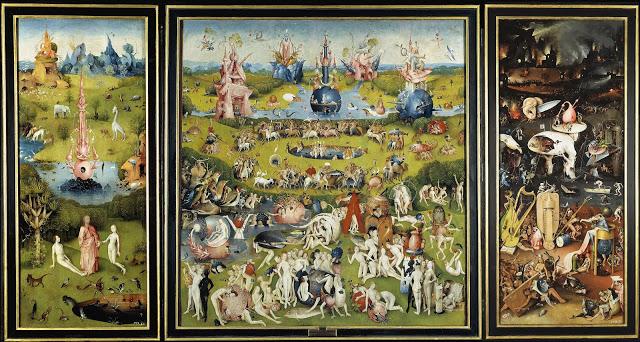

"For in the resurrection they neither marry, nor are given in marriage, but are like angels in heaven"I saw this picture in the "flesh" a few months ago in the Prado of Madrid, and two things struck me immediately about Bosch's masterpiece. One was the oriental/surreal quality of the whole work, that sense of sheer pleasure (very oriental) and joy that is derivable from sexual interaction, and, the blurring of boundaries between beings involved in such acts. The other quality was the brilliant humour and irreverence of the entire piece, very little is out of limits and sacrosanct in his depiction of our fallen humanity.

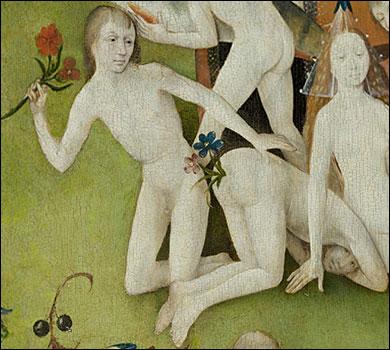

Considering the times in which it was painted it still nevertheless is really radical. The central panel, in my mind anyway, remains in visual form, one of the greatest puzzles not just in Art History, but indeed in our collective narratives as a species. On the one hand, the whole scene, hints to a fallen paradise that once may of been, a place of radical experimentation, joy and pleasure, emanating from the heart of an inexplicable creation, such Beings as these would seem to be unaware of time, limits and boundaries as we understand them, questions pertaining to the nature of creation, would likewise seem to be irrelevant to their existence of pure pleasure. Yet alternatively, it also hints, through its numerous depictions of pure excess, people copulating with all manner of beings, at an eventual limit, and even predictable boredom that could come into such an "innocent world", situated within a timeless paradise of pure bodily pleasures.

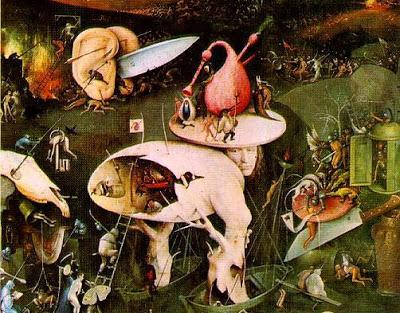

Yet, the genius of Bosch's work is that unlike so many other Artists, he never, even though he depicts the Last Judgement in the far right panel, falls into the fatal trap of morally interprating the fall and the Last Judgement in terms of people who've sinned against the world and therefore must be punished in Hell for this. He's just too inteligent an Artist too do this, instead he leaves us to ponder the mixed meanings of his work, in which there is a lingering sense that such a paradise may have had to be shattered, like a great ornate church glass window, eventually, and not out of any sense of transgression by a wrathful God, but rather out of the greater necessity born in the very notion of such a humanity itself, namely the need to give up such an imperfect paradise for perhaps a truer paradise at the end of time, that place of true intergration, of body, mind and spirit, a heavenly garden of pure delights?