In fashion, tailors and designers get all the credit, but there's an entire world of weavers, dyers, and finishers that are making the things we feel directly against our skin. Just as good food relies on good ingredients, the cutting and sewing of a garment wouldn't mean much without quality materials.

In the last couple of years, I become really interested textiles - not just in terms of how they're used in clothing, but also the broader world of woven goods. Selvedge, for example, is a great publication if you're interested in this kind of stuff. They're aimed at the lay enthusiast, but the articles are enriching, full of information that makes you appreciate the craft that goes into producing quality cloth (even if little of it has to do with menswear).

Most things today are made with synthetic dyes, which were first discovered by accident in 1856. A young English chemist named William Henry Perkin was working in a crude home lab one year, trying to synthesize quinine to help fight malaria. What he ended up making was the world's first aniline dye (the color was mauve), which soon after launched an entirely new industry. Synthetic dyes proved to be cheaper to make and easier to replicate. Within a few decades of their introduction, natural dyes all but disappeared from the Western world.

In the last ten years, however, there's been a renewed interest in natural dyes, blowing around the world of menswear like pollen. The techniques for natural dyeing aren't too different from those people have used for hundreds of years. Up until the mid-19th century, people relied on things such as plants and insects to color their clothes. And in small, often distant communities, those techniques have been the bread-and-butter of micro-economies. Erica Goode recently wrote a great New York Times article about how Mexican artisans are creating extraordinary fabrics in the most traditional of ways.

As a child, Porfirio Gutiérrez hiked into the mountains above the village with his family each fall, collecting the plants they would use to make colorful dyes for blankets and other woven goods. They gathered pericón, a type of marigold that turned the woolen skeins a buttercream color; jarilla leaves that yielded a fresh green; and tree lichen known as old man's beard that dyed wool a yellow as pale as straw.

[...]

Teotitlán del Valle has long been a center for weaving - according to one estimate, there are 2,000 or more looms in the village. In his book, "Oaxaca Journal," Dr. Oliver Sacks, the writer, neurologist and amateur botanist, described the village as having almost a hereditary artisan class. "Virtually everyone in Teotitlán del Valle has a deep and detailed knowledge of weaving and dyeing, and all that goes with it - carding, combing the wool, spinning the yarn, raising the insects on their favorite cactuses, picking the right indigo plants," Dr. Sacks wrote.

Traditionalists like to say that natural dyes are safer, but that's not totally true. Some of the plants used are poisonous and heavy metal salts, such as chrome and tin, are often necessary to affix dyes to yarns. The treatments are known as mordants (from the French verb, "to bite") and they essentially ensure the fabrics don't fade in the wash or sun. In Oaxaca, workers use potassium alum, or potash, for their mordant. The process is more environmentally friendly than modern, industrial techniques, but naturally-dyed fabrics always fade more easily than their synthetic counterparts, which arguably makes them less sustainable anyway. When I talked to Robert Keyte a few years ago, the owner of the last madder silk printer in Macclesfield, he said clients use to complain when ancient madder was made using natural roots. Back then, the dyes would vary every 12.5 yards of silk, which meant sometimes there would be slight color variation across a single tie. Customers demanded consistency.

For the aficionado, however, it's that variation that makes natural dyes so charming. And if you look hard enough, you can still find some great menswear being naturally processed. Brands such as Visvim, Kapital, Tender, and Older Brother incorporate natural dyes into their collections, typically in workwear designs that are meant to quickly show their age over a short period of time.

For example, Kapital famously uses a Japanese technique known as kakishibu, where unripe persimmons are crushed, mixed with water, and left to ferment for about a week. The juice is then extracted and put into storage for about a year, at which point it turns from a bright green to a dark, almost reddish brown. Kapital then uses the dye to color everything from jeans to jackets to shoes. One of my favorite pairs of boots, the side-zips you see here, has been over-dyed in persimmon juice. I find it gives the shoes an interesting effect, where the top layer quickly fades away and reveals a different shade of brown underneath. You can find some wonderful photographs of kakishibu at Kishiko Tajima's Instagram account.

This season's Older Brother collection has also been naturally dyed in coffee. The clothes include everything from button-downs to tees, corduroys to chore coats, tailored jackets to turtlenecks. Colors range from espresso brown to milky mocha. I'm not sure how they achieved the darker colors, as coffee-dyed garments are typically quite light, but I'm not complaining. Who doesn't love the idea of velvety, coffee-dyed corduroy trousers?

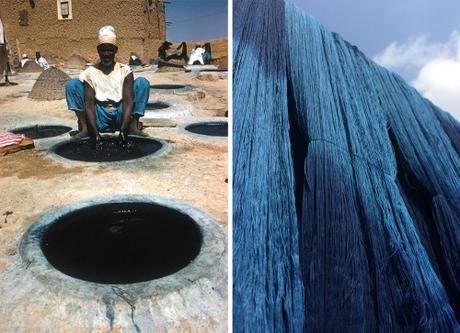

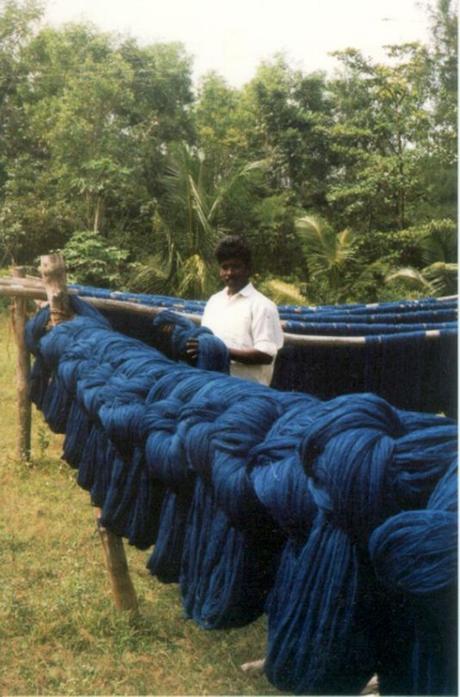

Finally, of course, there's natural indigo, which is brighter and more vibrant than its synthetic counterpart (although I love synthetic indigo as well). Different regions have different methods for making natural indigo, although they all rely on drawing out chemicals from the plant indigofera, from which the color gets its name. Somehow, through that process, the green plant produces a dye that colors things a unique blue. I particularly like Blue Blue Japan's sashiko work coats, Drake's hand-dyed scarves, and Dr. Collector's vintage-cut tees ( their lookbooks are pretty great). Shoes by Pottery has some indigo-dyed sneakers this season; Bleu de Cocagne is a French workwear brand I recently learned about, which sells loose tops, oversized stoles, and traditional Japanese-inspired outerwear.

Little of the above will be useful to readers who only wear tailored clothing. Fast fading colors aren't terribly ideal for suits and sport coats. However, if you have an interest in casualwear, experimentation here can be fun. Synthetic dyes still make up the bulk of my wardrobe, but a bit natural color can give an ensemble some character.

Pictured below are examples of natural indigo and kakishibu fabrics. There are also some great shots of Olivier Grasset from Dr. Collectors, dyeing things from the back of his Southern Californian home. Those images, shot by photographer Ryan Lopez, are outtakes from Amy Leverton's book Denim Dudes, which is pretty great. There are also a billion Youtube videos on how to experiment with natural dyes at home, often using things you can readily find in your kitchen or garden.