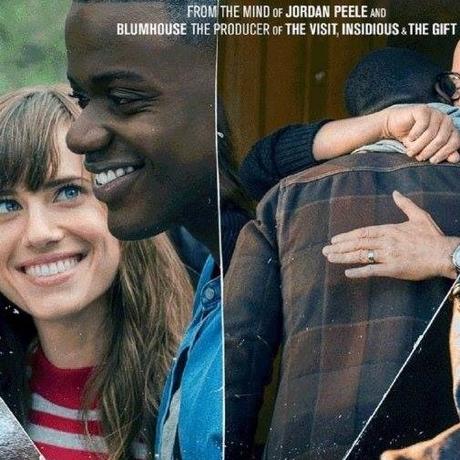

‘Get Out’

*Spoiler Alert*: This review contains details about the plot of the movie.

The film Get Out opens on a single shot that, just like the film as a whole, manages to brilliantly capitalize on horror tropes to illuminate the terror of racial stereotypes and racism. Terror in suburbia is a staple of the horror genre—a staple Get Out immediately subverts by opening on a masked figure stalking an unwitting victim—a black man. The shot is followed immediately by a credits montage set to “Redbone” by Childish Gambino—a song that recounts a sinister and manipulative dishonest relationship and warns the victim to “stay woke,” and in turn foreshadows the relationship at the center of the film. This artful scene is just one of many that prove Get Out to be one of the most necessary and captivating films in recent years.

Get Out revolves around a young, African-American man named Chris Washington, his Caucasian girlfriend, Rose Armitage, and their trip to Rose’s parents’ lakefront estate in upstate New York. Despite Chris’ apprehensions about meeting her family—“Do they know I’m black?” he asks Rose before meeting them—the couple ventures out of Brooklyn and toward the secluded manor of the Armitage home. What follows is a horror film that differentiates itself from the usual jump-scare, teens-in-danger tropes of the genre by seamlessly infusing unique racial commentary into the narrative. The sly, almost psychotically understated utilization of micro-aggressions incorporated throughout director Jordan Peele’s masterful film heightens the humor and discomfort at the heart of the film’s slow-burning path to an ultimately paralyzing sense of dread.

Although the film eventually twists itself into a psychological thriller, it starts as an exploration of the pitfalls of a modern-day, interracial couple. Once they arrive at Rose’s family’s home, Chris meets her alarmingly polite parents—a neurosurgeon father and hypnotherapist mother—who guide Chris through the house, referring to him as “my man,” immediately referencing Barack Obama, Jesse Owens. Chris also gets to know Rose’s brother, who is nauseatingly disconcerting: he gets drunk at the family dinner, and, speaking in a slurred voice about Chris’ “beastly potential,” attempts to put him in a headlock.

The true motives of the Armitages become particularly clear at a party halfway through the film. Except for one Japanese partygoer, and three other black people, all of the family friends the main character meets are white. Two of the black characters work in a zombie-like manner for the Armitages, while the third, a party guest named Logan, acts disturbingly quaint, with a sedated tone of voice, and overall obliviousness to Chris’ references about Logan being another black person. Chris, looking for solidarity with Logan, extends a fist for a pound, only to be met by Logan’s hand looking for a handshake.

It’s at this same party that the true horror underlying this narrative becomes evident. As Rose parades Chris around the party, each interaction with each new guest becomes more worthy of a head-tilt or side-eye than the last. Chris is asked about Tiger Woods, felt up by an older woman, who inquires as to whether or not the stereotype of well-endowed black men is true, told that his skin is “in fashion,” and even asked if he thinks that being black gives him an overall advantage or disadvantage in the world. It eventually becomes clear that the Armitage family aims to insert the consciousness of their white friends into black bodies, to exploit the physical benefits of the African-American vessel—to run faster, satisfy their wives in bed—while still maintaining their Caucasian self entirely. These guests prod and interview Chris as a way to ascertain whether or not they should bid for his vessel. They knowingly plan to strip a human from his body save for a piece of consciousness that remains—which acts as an allegory for slavery. This also essentially articulates what cultural appropriation is: superficially exploiting another culture, their fashion, clothes, bodies, etc., without acknowledging or honoring the grander institutions from which these now-bastardized concepts were created.

The most masterful part of Get Out, however, is arguably the way POCs’ lived realities of microaggressions and racism are represented in the intricate construction of dialog. For example, while drunkenly talking to Chris over dinner, Rose’s brother refers to Chris’ “genetic makeup” and potential to become a beast. The father refers to black mold in the basement, where it’s later revealed black moulds are made ready for white consciousnesses. When Chris tries to take a picture of the other black partygoer, Logan, the flash briefly releases him from his bondage long enough for the real Logan—a guy named Andre—to resurface and plea that Chris “get out!”—seemingly a commentary on the use of cellphone footage as a way to document atrocities perpetrated against black people.

But while the bulk of the film fuses comedy with these terrifying racial nuances, the film ends in pure terror. Bloodied, Chris finally escapes the house. He is kneeling over Rose’s bleeding form—the result of a struggle for his own freedom—when his face is illuminated with red and blue lights. The mountains of evidence to which the audience is privy, and that aren’t even necessarily hidden in the world of the film, are still invisible to the eyes of the law. The audience is left with a gobsmacking mouthful of reality: our hero is going to die because he’s black in this situation. It’s almost like a mini-horror movie at the end of the main film.

As a black male, I can attest to the rising company of doubt and nerves that manifest in my stomach when meeting the parents and families of significant others whose white daughters have chosen me as their partner. The movie articulates that particular fear—not of racism or intolerance, per se, but of how the taxing it is to prepare for these family members to make misguided attempts at relating to you—and othering you in the process. The parents blindly gush about Obama, or call you “my man”; they try to appeal to you as someone living the “black experience,” instead of just someone who is dating their kid. It’s a misguided and ultimately insulting extension of an olive branch. Obviously I’ve never been hypnotized via teaspoon, but Get Out hits a lot of personal beats and nerves in the best way possible.

The affecting pointedness of this film’s commentary on racism is as important as the fact that a black-led, black-directed horror film is one of the top films in the nation, and is quickly being cemented as a horror classic. Get Out proves that uncomfortable stories about marginalized people can exist in genre films and in pop culture at large without being niche or overlooked. Get Out isn’t a movie that will make you check under the bed, nor have you turning the lights on as you move about your house at night, but it does inject enough novocaine into your spine and extremities to infest your body with a numbed paralysis of unease and dread.