’t. You see, my husband is not Russian, he is Kyrgyz. To most readers, this means precisely nothing. To people from this area of the world, no further explanations are needed.

Russia is and always has been a multi-ethnic nation. Today, there are almost 200 different ethnic groups living in Russia from Abkhazians to Yakuts. Some people in Russia are white skinned and European looking, including Russians, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians. Others such as Armenians, Azeris, Georgians, and Chechens more closely resemble Mediterranean peoples like Italians or Greeks. Still further east are the peoples of Central Asia and the tribes of Siberia, who are Asian looking, more resembling Mongolians. The tribes of Russia’s Far North are most similar to their cousins across the Bering Strait, Alaskan Eskimos. You can read more about Russia’s ethnic mix in two earlier posts that I wrote here and here.

Jewish victims of Russian Pogroms.

It was not until I lived in Russia full time that I began to understand and grasp the full range of ethnic stereotypes and how these ideas impact on Russian and post-Soviet society. This complex interplay between nationalities and nations is a constant undercurrent that is ignored at one’s own peril. Ethnic hatred and directed violence are certainly nothing new to Russia. My mother’s grandparents fled Tsarist Russia during anti-Semitic pogroms over a hundred years ago. I was always cautious when I lived there, not telling anyone that I was Jewish by heritage. But I had the freedom to cloak my background and if anyone probed beyond “American,” I could always hide behind my very Irish name.

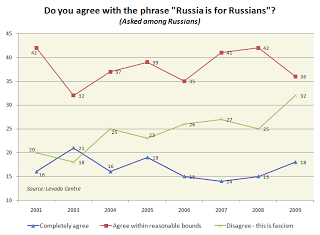

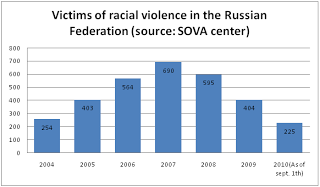

My husband (and millions of others like him) is not as fortunate, as his ethnicity is written in the color of his hair, the shape of his eyes, and the hue of his skin. Soccer fans in St. Petersburg have taunted minority players with bananas and last year demanded that Russian National Champion team, Zenit, “preserve the traditional identity” of the team by not signing dark-skinned or gay athletes. In polling citied by an extensive article on Russian xenophobia, “One in five Russians strongly agrees with the slogan ‘Russia for Russians,’ while 43 percent believe that any measure taken to protect “my people” is good, according to research by Higher School of Economy professor Mark Ustinov. Nearly 70 percent of Russians have negative feelings toward people of another ethnicity, Ustinov’s research found.”

When I talk about my concerns about traveling with my husband to Russian friends, they look at me in surprise and protest, “But, your husband is not like those people! He is a professional!” In my mind I often respond that I don't think a racial attack starts with a resume review.

and in all honesty made no connection between my Central Asian husband and the Central Asian migrant workers he despised for ruining Russia.

Imagine my surprise when we were at a company picnic in Las Vegas a few years ago and one of my husband’s co-workers blithely informed me that he was “not a real Asian.” My husband’s office was made up primarily of Chinese and Chinese-American technology workers and I was shocked to realize that none of them considered him Asian. In fact, they considered him Caucasian. Recently, I was discussing mixed race (Asian/Caucasian) marriages and specifically the phenomenon of white men actively seeking out Asian women to marry, or what my friend called “Yellow Fever.” My friend is American, of Chinese heritage, and when I asked her if she considered my dark skinned, dark haired husband Asian, she promptly answered, “no.” When I probed a bit deeper, she told me that maybe it was because he speaks Russian that she doesn’t consider him Asian, but she really wasn’t sure. Another friend of Japanese and African-American heritage, who proudly considers herself a “person of color” told me that she doesn’t consider my husband Asian because he is light-skinned.

Imagine the irony – in Russia, my husband could be the target of vicious taunts and possible violence by merit of the color of his skin, the shape of his eyes. Many Russians would not hesitate to point out that my husband’s “kind” was not wanted in Russia. Yet, here in America, he is not even considered a “real Asian” by a considerable swath of the Asian community. Even white friends don’t necessarily consider my husband Asian, which I also find fascinating. Each person’s perception of my husband seemingly throws up a reflected image of the world in which that person lives.

By Kelly Raftery