From the years 1960 to 1968, Linus Pauling either threatened or actually instigated several libel suits against various newspapers and media outlets throughout the country, demanding retractions and financial compensation for defamatory statements issued about him. The damaging statements usually stemmed from Pauling’s hearings before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee in 1960, during which the inquisitors grilled Pauling about his activities in the peace movement, especially his 1958 nuclear bomb test petition, and repeatedly implied that he was a communist sympathizer.

Pauling was not a communist and, in fact, had led a large research effort on behalf of the U.S. war effort during World War II, work for which he earned several commendations, including the Presidential Medal for Merit. So naturally, Pauling was very frustrated when newspapers around the country began to question his loyalty to the US, and he became increasingly alarmed as his reputation was attacked amidst the heightened tensions of the Cold War era.

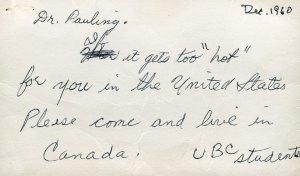

One of the first newspapers to provoke legal action from Pauling was the Bellingham, [Washington] Herald. In late November and early December 1960, shortly before and after Pauling gave a talk at Western Washington College, the paper published five letters to the editor attacking Pauling. The letters contained factually incorrect information, such as the suggestion that Pauling had appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee (rather than the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee) and that he was a communist. The letters also accused him of other communist-related activity that had never been proven by the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee.

In early December, Pauling wrote to the newspaper demanding a retraction of the letters that it had published. The Herald responded quickly, printing a note explaining that they were “unable to substantiate the claims” of one letter published on December 2nd by Martin Gegnor. That stated, the editors ended their note by declaring that “it is the policy of this newspaper to give free expression to our readers.” They likewise noted that the Herald, in its December 2nd issue, had also printed a long letter from the wife of the president of Western Washington College extolling Pauling’s scientific achievements.

Pauling was not satisfied with the Herald’s response and wrote a second letter to the paper that was published on December 20th. This letter went to great pains to point out how each defamatory statement issued about him was untrue. Although the Herald published Pauling’s letter, they did so while emphasizing that it was his viewpoint and that the paper did not explicitly apologize for its previous actions. This upset Pauling, who suspected that Martin Gegnor was not actually an ordinary resident of Bellingham, Washington but was instead a pen name for another author, possibly a journalist at the newspaper. (A suspicion that was, many years later, proven correct.)

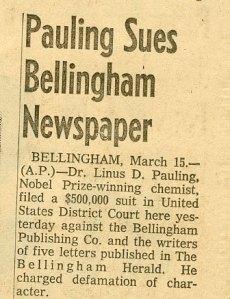

Pauling decided to sue the Bellingham Publishing Company and the letter writers for libel. He later dropped his case against the individuals and decided to focus entirely on the newspaper, which he sued for $500,000. Pauling complained that the allegations in the letters were untrue and that he had no communist tendencies. He also claimed that damages to his reputation might result in the loss of royalties from his three textbooks, which amounted at the time to about $40,000 per year.

In December 1961, the judge overseeing the suit ordered Pauling to release the names of the people who had helped to circulate his nuclear bomb test petition. This very information had been requested of Pauling by the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee in the summer of 1960. Rising contempt of Congress, Pauling had refused to turn it over, fearing that the reputations of his associates would be smeared once their names came to light. This time around, Pauling looked to his Seattle-based lawyer, Francis Hoague, for advice. Hoague replied

It seems to me that you face a dilemma. On one hand, if you dismiss your action against the Bellingham Publishing Company the same ploy will be used in all three remaining libel actions [since instigated by Pauling]. Furthermore, this successful defense to this libel action might lay you open to a rash of defamation, since the defamers would know that they had a defense to any suit brought by you. Also, your dropping of this action, and I assume of the other three actions, would be used by certain columnists to indicate your admission of the truth of the accusations.

Pauling decided to disclose the names of his fellow petitioners, in spite of his desire to protect them from potential federal investigation. The list totaled about 650 names, including approximately 450 Americans.

Page 1 of Pauling’s list of those who helped to circulate the bomb test petition.

In January 1962, before the case came to trial, Pauling offered the Bellingham Publishing Company a settlement: $75,000 in damages plus a retraction. After negotiating for four months, the parties agreed to a penalty of $16,000 plus a retraction. The settlement was likely close to what Pauling would have received through the full prosecution of a successful suit. The outcome also allowed him to spend less in legal fees, and was hoped to deter other news sources from libelous actions of a similar nature.

The Bellingham Herald published its retraction in May 1962, writing

In late November and early December, 1960…this paper published in its Letters to the Editor column five letters in which the writers attacked Dr. Pauling. These letters contained untrue statements which, if believed, would have reflected on Dr. Pauling’s integrity and loyalty to the United States of America. These defamatory letters were published in error in reliance upon the writers, without investigation by the paper. The Herald takes this opportunity to state publicly that it regrets that it published these statements reflecting on the integrity and loyalty of Dr. Pauling.

Three years later, in April 1965, Francis Hoague, Pauling’s Bellingham case lawyer, wrote a letter to him noting the impact that the suit had made in the community. In his observation

Up until the time when you sued the Bellingham Herald, the John Birch Society had a firm grip on city and school affairs in Bellingham and virtually no one dared to challenge them…Your suit was the turning point in this matter, and since then the John Birch Society has had relatively little influence and can be quickly and effectively challenged when necessary. Even the Bellingham Herald has shown a change of heart in liberal matters…so your efforts in that respect were not in vain.

Thirteen years after that, Pauling engaged in a conversation that makes for a compelling coda to the Bellingham story. In a note to self dated February 27, 1978, he wrote

Mrs. Helen Mazur talked to me today. Her husband is Professor of Demography in Western Washington University, Bellingham….

She and her husband arrived at Bellingham just at the time that I came to give the Commencement lecture. We learned when we arrived there that some derogatory material had appeared in the Bellingham Herald. I sued, and the case was settled out of court with payment of $15,000 [sic] to me.

Mrs. Mazur said that when she arrived in Bellingham just at that time she met the president of the local bank. For some reason that she does not understand he began talking to her about me, and said that he had gone to the editor of the newspaper to suggest that something be done. She says that he said that he and the editor had written a letter attacking me, which was then published in the Bellingham Herald. It was this letter, with a false name and address, that was the basis of my suit. She also said that the newspaper borrowed the $15,000 from the banker’s bank in order to make the payment to me. I had not known that the newspaper editor and the banker had conspired to write this letter.