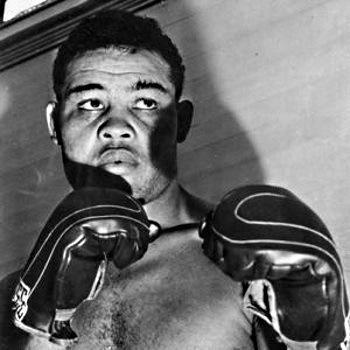

Heavyweight Champ Joe Louis

“You Can Run, But You Can’t Hide”

[courtesy Google Images]

When Lehman Brothers filed bankruptcy, its assets were only 3% greater than its liabilities.

Today, the Federal Reserve is the single largest central bank in the world. It’s assets reportedly exceed its liabilities by only 1.3%—less than half of what Lehman Brother had when if filed for bankruptcy in A.D. 2008. The Fed has much greater significance than Lehman Brothers and is operating with a much smaller “margin for error”.

The Fed’s potential for causing trouble for the US and global economies is enormous.

SovereignMan.com recently published an article with the peculiar title of “The global financial system is now resting on a margin of 1.3%.”

The article explained that,

“In 2008, the Federal Reserve’s entire balance sheet was just $924 billion. And the total of its reserves and capital amounted to $40 billion, roughly 4.3% of its total assets. Today the Fed’s balance sheet has ballooned to $4.5 trillion, nearly 5x as large. Yet its total capital has collapsed to just 1.3% of total assets.

“The Fed’s total capital corresponds to the Federal Reserve’s ‘net worth’. The value of the Fed’s assets needs to exceed their liabilities.”

That means that, on a percentage of assets basis, the Fed’s relative “net worth” has fallen by 70% in the past seven years. More importantly, insofar as the Fed’s assets now exceed the Fed’s liabilities by only 1.3%, that “net worth” is razor thin and there’s not much margin for error.

“In the Fed’s case, its liabilities are all the trillions of dollars in currency units that they’ve created, known as ‘Federal Reserve Notes’.”

I don’t necessarily agree that Federal Reserve Notes (FRNs) are the Fed’s liabilities because the Fed doesn’t redeem its FRNs. With real money, the government or bank that issued the paper currency is liable to “redeem” its paper dollars with something tangible like gold or silver. However, today, there’s no proviso for the Fed to “redeem” its FRNs with anything other than newer FRNs.

Insofar as FRNs are “redeemable” and therefore “liabilities,” they can be redeemed by the government as payment for taxes, but are mostly redeemed by the American people and peoples of the world who will trade their tangible wealth (homes, land, labor, commodities, food, resources, products, services, etc.) for FRNs. The government might redeem some FRNs as payment for taxes. The People might redeem FRNs as payment for their labor and private property. But the Federal Reserve does not redeem FRNs, so I don’t agree that FRNs are the Federal Reserve’s “liabilities”.

Even so, let’s proceed with argument presented by the Sovereign Man because it leads to a very interesting inference.

“The Fed’s assets are things like US government bonds.”

“Over the last several years during its multiple quantitative easing programs, the Fed has essentially created trillions of Federal Reserve Notes (i.e. ‘money’) and used those funds to buy US government bonds.

“In conjuring all that new money out of thin air, they created about $3.5 trillion worth of liabilities, which were offset by the $3.5 trillion worth of bonds they purchased.

“In total, the Fed’s “net worth” hardly budged.

“As a percentage of their total assets, their net worth really tanked [by 70%].”

As you’ll read, because:

1) the Fed’s “net worth” is only 1.3% of its total assets; and

2) most of the Fed’s assets are US bonds; then, it follows that,

3) the Federal Reserve is extremely vulnerable to changes in the values of its bonds.

If the market value of the US bonds held as assets by the Federal Reserve were to decline by, say, just 3%—that might be enough to overwhelm the Fed’s 1.3% positive “net worth” and thereby render the Federal Reserve technically insolvent.

“When Lehman Brothers went under in 2008, its total capital was 3% of its balance sheet. Today, the Fed’s 1.3% is less than half of that.”

The Lehman Brothers bankruptcy nearly collapsed the US and global economies. The Fed is far more important than Lehman was, but is running a much smaller “net worth”. More, the Fed’s net worth is extremely vulnerable to even a small decline in the value of its US bonds.

What might cause the value of US bonds to fall significantly?

The Sovereign Man explains:

“The universal law of bond markets is quite simple: bond prices and interest rates move inversely to one another. In other words, when interest rates go up, bond prices go down.”

