I thought there wasn't much more damage that could be done to me that hadn't already been done. You get hardened by life knocking away at you since you were old enough to feel heartsore, but then comes a knock that's bigger than anything you've experienced so far and you realize just how soft you are. How soft you'll always be.

I thought there wasn't much more damage that could be done to me that hadn't already been done. You get hardened by life knocking away at you since you were old enough to feel heartsore, but then comes a knock that's bigger than anything you've experienced so far and you realize just how soft you are. How soft you'll always be.

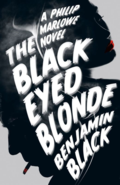

Philip Marlowe in typically self-reflexive mode, here towards the end of Benjamin Black's extraordinary piece of literary ventriloquism. Dead writers are being revived at an alarming rate these days, some more successfully than others. I'd just about decided to call a halt to my own reading of them when this came my way and oh how glad I am that it did. I'm a great admirer of Raymond Chandler and started this novel with some trepidation -- so many writers of hard-boiled detective fiction have tried to follow in his footsteps, but none has really matched up, for me at least. I needn't have worried, though. Benjamin Black -- who is, of course, the Booker prizewinner John Banville -- has succeeded astonishingly well, so much so that I almost had to keep reminding myself that I wasn't reading a newly discovered Chandler. Banville is noted for his superb use of language, and here he puts that to use so well that I couldn't find a single jarring note.

The Black-Eyed Blonde takes place after the end of the last Marlowe novel, Playback, so sometime in the late 1950s. In that novel, Marlowe has found himself more or less engaged to the wealthy Linda Loring, but here she has gone to Paris and he is alone, world-weary, drinking and smoking too much, waiting for something to happen. And something soon does. Into his office comes the beautiful black-eyed blonde of the title -- Clare Cavendish, the unhappily married heiress to a perfume business -- who wants him to trace her lover, one Nico Peterson. Things are rather complicated by the fact that Peterson has been pronounced dead after a car accident, but Clare has spotted him walking down a street in San Francisco.

Needless to say things soon spiral off in various dangerous directions, and Marlowe encounters dodgy country-club owners, murderous Mexicans, and drug-addicted youths, and meets again with friends and enemies from earlier novels. He gets wrongfully arrested, beaten up, seduced and then dropped by the beautiful Clare, drugged with a Mickey Finn. He waits around a lot, but is resigned to it: It's part of the story of my life, sitting in cars late at night with stale cigarette smoke in my nostrils and the night birds crying.

Clearly knowing and loving Chandler could have been a disadvantage but turned out to be a bonus. So does this mean this novel is only for people who know the genuine article? I'd give that a resounding no. It's a great crime novel by any standards, with many twists and turns, and I did not guess the denouement -- in fact if anything the plot is a little clearer and easier to follow than that of some of Chandler's early novels. So I'd recommend it to anyone who loves vintage crime and I suspect if you read it without knowing the originals, you'll be turning to them straight away because you'll be greedy for more of the wonderful one-liners and more than anything for more of Philip Marlowe, introspective, ironic, sensitive, intelligent and one of literature's greatest creations.

Let's leave you with one of his typically thoughtful observations, this one of Peterson's sister:

It turned out Lynne had been a dancer and worked around the clubs in Bay City. I know a bit about that kind of life, the grift and the grind of it. I could imagine how it had been for her -- the guys with curly hair on the backs of their hands, trying to pore you all the time, the night managers who applied their own conditions of employment, the drink and the drugs, the bleary late-night weariness and ash-coloured dawns in cheap hotel rooms. I had liked her, the little I'd seen of her -- she deserved better out of life.