Red carnations left anonymously in the Valley Library Special Collections and Archives Research Center foyer on February 28, 2018 — Pauling’s 117th birthday.

[Extracts from an interview by Tiah Edmunson-Morton with Chris Petersen, conducted on the occasion of the Pauling Blog’s tenth anniversary. This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity. Part 4 of 4.]

Tiah Edmunson-Morton: Do you see yourself as his biographer?

Chris Petersen: Oh no, definitely not. But here is what I do see myself as. I see myself as a person who, through pure accident, wound up in a very unique position. I was hired as a student assistant in 1996, I was hired as a full-time [faculty member] in 1999, and that was the period of time during which the collection was being processed. And somehow I took charge of that when I was a student. The person who had my job before me left in the spring of my senior year of college, and at that point I began to lead the processing effort of this enormous collection. And that continued.

We published the catalog in 2006, so that’s ten years of work based on my start date as a student. And that’s never going to happen again. Nobody’s ever going to re-process the Pauling Papers. I hope not, at least. [laughs] So I had this opportunity that nobody else will ever have. And when you work with a collection, you don’t necessarily become their biographer, but you do have a level of intimacy with the material that nobody else will ever have, because nobody else is going to process that collection.

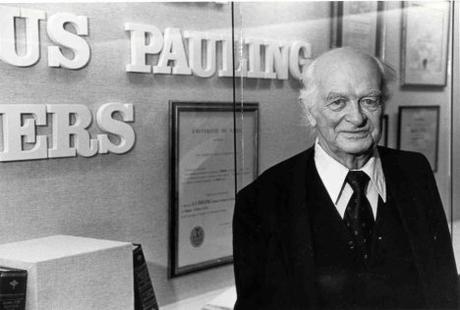

Linus Pauling in the original Special Collections reading room, 1988.

And now when I think about the blog I think about it in multiple ways, but one of the ways that I think about it is it being a resource for future archivists who work at OSU to be able to work with this collection in a more effective way, just because they’re not going to have that same experience of working with it that I had. And part of what continues to motivate me to publish the [Pauling Blog] is that — to leave a little bit of my experience behind after I’m gone. Because the blog will hopefully continue to exist. I doubt it will continue to be published after I stop doing it, whenever that is, but what we’ve done will continue to exist. We’re archiving it with our Archive-It instance, so it’s in the Internet Archive. It gets archived once a quarter.

And I’m happy about that. It’s a very big collection, it’s difficult to provide reference for it because of its size, and it’s unfair for all of the people who work here to be expected to know it on anything more than a surface level. So this is a tool for them to have in the future.

TEM: Is there a post that you thought about writing, because of the depth of knowledge that you have about the collection, that you decided not to write?

CP: Yeah, I thought about writing something [for the tenth anniversary of the Pauling Blog] but we’re doing this instead. [laughs]

There’s a part of me that wants to write a reflection about my engagement with Pauling, a person I never met. He died when I was a senior in high school; actually the summer after my senior year of high school. I was working for the Department of Transportation picking up garbage by the side of the road in Eastern Oregon on the day that he died. So that was my status at the end of his life. But I have come to know him well through strange ways, and I have come to know his oldest son quite well – Linus Jr. – through oral history. And I was in the middle of this department [Special Collections] that doesn’t exist anymore, that was devoted to him. And that’s, again, a unique experience.

Part of my oral history work, in addition to Linus Jr., was to interview Cliff Mead – basically the only head of Special Collections that ever existed – to try to get some of his memories from the chapter before I came along in ’96, because there were nine years of time that elapsed. So I could have a history of Special Collections recorded somewhere.

And anyway, part of me has thought about writing these recollections down, but it seems like a lot of work [laughs] and I have other things to do right now. But maybe someday.

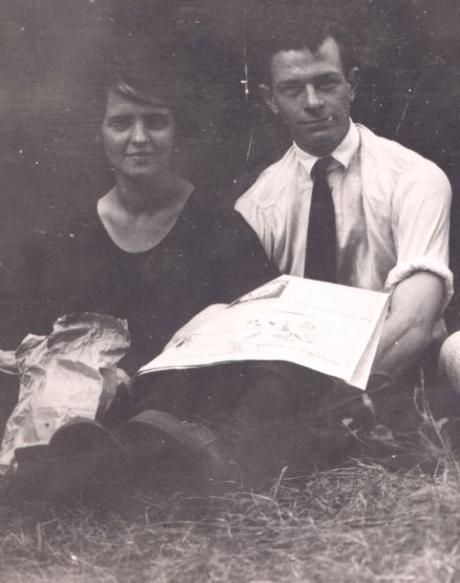

Ava Helen Miller with Linus Pauling, 1922.

TEM: What about topics that you’ve thought about writing about? I mean, there’s some really personal relationship stuff between he and Ava Helen.

CP: Yep. That’s actually a good example of something that I’ve thought about and haven’t done. So they were separated for a year when he went to Caltech and she was here [at Oregon Agricultural College]. They wanted to get married and their parents wouldn’t let them, so she stayed here in Corvallis for a year and he went for his first year of grad school. And then he came back that next summer, they got married, and they went off together. But they were apart for one year and they wrote to each other basically every single day, and we have all of his letters but none of hers, because he burned them. And I think that there’s probably good stuff in those letters but I just can’t deal with it because there’s also a lot of lovey-dovey stuff, and there’s just a lot of stuff period.

