When in the late summer of 1939 Hilda and Dorothy had driven Lieselotte crouched in the back of the car across the Vale of York and had come upon the woman in hair curlers under her railwayman's peaked cap struggling with the gate of the level crossing, and when little fat Dorothy had climbed out to help her, nobody noticed that a brown paper envelope, which Lieselotte had had with her since Hamburg, and which had been handed to a flustered Hilda by the woman from the refugee movement, had slipped from her lap and out of the car on to the railway line. When Hilda had driven across the line and stopped the car again to ask the way to Shields West, and the woman had said she didn't know much because she came from Hull, it had ended in laughter. Dorothy had looked round and said she wished she could give Lieselotte a sweet.

What she had in fact given her in that moment was six years of blessed anonymity and invisibility...

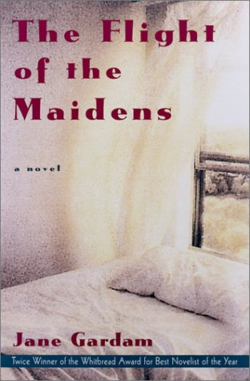

I'm fairly new to the novels of Jane Gardam, having read, and loved, three in a row less than two years ago. I've kept meaning to get back to her but this is the first time I have. Though she didn't start writing till 1971, when she was in her 40s, she has published ten novels and numerous short stories, and I wasn't sure which one to choose, so picked this one, published in 2000, more or less at random. Thank goodness, it didn't disappoint.

The Flight of the Maidens is set in 1946. As it begins, three girls are sitting in a Yorkshire graveyard, talking about their futures. They've just left school, and all three have won scholarships to university. Clever Una will go to Cambridge, pretty, insecure Hetty and quiet, plump Lieselotte to London. The novel covers the few weeks of the summer vacation, as they prepare to leave home, but also explores their pasts and their families. Lieselotte knows little of hers, having come to England on the Kindertransport and been settled with a kindly, undemanding Quaker couple. Una lives alone with her rather eccentric, strong-minded hairdresser mother, her father having committed suicide. She has a boyfriend, Ray, a romantic, political railwayman. Hetty's father, irrevocably damaged by WW1, works as a gravedigger, while her mother Kitty takes refuge in an intense relationship with the vicar and daily chats with her friends in the local tearoom.

University will change these girls, but the summer changes them first. Una and Ray go on cycling weekends to far-flung hostels, hoping for and initially failing to find the privacy that will allow them to lose their virginities. Hetty, uncertain whether she is clever enough to go to university (she thinks she only got in because she was coached by her sexless, literary, boyfriend), decides to take a pile of set books to a remote cottage in Cumbria and spend her time reading them. And Lieselotte moves first to a London flat owned by an elderly pair of warmhearted, untidy Jews, and then to California where she has discovered her only surviving relative, a terrifying ancient great aunt who plays bridge all day, and expects Lieselotte to look after her in return for a massive inheritance when she finally dies.

'We never know what the hell we're writing about', Jane Gardam has said, 'not even when the book's over'. But obviously this one's about growing up, and about going out into the world, about breaking ties and forming other ones. For Una and Hetty, the biggest challenge is the ties with their mothers. Una is strong and confident, and her mother is brave and independent. They will miss each other, but neither will make a fuss about it, and their relationship will stay strong. For Hetty it's a different matter. Her mother, fussy, clinging, over-protective, drives her crazy, and she often reacts with outbursts of anger which she regrets terribly afterwards. She is infuriated when she arrives at Betty Bank in the Lake District to find a letter from Kitty already waiting for her -- a letter she realises her mother must have written while the two of them were in the room together the evening before she left. Letters arrive every day, and she throws them under her bed unopened, as she also does with the ones that come from her boyfriend. As for Lieselotte, the circumstances of her life have made her unusually resilient in one way, but she's also emotionally withdrawn and clearly in denial about the uncertain fate of her German family, something she will finally have to come to terms with. There's some sadness, even some tragedy, for all three girls, but also a final sense of them going bravely forward into a new and exciting life.

So the story is a fascinating one, and one that will ring bells with any woman who's had a mother (so that's every woman). But there's more to Jane Gardam's books than just the plot. I love the way she writes, constantly surprising you with quirky observations and peculiar, wholly believable people, like the level crossing keeper in the quotation at the top, who will never reappear but who you'll never forget. I rather gather, though I didn't know this until after I'd read it, that this novel met with quite a mixed response. Not from me, though -- I absolutely loved it and can't wait to plunge into another one. Perhaps one of her two Whitbread Prize winners, or her Booker nominated God on the Rocks? Who knows where the mood will take me.