Thus, if the current prime rate of 0.25% were raised even a little bit (say, to 0.50%), the market value of all US bonds would fall—including those held by the Federal Reserve.

“The Federal Reserve is sitting on $4.5 trillion worth of existing bonds, most of which they purchased when interest rates were basically zero.

“So what happens if the Fed raises interest rates? The market value of their entire bond portfolio will fall. Given the razor-thin capital the Fed has in reserve, they can only afford a tiny 1.3% loss on their bond portfolio before they become insolvent.

SovereignMan did not extend this argument further, but to me, the next inference is both obvious and crucial to understanding why the Fed has refused to raise interest rates for almost seven years.

We’ve seen the Fed do the dance of the seven veils for 80 months. Will they raise rates? Won’t they raise rates? Will they; won’t they? Is the economy strong enough to sustain a minuscule 0.25% interest rate increase—or is the economy still too weak?

Given that we’re only talking about raising interest rates by a quarter of a percentage point, the whole dilemma about whether the Fed will or won’t raise interest rates has seemed silly. On the face of it, we could suppose that a 0.25% increase in interest rates would be almost unnoticeable. If the economy is so weak that we can’t even raise interest rates by a negligible 0.25%, then the economy must truly be on life support and in need of last rights performed by an economic guru.

But, if we accept the SovereignMan’s argument that:

1) the Fed’s “net worth” is only 1.3% of its total assets;

2) most of the Fed’s assets are US bonds; and therefore,

3) the Fed is extremely vulnerable to changes in the values of its bonds—

Then, the Fed’s persistent refusal to raise interest rates makes perfect sense.

I.e., the Fed hasn’t raised the interest rate in nearly seven years because by doing so, they would reduce the market value of the $4.5 trillion in US bonds in the Fed’s portfolio.

Remember? The universal law of bonds? If interest rates rise, bond prices must fall?

That means that if the Fed raises interest rates from 0.25% to 0.50%, the market value of US bonds held by the Fed will fall. If that fall in bond market prices exceeded the Fed’s 1.3% “net worth,” the Fed would be technically insolvent and arguably bankrupt.

• God only knows what might happen if the Fed were perceived to be bankrupt. But whatever the results of a technical insolvency might be, they couldn’t be good for the US or global economies.

How much confidence could the world retain in FRNs as “world reserve currency” if the Federal Reserve were seen to be bankrupt?

If the Fed became insolvent because it raised interest rates, the value of the Fed’s fiat dollars would also have to fall significantly.

If a rise in interest rates caused the Fed to become technically insolvent, that wouldn’t necessarily collapse or kill the dollar. But it might not be surprising if the dollar’s purchasing power suddenly fell by 10%—20%—maybe more.

Further, once the Fed was shown to be insolvent, I think it would precipitate a spiraling crisis in confidence that would slowly feed on itself until—within a year or two—both the Federal Reserve and its FRNs were relegated to the ash heap of history.

In this context we can imagine why the Fed has persistently failed and refused to raise the Near Zero Interest Rate: doing so might destroy both the Federal Reserve and the fiat dollar. Since the Fed’s current 1.3% “net worth” is so small, any raise in interest rates—even by just another 0.25%—might be suicidal.

Therefore, not wishing to commit suicide, the Fed has logically and persistently refused to raise the interest rate for the last 55 Fed meetings over an 80 month period.

• For almost seven years, the Fed has justified its persistent maintenance of the Near Zero Interest Rate as being necessary to preserve and protect the US economy.

But, if the Sovereign Man’s argument is valid, the Fed’s justification is pure smoke. The Fed’s decision to hold the interest rated at 0.25% for nearly seven years is not about preserving the fragile US economy, per se. It’s about preserving the fragile Federal Reserve and the fragile FRN. If the Fed were to double the interest rate from 0.25% to 0.50%, and if the result was a loss of over 1.3% of the current perceived value of US bonds, the Fed might be destroyed.

The Fed is not “here to help you”. They Fed is here to help itself.

• If this conjecture is correct, one way the Fed could theoretically raise interest rates would be for the Fed to first acquire additional assets (other than bonds) that would increase the “margin” between its debts and assets from 1.3% to something sufficiently higher (4.0%?) to ensure that the Fed wouldn’t be plunged into (or near to) insolvency by raising the interest rates.

But how can the Fed increase its assets, without also increasing its debts? So long as increased assets result in corresponding increased debt, the 1.3% “net worth” will remain small, marginal and dangerous.

