Photo courtesy of iStockphoto.

How much is money worth? This might seem like an odd question since we tend to measure the worth of things in terms of money. If I am willing to purchase a particular book, say a book about economics, at the cover price of $25, then it is easy to recognize that the book has a value of 25 dollars. However, the suggestion that $1 has the value of 1 dollar is tautological and uninteresting. Neither does it help much to say that $1 is worth 1/25 of the cover price of the particular book about economics, or any other arbitrary good or service for that matter, since this gives us too many values with which to measure by. We could measure money in terms of gold, but with the recent run up in gold prices this would seem to indicate that money should only be worth a fraction of its value a few years ago, yet the price of a particular economics book can likely be bought for roughly the same price it would have fetched then. Even focusing on gold prices will not help to illuminate the value of money it would seem, so perhaps we are just relegated to having many different values measured in any number of commodities. Money has no true or absolute value.

Shortly before I was born in 1976, America left the gold standard under President Nixon, when the value of the dollar had been pegged to a specific quantity of gold, and could be redeemed in gold, but alas not since I have been alive. We are now on a fiat currency system, along with most nations of the world, and this means that our money is no longer pegged to anything of intrinsic value, and the value of the dollar is based on the full faith and credit of the American tax payer instead. Legal tender laws make acceptance of paper dollars, or electronic dollars, a compulsion for those who wish to sell products in America. You could say that our currency system is faith based. The dollar is a social institution that has value because we have endowed it with value through our trust that it will serve as a medium of exchange the next time we need to purchase something.

The value of one US monetary unit, one dollar, has changed over the years, steadily losing its value, with about a 75% loss of value since I was born in 1976. I’m sure most people have heard a grandparent or elder reminisce about the price of a soda, costing only a nickel, or a penny, or something like that, back when they were a kid. Or maybe you have witnessed rising prices yourself. Either way, we are all generally aware that dollar inflation has led to higher prices over time. If you are a Ron Paul supporter, as I used to be, then you might even consider this inflationary situation to be tax on your wealth. If you are holding a fixed quantity of dollars for a certain period of time, and the prices for things you want to buy in the future rise in that same time, then it’s like you are paying a tax on holding your money. Of course, if you earn a return on your money that is greater than the inflation rate, and your income also increases faster than inflation, then your standard of living increases because the dollars you hold and earn have grown faster than the prices you must pay.

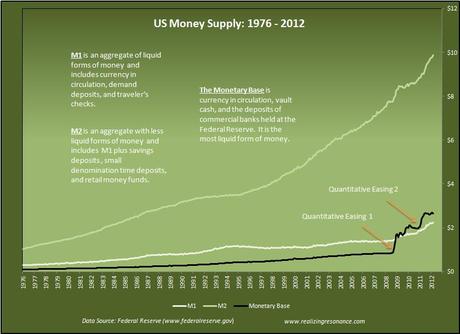

The general price level, as measured by something like the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or the GDP Deflator, is affected by the quantity of money in an economic system. The quantity theory of money suggests that rising prices over time is the result of a growing supply of dollars over time. Monetarism, the modern analog of the quantity theory of money was popularized by the Chicago School economist Milton Friedman, and can be summarized by his famous claim that, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.” If the money supply expands faster than is needed for the ongoing economic growth then the general price level will rise in an economy. In the US the Federal Reserve (Fed) is the institution charged with regulation of the money supply and price stability, but they are also mandated to address unemployment. Many people are concerned about the Fed’s increases of the money supply in order to address the 2008 Financial Crisis and the Great Recession, with particular animus aimed at the Quantitative Easing programs. The fear is that this easy money will lead to high and damaging inflation. Below is a chart of the growth in the US money supply from the year I was born until 2012.

Click on chart for larger view.

Money has different measures, with a few of the most used shown above. M1 is the stock of money that includes all the coins, cash, and traveler’s checks in circulation, plus demand deposits in checking accounts. M2 includes M1 plus additional forms of less liquid money, such as savings deposits, small denomination time deposits, and retail money market funds. I did not include M3 or MZM in the chart above, aggregates which include even less liquid components. It is a controversy for conspiratorial sorts that the Fed stopped publishing M3 in 2006. As you can see by the chart above, M2 is much much greater than M1.

The Monetary Base (MB), also called high powered money, is the stock of money that is more or less under the Fed’s control, and this is the total cash and coins in circulation, the cash in banks vault’s, and bank reserves held at the Fed. The Fed controls MB by Open Market Operations (OMOs), which is a process whereby a central bank produces new money electronically, by bringing it into being to purchase debt securities, mainly US government treasuries, but also mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in recent years. The Fed adds money to the banking system and assets to the its balance sheet which it must later sell back to the market in order to retract the new money it has supplied. The chart above shows the Fed’s recent increase to MB since 2008, in two rounds of infamous QE1 and QE2. It is interesting to note that this has pushed MB above M1, suggesting that much of the Fed’s new money creation has not made it into circulation.