But I think that the correspondence between he and Ava Helen is ripe for mining, and Mina Carson did some of that for her Ava Helen biography. Pauling was super formal in his correspondence and pretty much to the point, because he was doing a lot of corresponding and just was a very busy person. The one time where he reveals himself on any deeper level, or reveals any kind of vulnerability, is in his correspondence with his wife. So I think that there’s probably a lot there that could be thought about and teased out, but it would take a lot of time and thinking to try and figure out what exactly is going on here with some of that stuff. But that’s something that I would like somebody to do some day; that’s definitely at least a paper, if not a book.

Something that I would like somebody else to do that definitely is a book is to talk about his relationship with Caltech. He was there for a long time and it would be really interesting to trace his evolution while there and also to trace the Institute’s evolution while he was there, and think about how the two of them were symbiotic on some level. I mean, Caltech was not Caltech when he joined, and it is Caltech today in part because he was there. He helped to build that place. He certainly wasn’t the only person, but he was a significant piece of it.

And on the same token, when he went to Caltech — he came from an extremely humble background and he’s lucky to have made it out of that background. When he went to Caltech he was very smart and ambitious but super green. I mean, his education that he got here was, I think, pretty modest. OAC was a land grand institution, it was focused on practical stuff, and he had far greater aspirations than that.

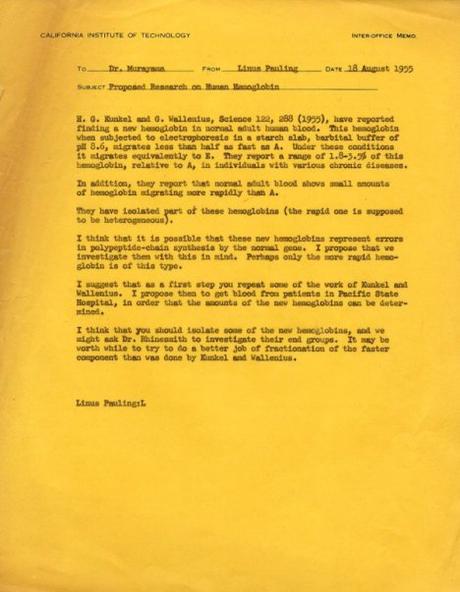

Hand-tinted photo of Pauling at the Sutherlin work site, 1922.

And he got into Caltech — one of my favorite stories about Pauling is that, so he’s been accepted to Caltech and the summer before he goes down there he’s working for the Department of Transportation and he’s a pavement inspector. And so he’s out in the middle of nowhere in Oregon, inspecting pavement and living in a tent. But before he embarked upon this job he wrote to A.A. Noyes, who is the head of the Chemistry section of Caltech — there are basically three people who started Caltech and Noyes was one of them — and Pauling says, “I’m coming to grad school, how do I become a grad student?” And Noyes is writing a textbook and he sends him a manuscript version of the textbook and tells him, “Do all the problems in this book.” And so that summer in his tent, with a lantern, Pauling is doing this work and learning how to become a grad student and how to become a scientist.

And so he goes to Caltech and he’s there for a few years and at the end of that he gets this Guggenheim fellowship to go to Europe to learn quantum mechanics as it’s basically being invented. And then he comes back to the United States, applies quantum mechanics to structural chemistry, publishes a series of papers that become The Nature of the Chemical Bond in 1939, and that’s Nobel-quality work at that point. And it’s a very short period of time during which this process is moving forward, but for me it begins in that tent.

In any case, Caltech was hugely important for Pauling and vice-versa, and I think that would be a book that somebody should write; I’d love to see that. That’s not a series of blog posts.

One of the things that we’ve done a lot is to talk about his associations with places. We’ve done a series on his tenure at the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, which was rocky at best and short-lived. Same thing with UCSD. We’ve got a series coming out soon about his time at Stanford. We’ve done a lot on his relationship with Oregon Agricultural College too. But it’s harder to wrap yourself around the relationship with Caltech because he was there for so long and so much happened.

But I think I figured out a way that we can start to engage with that a little bit, and that’s something that’s being worked on right now, and that’s to talk about his work as an administrator. So he was the head of the Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering for a long time and he was in charge of a lot of grant money and he had an army of grad students who worked for him. And part of his success story is that he was a very able administrator, and obviously a brilliant thinker.

So he’d come up with an idea and give it a grad student, and that might become that grad student’s entire career basically. They would pursue that as a grad student and continue to pursue it for the rest of their career. It was something that would emerge from this yellow piece of paper that he would give to people, saying “you can work on this if you want, you don’t have to.” It was implied that you should. [laughs]

But he published 1,100 papers and you don’t do that without help. And there are plenty of co-authors there and people who went on to win Nobel Prizes — the Pauling tree is vast and significant. So I’m interested in that; I’m interested in his ability to be a leader of men. And it was men, because Caltech didn’t allow women. But I’m interested in his ability to attract grant money and how this all flows into creating this career that is so remarkable. And a lot of it happened at Caltech; a lot of the best stuff happened at Caltech.