• Another theoretical solution might be based on the common belief that the Fed could simply “spin” enough currency “out of thin air” to purchase more assets or simply add that currency to its portfolio to create more positive “net worth”. But the idea of the Fed “spinning currency out of thin air” is not quite true.

Contrary to popular belief, the Fed can’t merely print more currency and spend it into the economy. So far as I know, all of the Fed’s paper dollars are all loaned into circulation. When the Fed prints more currency, that currency must just lay there, dormant and unused until some third party borrows it. Unless the Fed changes its policy, the Fed can’t inject more freshly-printed dollars into the economy or into its portfolio, unless some third party is willing to borrow those new Federal Reserve Notes.

Q: Who would be able and willing to borrow FRNs from the Fed

A: The US government.

Q: What would the US government use to “pay” for the some freshly-spun FRNs?

A: Freshly-printed US bonds.

Q: But, wouldn’t the value of those new US bonds would fall as soon as the Fed raised interest rates?

A: You betcha.

Q: Doesn’t that mean that lending more FRNs to the US government in exchange for for more US bonds can’t help increase the Fed’s “net worth” and is therefore a pointless strategy?

A: Seems so.

• If the Fed can’t escape the 1.3% “margin for error” by purchasing more assets or lending more FRNs, another way that the Fed might theoretically be able to raise interest rates is to first sell off some of the Fed’s “toxic assets” to increase the 1.3% margin to avoid the insolvency that might follow a rise in interest rates.

But, like the US bonds in the Fed’s ledger, its “toxic assets” have a current perceived value that must be maintained for the 1.3% margin to be retained. Given that much of the Fed’s “toxic assets” were purchased during Quantitative Easing, could the Fed sell any of its “toxic assets” without admitting that they are no longer worth their purchase price and presumed “face value”? If the market value of the Fed’s toxic assets fell, that could also cause Fed liabilities to exceed Fed assets, destroy the 1.3% “net worth” and push the Fed into insolvency and even bankruptcy.

• There’s another hypothetical possibility for increasing the Fed’s 1.3% “net worth”. Let’s suppose that the Fed owned four thousand metric tons of gold which were counted as part of its assets. At current prices, that gold would be worth about $40 million per ton or $160 billion total.

Let’s suppose that the Fed caused the price of gold double to, say, $2,300/ounce. The value of those 4,000 hypothetical tons of Fed gold would rise from $160 billion to $320 billion. Would the “extra” $160 billion in assets be enough to increase the 1.3% “net worth” enough to allow an increase in interest rates without killing the Fed and the FRN?

I don’t know.

What if the Fed caused today price of gold to rise by a factor of 4 to, say, $5,000/ounce? The value of the 4,000 hypothetical tons of gold would rise from $160 billion to about $700 billion. The Fed’s assets would be increased by over $500 billion. Now we’re talkin’. That should be more than enough to increase the 1.3% “net worth” to a level that could withstand a rise in interest rates from 0.25% to 0.50% or higher.

But, does the Fed own 4,000 metric tons of gold? Not according to the Federal Reserve. It gave all of its gold to the federal government back in A.D. 1934. Thus, this hypothesis is mildly interesting but impossible.

• One last crazy hypothetical: maybe some billionaire “angels” (maybe the American people??) would simply donate $500 billion to the Fed’s balance sheet. A gift of that magnitude would solve the Fed’s 1.3% problem. But, on reflection, I’d have to say . . . . hmm . . . prob’ly not.

• Conclusion: The Fed is screwed. It can’t purchase more assets to increase the 1.3% margin of error. It can’t sell off its toxic assets without also crossing the 1.3% margin of error. It can’t lend more FRNs out, except in exchange for government bonds. And it can’t raise interest rates without causing the value of its US bonds to fall—perhaps enough to overwhelm the 1.3% margin of error.

If the Fed’s balance sheet was populated with a diverse variety of assets (stocks, US bonds, foreign bonds, cash, gold, etc.), if it raised interest rates, the value of its US bonds would fall, but the remainder of its investments would presumably remain largely unaffected. The Fed’s 1.3% “net worth” might be hurt a little, but not too much. The Fed would still have room to maneuver, if it cared to do so.

However, it appears that by lending $4 trillion to federal government, the Fed’s balance sheet became unbalanced with too many ($4 trillion) US bonds. Because the Fed’s assets are almost entirely US bonds, and has such a small “net worth” (1.3%), the Fed can’t raise interest rates without reducing the value of their $4 trillion in bonds and plunging the Fed, itself, into insolvency and bankruptcy.

The Fed is caught in a conundrum that not even Solomon could resolve. They are truly “darned if they do and darned if they don’t”.