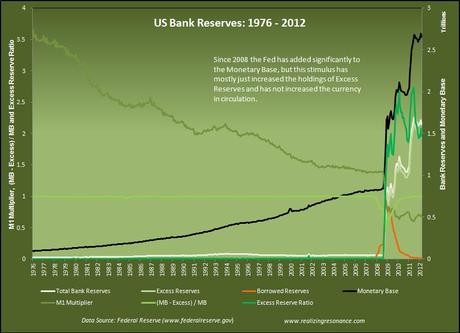

Click on chart for larger view.

The Fed has tripled the Monetary Base since 2008, but the currency has only increased 33% in that time. The unprecedented monetary stimulus has mostly sat idle in Excess Reserves, which have increased from just under $2 billion in August 2008 to $1.5 trillion in March of 2012. The chart above illustrates the historical significance of the Fed’s monetary policy, at least in my life time, but it also shows that the easy money has by and large not made it out into the economy so far. This is the problem of pushing on a string. When the Fed wants to tighten monetary policy it tends to have the direct effect of slowing economic activity by removing money from circulation that was otherwise being used productively, but when the Fed eases money it can only make more money available for banks to lend. Banks are much more risk adverse and have less opportunity for lending through depressed demand, so it should not be too much of a surprise that the massive amount of new money has not found a use for which banks and borrowers can agree on. When you pull on a string it becomes taught easily giving you easy leverage, but when you try and push on a string it goes limp, adding slack (liquidity) but no direct leverage.

Has the devaluation of the dollar resulted in a lower standard of living in America? This is the fear over monetary stimulus and inflation. Between 1976 and 2007 the Monetary Base, M1, and M2 grew by 362%, 571%, and 737% respectively, while the CPI grew by 264%. So the monetary expansion in this time has coincided with inflation, but the inflation rate has been less than the money growth rate. At the same time, real GDP grew at 157%, the number of households grew by 58%, so real GDP per household has also risen. Real incomes for the lowest fifth of income earners increased by 13%, while income for the middle fifth of earners rose 22%, and the lowest income limit of the top 5% of earners rose 53%, demonstrating that the standard of living has increased for every income class since I was born in 1976. See the chart below for the average annual rates of change in the money stocks, inflation measures, and real GDP and incomes.

Click on chart for larger view.

I am not worried about inflation in the near term, because the money stimulus from QE1 and QE2 has not made its way into the general economy yet. The inflationary process of too much money chasing too few goods can only really work if the money actually chases the goods, and right now the money is sitting still. When the excess reserves start winding through the economy I will expect prices to rise a little faster, and this process bears monitoring. Inflation has not been the biggest concern in the general public in the last few years, with the focus on unemployment and government debt, but gas prices have recently been rising alarmingly.

I would contend that most people experience money illusion. That is they tend to think about the value of their money in terms of nominal dollars, and would not consider their own rising income to be merely an inflationary effect. Money illusion makes it difficult for people to accept a reduction in wages for the same amount of work even when the market prices for goods and services have fallen by an equivalent amount. Money illusion means we tend to forget that a dollar has no absolute value. It feels better to have your wages rise by less than prices than it does to have your wages falls by less than prices, because our experience of wealth is more existentially directed toward our nominal income over external prices.

I don’t think that money illusion is absolute, people also exhibit rational expectations and money neutrality to some extent, by reacting to the expected future increases in prices, but this actually requires a certain level of economic and finance awareness, and in times of moderate inflation over long periods of time the populace is content and has a high propensity to money illusion. However, at higher rates of general inflation, or inflation in key prices such as gasoline and food, the public develops rational expectations and emotional frustrations at the quick loss of value in their money. Perhaps reading an article like mine helps to remove the illusions a little.

The changing value of money is interesting to ponder, and for some people it is a phenomenon that leaves them very uneasy. It is unnerving to realize that your money has no intrinsic value. I am not too worried about fiat money myself, after living in the world of finance and studying monetary policy, the demystification of money has left me with an appreciation for an elastic currency. I do worry that we have ventured into uncharted territory with our money supply in recent years, but I believe that the monetary authorities have good intentions and will maintain a commitment to price stability. Inflation has been a part of my life since I have been living, and I expect this to continue. As long as it is low, steady, and predictable, and as I long as living standard increase in the future, I am ok with moderate inflation.

Jared Roy Endicott