Ava Helen and Linus peeking through a train window, Spring 1938.

Ava Helen and Linus peeking through a train window, Spring 1938.Pauling and the Guggenheim Foundation

Over the course of a decade reading Linus Pauling’s opinions on several Guggenheim Fellowship applicants, Henry Allen Moe, Secretary of the Guggenheim Foundation, developed a good sense of Pauling’s capabilities in judging the work and potential of his peers. At the same time, the two increasingly became friends, with Pauling visiting Moe several times while in New York and Moe staying with the Paulings during journeys to California. Their relationship during this period is nicely summed up in a 1934 letter from Moe requesting Pauling’s comments on an application. In it, he wrote

I realize the burden my questions place upon you and I am deeply appreciative of the quality of advice you give us. Whether you talk of Foundation policy or of quality in the applicant, I am delighted to get what you have to say.

In that same letter, Moe invited Linus and Ava Helen to his home for dinner.

Pauling’s increasingly close professional and personal relationship with Moe no doubt played a part in the Foundation’s 1939 offer of a four-year appointment to its Advisory Board. Pauling immediately accepted and thus joined a group containing literary scholar Marjorie Nicholson, geographer Carl O. Sauer, physicist Arthur H. Compton, and humanist Howard Mumford Jones. Moe later confided to Pauling that the Trustees had wanted to extend the invitation for quite a while, but there had been no openings. Once on the Board, the Trustees asked Pauling to re-up four more times, leading him to serve for twenty years in total.

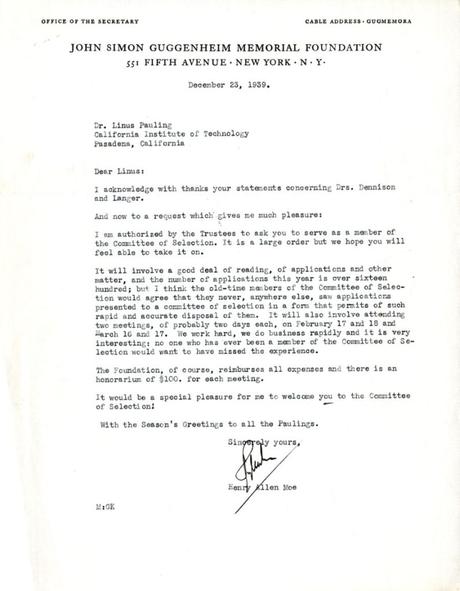

Henry Allen Moe to Linus Pauling, December 23, 1939

Henry Allen Moe to Linus Pauling, December 23, 1939Pauling’s initial enthusiasm at being named to the Board was briefly stifled when Moe told him that there would be no annual meeting that year. But something big was just around the corner. The following month, as Pauling sent his advisory reports on physics applicants, Moe wrote with more news from the Trustees. This time they wanted Pauling to be a member of the Committee of Selection, a position charged with choosing Fellows in all areas covered by the Foundation’s purview.

Moe warned that the job would require a lot of commitment and reading; and indeed, more than 1,600 applicants submitted proposals during Pauling’s first year. To make the task more manageable, Moe created summary digests of all the applications for the committee to review. Whether or not this was a necessary step for Pauling to sign on is unknown, but he was clearly excited by the opportunity and accepted the offer promptly. (Ava Helen joined in her husband’s excitement, expressing an only half-joking desire to serve as Pauling’s proxy at every other meeting.)

Unlike positions on the Advisory Board, appointments to the Committee of Selection were made for only one year, though they were renewable. This appointment calendar lent itself to a fairly consistent cycle of activities over the period that Pauling served as a member — twelve years in total, as it turned out.

First, in the fall, Moe would send Pauling a formal invitation to participate on behalf of the Trustees. The two would then begin working out the best dates for Pauling to travel to New York, since he had the longest commute of any committee member. The meetings took place in New York, generally in mid-February and again in mid-March, which meant that Pauling had to arrange for two trips across the country. With the dates set and arrangements made, Moe then sent Pauling the applicant digests by rail express at the beginning of winter. Digests also went to subject group referees for their input. Moe confirmed that the referees were very “plain speaking” because he had assured them of confidentiality.

