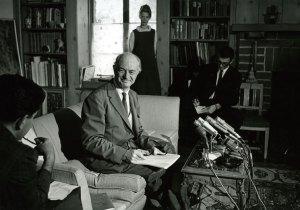

Pauling at his living room press conference, October 1963. Image credit: James McClanahan.

[Ed Note: This is part one of a six-post series examining Pauling’s association with the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions.]

In October 1963, just after it was announced that Linus Pauling would receive the Nobel Peace Prize, a press conference was held in the living room of the Paulings’ home. Pauling naturally spoke of his happiness with the Nobel committee’s announcement but he also caught the media’s attention with some news of his own: he intended to take a leave of absence from the California Institute of Technology in order to resume his work in science, peace and medicine at the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions (CSDI) in Santa Barbara, California.

The news came as a shock to most of his colleagues who were unaware of Pauling’s decision to leave after more than four decades of historic achievement at Caltech. By the time of his announcement however, Pauling had already arranged for the research currently under his supervision to continue until completion while he was in absentia. And though he didn’t come right out and say it, Pauling’s leave of absence effectively marked his resignation from Caltech.

Pauling’s decision was radical not only because he was leaving the institution where he had worked for forty-one years, but also because the CSDI was a completely different institution. Where some, like Pauling’s biographer Thomas Hager, could describe Caltech as “a monastery devoted to science,” the CSDI was, in the words of the center’s director Robert Hutchins, an “educational enterprise established by the Fund for the Republic to promote the principles of individual liberty expressed in the Declaration of independence and the Constitution of the United States.” Indeed, the CSDI was essentially a think tank that sought to study the effects of democracy and constitutional rights on modern institutions such as corporations and labor unions – a far cry from the hard science that Pauling was used to at Caltech.

Pauling hoped that his time at the CSDI it would enable his collaboration with neighboring institutions, such as the University of California schools, to perform scientific research, while simultaneously contributing to the development of ideas on world peace at the center. Pauling joined the center because he believed that science should be used to address social issues and to offer solutions to the problems facing society.

In the letter of resignation that he wrote to the leaders of the California Institute of Technology, he expressed his desire to continue his work at the CSDI because he wished to incorporate world affairs into his study of science and medicine. In this, Pauling was illustrating the degree to which he was prioritizing world affairs at this point in his life. In a letter to James Higgins, however, Ava Helen Pauling expressed concern that her husband would find the CSDI “too superficial,” a statement that would prove prophetic.

Wall Street Journal, Dec. 17, 1963.

In his fight against the use and propagation of nuclear weapons, Pauling became one of the world’s most prominent advocates for the test ban treaty that was ultimately signed by the United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union in 1963. The treaty limited its scope to banning nuclear explosions in the atmosphere, outer space and under water, but nonetheless marked a major turning point in the short history of the nuclear age.

Pauling was roundly criticized for his activism against nuclear testing. Many saw his efforts as hindering the strength and effectiveness of the U.S. military. In a 1960 article published by the Arcadia (California) Tribune, Pauling was introduced as a professor at Caltech and then accused of being an un-American communist. This example was only one of many instances in which Pauling’s professional life and the institution for which he worked for were placed in an unflattering light due to resistance to his personal views on world affairs. Trustees at Caltech took note, and as Pauling’s prominence grew, his relationship with the Caltech power structure steadily eroded.

Though Pauling obviously enjoyed a wide range of supporters as well – including the Nobel committee -media criticism, especially in the U.S., continued to intensify with the increased attention brought about by his award.

On December 17, 1963, just days after Pauling was awarded the Nobel medal, The Wall Street Journal questioned the committee’s understanding of Pauling’s views in an article titled “Pauling and Peace: Questions Linger.” The opinion piece suggested that the Nobel selectors had overlooked the significance and need for the threat of war in stopping “the cold blooded calculations of dictators like Khrushchev and Mao Tse-Tung” and that this was reason enough for “the vast majority of the American people” not to hail their compatriot for having been awarded a second Nobel Prize.

Robert Hutchins

At the time that Pauling received the Nobel Peace Prize, the most welcoming and supporting environment for his work seemed to be the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions. In a letter to Pauling dated October 17, 1963, Robert Hutchins, the center’s head and a past president of the University of Chicago, gave Pauling his full support and noted how closely aligned their views and goals were, so much so that their most recent publications had similar titles. Hutchins saw in Pauling a potential candidate to take over the center’s program of research in medicine, which was still in its nascent form at the CSDI, to say nothing of the added impact that his mere presence would immediately make upon the center’s profile.

In Pauling’s statement to the press concerning his move to the CSDI, he expressed excitement at the idea of working in an environment where he was already familiar with many of his new colleagues and could more freely choose which areas to focus his studies. Indeed, “increased freedom of action” was one of the main points of emphasis in his statement. It would seem then, that the two main reasons why Pauling was specifically attracted to the CSDI were the freedom to focus on the relationship between peace and science, and the support that he was receiving from his colleagues at the Center. With the CSDI, Pauling hoped to link his ongoing research in science, peace and medicine to the larger issues facing the political systems and social institutions of his time.

Despite the benefits and possibilities that the Center seemed to promise, Pauling knew that his work would, by necessity, become increasingly theoretical rather than experimental. Back at Caltech, Pauling’s many years of research, experimentation and funding had allowed him to amass important, and expensive, apparatus for his laboratory. The CSDI, on the other hand, had hardly even dealt with the sciences and its research in medicine had not yet included any experimental work. While trading Caltech for the CSDI was not the most expedient move for Pauling’s scientific work, it did seem to give him the freedom to focus on the matters that he valued the most during this period of his life. And so it was that, in the 1964, Pauling ventured into uncharted waters.