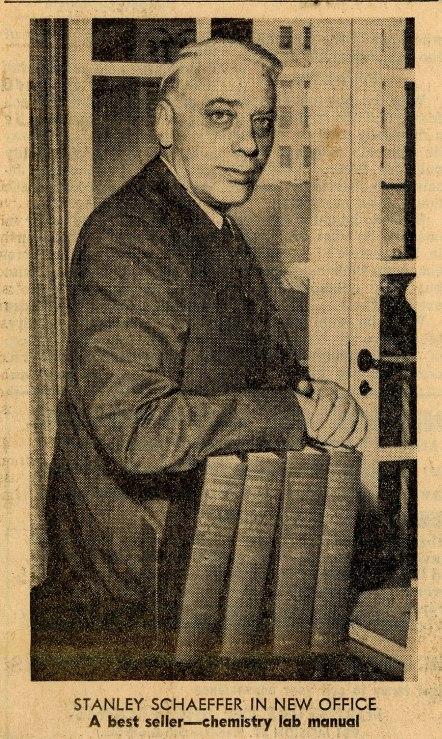

Stanley Schaefer as photographed by the San Francisco Chronicle, 1962.

[Part 4 in our series examining Linus Pauling’s relationship with publisher W.H. Freeman & Co.]

As the 1950s moved forward, W.H. Freeman & Company sought to actively build on past successes. Objective number one in doing so was expanding the number of textbooks that the company published. Objective number two for Bill Freeman was to increase the firm’s staff in order to match editorial and publishing demands.

One of the first employees that Freeman hired when he started his company was Janet MacRorie, the head of marketing. MacRorie and Freeman first collaborated on the advertising and marketing campaign supporting General Chemistry in 1947. In the early 1950s, Adam Kudlacik joined the firm as treasurer and secretary, thus beginning a lengthy tenure with the company. Harvey McCaleb also joined the team in 1953 to handle Midwest authors.

Perhaps the most significant addition to Freeman’s staff come on board in 1949, when Stanley Schaefer joined Freeman and John Behnke as one of the firm’s principal editors. The original intention for Schaefer was that he base himself in New York for purposes of recruiting and negotiating with East Coast authors, but Freeman was so impressed with Schaefer’s work that he invited him to move to the company’s headquarters in San Francisco not long after he was hired. Schaefer was pleased with the transfer and, in 1957, was promoted to executive vice-president. (He remained with the company for several decades, eventually becoming president and chairman.) With Schaefer’s promotion, another consequential hire was made when William Kaufman took Schaefer’s old spot on the editorial staff.

Though business had been been strong throughout the post-war period, by the late 1950s Freeman began to worry that the company’s competitors were gaining traction. Looking to bolster his catalog, Freeman decided to re-concentrate efforts to entice respectable authors to sign contracts with Freeman & Co. And while he continued to send outside manuscript proposals to Linus Pauling for the chemistry series that he edited, Freeman also began to query Pauling for ideas on scientific areas that did not currently have a well-written or modern textbook in circulation. He then used this feedback to pinpoint his recruitment of authors to publish within those areas.

Freeman also updated the editorial plan for the book series that Pauling was heading. In particular, Freeman began to push the idea that non-science students could be harnessed to promote what he called “the revolution in scientific education.” Likewise, because Pauling’s groundbreaking General Chemistry text had been so successful, Freeman wanted to publish more non-traditional and experimental books in Pauling’s line.

Pauling didn’t disagree with Freeman’s point of view, but he advised caution. Privately, Pauling was concerned that, in seeking to grow the company, Freeman might begin to adopt selection and recruitment policies that were employed by larger firms. Were he to do so, Pauling worried that Freeman might be tempted to sell the company if it grew beyond him. In Pauling’s opinion, Freeman was fundamental to the company’s success and this success could not continue – at least not in the same way – if Freeman allowed the company to pursue the same models as larger publishing firms.

Despite the hand-wringing, W.H. Freeman & Co. flourished throughout the remainder of the 1950s. A new milestone was reached at the end of the decade, when Freeman announced plans to open a satellite editorial operation in London. The establishment of this branch in 1960 opened new markets for the company in England and elsewhere across Europe, and did much to increase the firm’s appeal among British authors.

Bill Freeman was beginning to receive recognition for his achievements as well. In 1960 he was awarded a Doctorate of Humane Letters from his alma mater Hamilton College, and was also nominated by Pauling as California Industrialist of the Year. Though he didn’t win this award, it meant a great deal to Freeman to know that Pauling respected and admired him enough to nominate him for a prize that celebrated success through creativity and innovation.

Unsurprisingly, the company’s reputation in its hometown was quite strong. On one occasion, the San Francisco Chronicle called Freeman & Co. “a great big sensational success story,” and indeed this was so. At the time, textbook publishing was largely the domain of a handful of companies located on the East Coast. In fact, as the Chronicle article pointed out, there was only one reputable textbook publisher anywhere on the West Coast: W.H. Freeman & Co.

But amidst growth, change and strategic planning, for Freeman the mission statement remained the same. The company, he said, published “only those [books] it thinks are based on a new and advanced viewpoint.” And though the company’s mission was unchanged, its approach to publishing was becoming more experimental. Notably, as the 1960s moved forward, the firm entered into a joint venture with Scientific American to publish off-prints of older articles.

As we will see in our next post, Freeman was not on board with the Scientific American arrangement, a collaboration that emerged out of larger difficulties for the company. In fact, while at the conclusion of the 1950s Freeman could happily describe himself as director of the company but also “semi-retired,” change was very near on the horizon. Comforted for the moment by the glow of hard-earned achievement, the publisher may also have had an inkling of the troubles that would soon arise.

Advertisements