Upon joining the committee, Pauling initially thought that he might fly to New York, but after Moe informed him that the Foundation would only reimburse him for one of the two required flights, Pauling decided to take the train instead. This mode of transport became commonplace for subsequent meetings, and as the train ride across the country took several days, Pauling always paid extra for a sleeper car, Ava Helen sometimes accompanying him. That said, during his first year on the committee – as he would occasionally over the next dozen years – Pauling realized that taking the train back and forth was simply not feasible, and he bought an airplane ticket home instead.

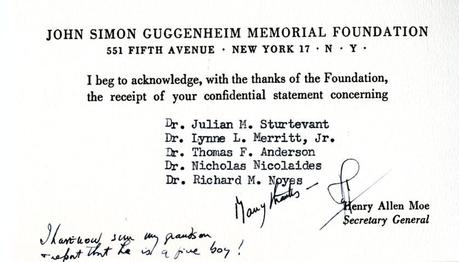

Message from Moe to Pauling indicating receipt of confidential information. Note the annotation providing an update on Moe’s grandson.

Message from Moe to Pauling indicating receipt of confidential information. Note the annotation providing an update on Moe’s grandson.During his first year as a committee member, Pauling worked through the reading prior to his departure from Pasadena, but in later years much of this work was saved for the train. Because Pauling had so far to travel and tried to consolidate his trips as much as possible, Moe sometimes sent the applicant digests to a location where Pauling was staying prior to the meeting. During the war years, this often meant mailing digests to Washington, D.C. When Pauling was invited to the 150th anniversary celebration of the University of New Brunswick in 1950, Moe arranged to send the materials to Linus Pauling Jr., then living in Massachusetts while a medical student at Harvard. But most often, if they were not sent to Pauling at home, the digests were delivered to his hotel in New York.

Moe ordered and indexed the digests according to his own preferences, which were meant to guide the Committee since they were unlikely to read all the applications themselves. In his indexes, Moe highlighted particularly strong proposals through the use of capitalized and double-spaced names, indicating a strong recommendation that they be read and considered. The only materials that Pauling was required to review were those connected to his areas of specialty, including mathematics, physics, physical chemistry, and biochemistry. Pauling could not share what he read with anyone but he was allowed to consult with his colleagues in a general way, if he desired. Pauling was also empowered to read as many cases as he liked from other areas like history, sociology and poetry.

Once the meetings had concluded, Pauling would send his travel receipts to Moe for reimbursement. Over the twelve years that he was on the Committee of Selection, Pauling’s travel expenses ranged from around $250 for each trip at the beginning, to closer to $400 at the end. These higher costs included a degree of inflation, but also had to do with Pauling flying with greater frequency. Pauling also received $100 as an honorarium for each meeting.

While this was the normal course of events, there were exceptions from time to time, mostly having to do with the calendar. In his first few years of service, Pauling was quite flexible about when the meetings were scheduled. This began to change around 1943, as his war-time commitments increased. The following year, Pauling could not wait for Moe’s usual fall invitation and instead inquired during the summer if he would be asked to serve again. Part of this request had to do with the fact that Pauling had been invited to give the Stieglitz Lecture at the University of Chicago but the university would not pay for his travel, so he hoped to make it a part of one of his annual Guggenheim trips to save costs.

Later, in 1946, Pauling found himself with so much East Coast business to attend to that he expressed a desire to cover both Guggenheim meetings during one trip, which he hoped could be scheduled within twenty-five days of each other. Because of all the work that needed to be done between the meetings, Moe told him that this was not possible.

Despite the complications of having a busy, California-based member on the Committee of Selection, Moe was well aware of the value of Pauling’s contributions. After Pauling was diagnosed with nephritis around the time of his second 1941 trip for the Committee, Moe became worried and asked that Pauling take extra good care of himself. That fall he wrote to Ava Helen, who was answering some of Pauling’s mail during his recovery, that her husband was a “first-class member of the Committee and first-class members of that Committee are very, very, very scarce.” Moe’s estimation of Pauling would remain high during the years that followed.