Implication: For now, the Fed is unlikely to raise interest rates and will avoid doing so as long as possible.

Nevertheless, sooner or later, the Fed—seeing no escape from its predicament—will probably say “screw it,” raise interest rates and risk the resulting insolvency and/or bankruptcy.

If the premises and arguments presented by Sovereign Man–and the inferences that I draw from those arguments—are valid, the Fed is ensnared in a web of its own creation where it can’t create more liabilities, can’t buy more assets, can’t lend more currency to the US government, and can’t increase the interest rate without destroying itself and the FRN.

If all that’s true, who thinks that the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates this next December?

• On the other hand, if the Fed can’t raise interest rates, who’s now willing to consider the possibility that the Fed might soon impose negative interest rate that would raise the price of bonds, increase the perceived value of the US bonds held by the Fed as assets and thereby at least increase the Fed’s 1.3% “net worth”?

Remember the universal law of bonds? When interest rates go up, bond prices go down. When interest rates go down, bond prices go up.

Most people have presumed that zero is the lowest limit for interest rates. Therefore, the Fed’s 0.25% interest rate is so “near” to zero that they can’t go any lower. Therefore, the market price for bonds can’t go any higher and the Fed’s assets can’t be increased enough to add another few percent to its 1.3% “net worth”/“margin for error”.

But—not to worry. In our brave new world order of debt-based currency, it’s mathematically possible to impose a negative interest rate that’s even lower than the current, positive 0.25%. It could even be lower than zero percent. It could be a minus, say, 2%. Or minus 4%. Or even minus 10%!

Several banks in the EU have toyed with negative interest rates on bank deposits. The Federal Reserve has considered negative interest rates as a potential tactic.

Given the universal law of bonds (interest rates and bond prices move inversely), a negative interest rate should increase the market value for US bonds. If the Fed could increase the market value for its $4 trillion in US bonds, it could also increase that “net worth”/ “margin of error” of 1.3% to, say, 2.0% or even 4.0%.

Thus, by using negative interest rates, the Fed could still pull another trick or two out of its sleeve. It could still “do something” and thereby avoid being dismissed as impotent and irrelevant.

Even so, the Fed’s objective is to not merely find a way to “do something” but find a way to raise interest rates without causing the price of US bonds to fall. In other words, the Fed is looking for a way to break the “universal law of bonds”. The Fed needs to raise interest rates without causing the market price of bonds to fall.

Probably, that can’t be done—not even in the irrational, crazy world of a debt-based monetary system.

Which brings me back to my previous conclusion: The Fed is screwed. By purchasing several trillion dollars’ worth of US bonds, they’ve overloaded their balance sheet with US bonds, and apparently painted themselves into a 1.3% “net worth” that leaves them no room to maneuver; no room to raise interest rates by even 0.25%.

So, now what?

(I can imagine why Janet Yellen lost her ability to speak during a recent one-hour presentation. She had to leave the stage without completing her speech and sought emergency medical attention. Apparently, she was alright. But, I’d bet her “spell” was caused by the stress of knowing there’s no way out. The Fed has no more “tricks” and no place to hide. Facing that reality must be sobering, even staggering for someone in Yellen’s position.)

• World heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis once told an opponent, “You can run, but you can’t hide.” In other words, once you step into the ring, there’s space to run for a while, but there’s no place to hide. Sooner or later, the champ will catch up with you, and then it’s lights out.

The Federal Reserve made a huge, potentially lethal mistake when it “stepped into the ring” in A.D. 2008 when “Helicopter” Ben Bernanke decided to save the US from an economic depression. By committing itself to prevent a Greater Depression, the Fed meddled in problems that were too great for it to solve. In doing so, the Fed may have jeopardized its own survival.

The Fed’s been “running around the ring” ever since with a Near Zero Interest Rate. But it can’t hide from the heavyweight champ (reality). Sooner or later, reality will catch up with the Fed—and then it’s lights out.

Sooner or later, we’re going to have the economic depression that we should’ve had seven years ago. There’s no real surprise in that prediction. Everyone’s understood for several years that all the Fed was doing was “kicking the can down the road,” buying more time, and postponing the moment when we finally surrendered to an overt depression. Well, perhaps that moment is finally getting pretty close .

But, there is one surprise in all this: It appears increasingly likely that before the US economy slide into the next overt depression, we just might see the Federal Reserve expire in insolvency and bankruptcy.

If that were to happen, could the fiat dollar survive?

If not, what then?

Do we live in “interesting times”?

Ask Janet Yellen.