There are a lot of drinks in the world. From British best bitter to choujiu (Chinese rice wine), everywhere human beings have put down roots, you’ll find some sort of booze. And of all the beverages that have ever passed human lips, perhaps the most infamous is absinthe. This bright green spirit can boast the king of bad reputations, so much so that it was demonized and banned in several western countries for nearly a century. But what led to such drastic actions? What had influenced public opinion so dramatically against absinthe? This is a question that has been neglected, perhaps intentionally, for quite a long time; and to do it justice – unfortunately – requires quite a long answer.

An amateur preparing a dram of absinthe.

By most accounts, absinthe was invented some time in the late 18th century. Wormwood, the infamous active ingredient, had been in use medically since ancient times; and like many other spirits, absinthe was almost certainly developed as a medicine. In addition to wormwood, fennel and anise also lend flavor to the spirit, which got its first boost of popularity thanks to the French military. Throughout the 1800s European imperialism was divvying up what it considered to be the “uncivilized world” which, more often than not, tended to include hot, damp, and bug-infested climates. In an attempt to ward off malaria, French troops were issued absinthe – a medicine they were none too reluctant to take. As the soldiers started coming home, they began ordering absinthe in cafes and serving it in their homes. Thus began the French’s notorious infatuation with absinthe, which would in turn inspire and plague them individually, socially, and internationally.

In the early years of absinthe’s popularity in the francophone world (through the early and mid 1800s), the spirit enjoyed a brief period of chic respectability. It was, after all, returning soldiers and war heroes – many of whom were officers and therefore upper-class – who advocated for the drink. In many of the best houses of Paris it was customary to serve absinthe as an aperitif (an appetite stimulator served just before supper), though considered bad form to enjoy more than one.

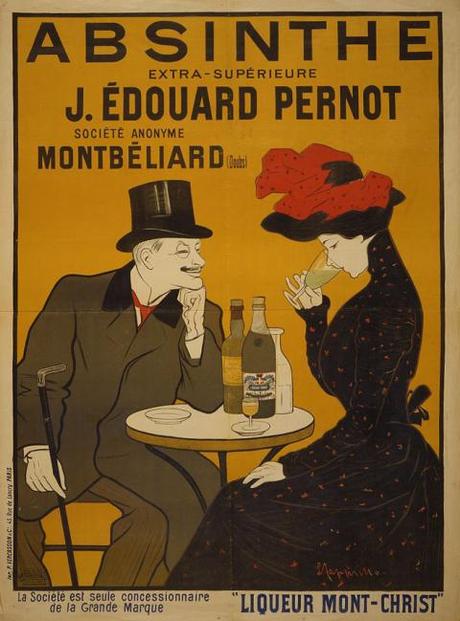

An early ad for Pernod. Though since the ban, Pernod hasn't produced a true absinthe.

Then everything changed. In the late 1850s, Europe saw one of the most profound shifts in alcohol history since the invention of distillation: the Great French Wine Blight. Over the course of almost 20 years an aphid native to the Americas all but destroyed the wine industry across Europe. France was hit especially hard. It wasn’t until the early 1870s that a method of grafting aphid-resistant American vine roots was conceived and adopted. In the intervening years, wine and brandy (including cognac and armagnac) became prohibitively expensive to all but the super rich, and even to them supply was unreliable.

This shortage created a major shift in the drinking habits of the entire western world. Among other things, it led to the legitimization of whiskey (especially Scotch whisky, thanks to Queen Victoria) among upper class British and Americans who could no longer find or afford cognac. In France it meant that for the first time, absinthe was cheaper by volume than wine, and far more potent. Not unexpectedly, absinthe’s new status as economy booze alienated the wealthy and made it the preferred drink of the poor, the working class, and (most abhorrently to the Paris elite) artists.

Writers, poets and painters took to absinthe with gusto. Preparing a glass of absinthe became a ritual, dripping ice water ever so slowly over a cube of sugar into the deep green spirit. And as the absinthe dilutes, drop by drop, the clear emerald hue turns cloudy in billowing waves called a “louche.” (More on this later in the week.) Such a display was bound to attract the aesthetically inclined, and scores of artists and writers claimed that absinthe granted them inspiration, somewhere around the third or fourth glass. According to many, the green fairy was also a muse.

This association with artists and bohemians continued into the early 20th century, La Belle Époque, and the reign of Toulouse-Lautrec. The legendary painter and his circle of bohemians that haunted the infamous Moulin Rouge are perhaps the most strongly associated with absinthe drinking even today. It was said that Lautrec’s cane doubled as a discreet absinthe flask.

Aside from fashion, art and issues of social acceptance, the rise of absinthe amongst the working class and bohemians brought up more practical concerns. Absinthe’s is, regardless of brand, an extraordinarily potent liquor with an ABV usually around 70-75% or 140-150 proof. That’s twice as strong as most whiskey, gin or vodkas. For those already inclined to overindulge, replacing their daily wine or brandy intake with absinthe posed a serious risk.

