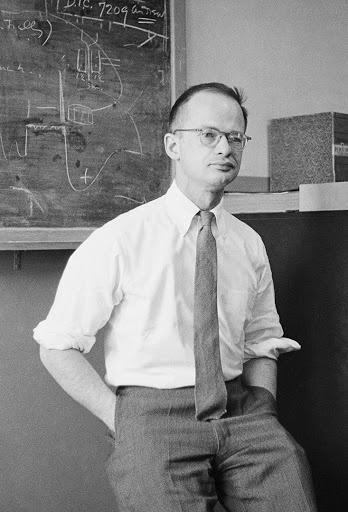

Walter Pitts

Walter Pitts[Pauling and the Guggenheim Foundation]

Linus Pauling’s roles on two John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation committees – the Committee of Selection and the Advisory Board – brought with them several responsibilities. Much of the work that he took on, including judging applications and recommending candidates from the outside, was fairly routine. In other instances, Pauling was asked to perform duties that went above and beyond those typically required of his committee colleagues. One such instance came about with the curious case of a 1945 Fellowship granted to a mathematical logician, Walter Pitts.

A brilliant, complex individual, Detroit native Walter Pitts was shuttling between studies at MIT and private sector work during the time of his Guggenheim award. At some point after beginning his Fellowship, Pitts broke a vertebra and ended up in a Los Angeles hospital. The neurophysiologist Warren McCulloch, who was working with Pitts to develop a logic of nerve activities, wrote to Henry Allen Moe, the Secretary of the Guggenheim Foundation, that Pitts was restless and wanting to leave the hospital against his doctors’ recommendations. As a salve, McCulloch hoped Moe could arrange for “some interesting young men” to visit Pitts and keep him occupied.

Moe, in turn, wrote to Pauling and asked that he look into the details of Pitts’s condition and the status of his finances. If it seemed necessary, the Guggenheim Foundation would agree to pay for Pitts’s transfer to the University of California Hospital in San Francisco, where he could interact with, and even be treated by, neurosurgeon Howard Nafziger.

By the time that Pauling had tracked Pitts down, he found that he was out of the hospital and in a cast. Pauling also learned that Pitts was suffering from a compression fracture, which was not causing too much trouble, and that his spinal cord was not damaged. Pitts made plans to visit Pauling at Caltech in about two weeks, a meeting that Pauling was looking forward to because of his interest in Pitts’s research connecting complex mathematical calculations to problems in physiology and medicine. Pauling also reported that Pitts was planning a trip to Mexico City, despite the need to continue wearing his cast for about six months. Moe was relieved to learn that the two planned to meet in person.

Shortly before the time of that meeting, Jerome Lettvin, Pitts’s friend and physician, called Pauling to ask if he knew of any places in the Pasadena area where he and Pitts might stay while Pitts continued his recovery. Linus and Ava Helen promptly began searching for possibilities and ultimately arranged for Pitts to stay in a guest apartment owned by Edward Crellin, a retired Pasadena steel magnate and large donor to Caltech’s chemistry division. The next day, Pitts called to say that a room at another friend’s place in Covina had opened up and they would not need the Crellin apartment after all. Though he was slightly confused by the situation, Pauling was not bothered.

Henry Allen Moe, on the other hand, was beginning to worry. He had only received one telegraph about the situation so far, and Lettvin had not responded to additional requests for information. Pitts was receiving a $2,000 stipend at $166 a month and, with no other resources, Moe did not think it would be enough to get by. At their scheduled meeting, Pauling was specifically charged with learning more about Pitts’s financial needs.

As it turned out, that meeting never took place. After Pitts failed to show, Pauling tracked him down anew and found that he was back in the hospital, this time for surgery related to a puncture wound on his knee that was not healing. Pauling initiated contact and Pitts once again made plans to see Pauling once he had been discharged. Pauling also convinced Pitts to submit a statement of the extra expenses that he had incurred because of his injuries. The two would follow up on these and other issues when they talked in person.

Once they had finally met, Pauling sent Moe his report. “Pitts is a strange fellow,” he confided, but “extremely able” in matters related to both mathematics and physiology. Notably, Pauling had pressed Pitts for his opinion of the physicist Nicolas Rashevsky, who had also looked to apply mathematics to biological phenomena. Pitts’s take agreed with Pauling’s, leading Pauling to deduce that he had “common sense” in addition to scholarly acumen. “Nevertheless, he is strange,” Pauling wrote, “one of the strange, brilliant people.”

From what he could tell, Pauling also felt Pitts to be recovering as expected, though he was still in a cast and limping from his knee operation. The hospital statement for Pitts’s surgery was likewise in hand, but Pitts had already made a $75 down payment and did not want to be reimbursed. Nonetheless, Pauling felt they should still follow Moe’s suggestion of providing medical funds so that Pitts could get his teeth fixed.

Happily, after all of his difficulties Pitts was eventually able to carry out his work as a Fellow, which resulted in a joint paper, published with Warren McCulloch, on neurological functions related to the perception of forms. Pitts was awarded another Guggenheim Fellowship a year later. He is remembered today as having been a major figure in the field of generative sciences who made significant theoretical contributions to areas of study including neuroscience, computer science and artificial intelligence.