While the increased risk of alcoholism was (and remains) a legitimate concern; in the late 1800s, the upper class, the medical community, and religiously motivated prohibitionists took the issue to sometimes absurd extremes. During this time period Darwinism was still a new and poorly understood concept, though the idea of evolution had made its way into the public consciousness. This resulted in many individuals, with only a partial understanding of Darwin’s actual theory, to apply it far beyond the scope of biology.

Social Darwinism was a notion that justified the aristocratic view of the proletariat as less-evolved brutes, prone to vice, crime, and possessing little willpower. The introduction of absinthe to the teeming masses raised a fear among the elite that the working class, the solid foundation of society, would crumble into crippling alcoholism and lead to the collapse of French civilization.

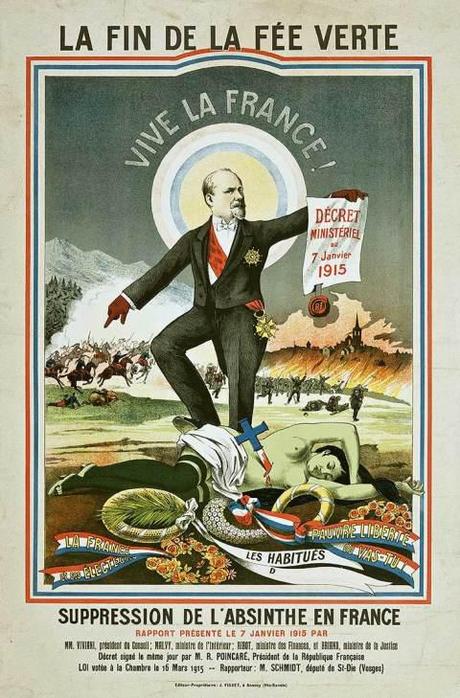

Anti-absinthe propaganda began popping up all around Europe

Amongst doctors, there was a concern that absinthe drinking amongst working class women would cause de-evolution. Though it seems silly now, many scientists of the day suspected that prolonged absinthe drinking would lead to the de-evolution of the lower classes, producing a separate inferior species of humanity.

Other medical concerns which have had more prolonged support, lasting well into the 20th century, include the threat of insanity. Hallucinations, hysteria, and other varieties of “madness” were reportedly linked to absinthe drinking. This, however, is a topic all its own, which we’ll explore later in the week.

The result of all this bad press was a coalition of prohibitionist groups, religious organizations, misguided medical professionals, and the socio-economic elite, all fueled by pressure from the slowly recovering wine industry pushing to defame and demonize absinthe. All this powder keg needed was a match, and his name was Jean Lanfray.

Lanfray was a French-born farmer living in Switzerland around the turn of the 20th century. He had two young daughters and his wife was pregnant with a third child. It has been speculated that Lanfray suffered from severe depression, though this is impossible to confirm as depression was not considered a medical condition at the time. It is certain however that Jean Lanfray was an alcoholic, and had been for quite some time. On August 28th, 1905 Jean Lanfray took his lunch break, which consisted of a sandwich followed by seven glasses of wine, six glasses of cognac, a cup of coffee spiked with brandy, two glasses of crème de menthe, and two glasses of absinthe. When he came home that evening, Lanfray was profoundly drunk and following an argument, shot his wife and two children with a hunting rifle. He then turned the gun on himself, but only managed to injure himself.

In the wake of this terrible tragedy, the press all around Europe latched onto one detail of the case: the absinthe. In the trial, Lanfray’s attorney based his defense on the theory that the two glasses of absinthe had driven his client mad. The defense didn’t stick in court, but it sure stuck in the newspapers and in public opinion all across Europe. Soon after, Switzerland banned the sale and production of absinthe. The United States and much of Europe followed suit over the next decade.

With absinthe culture almost entirely stamped out, most of these bans sat on the books for nearly a century. However, in the 1990s absinthe began to pick up some steam in Great Britain. Absinthe, with its strong association with the French, had never been overly popular in the UK before and therefore no ban was really necessary. As a small revival took root, people began to realize that there was no modern scientific validity to the pretenses upon which the bans were based. One by one, the bans were dropped including the US law in 2007.

There are now dozens of brands of absinthe commercially available here in the United States, some of them even produced by American distilleries. Absinthe is a unique liquor and an essential ingredient in many fantastic cocktails, and you don’t have to be a Parisian painter to enjoy the ritualistic preparation of a glass of absinthe. And yet even with the ban lifted, there remains a tremendous proliferation of misinformation about the spirit. That is something that we here at IPTB hope to help remedy with a full week of absinthe-related content. So check back often, because we’ll have new posts every day this week.

Advertisement

COMMENTS ( 1 )

posted on 01 July at 09:16

fascinating insight into a rarely understood phenomenon