It’s hard to separate prep from the clothes that once defined American style – sack suits and button-down collars, at one point, were simply what everyone wore – but to the degree they can be separated, there was a time when prep and trad stood for the values of a certain social class, namely the WASP establishment. Today, prep is a fashion costume like any other, much like European workwear or Japanese futurism. And some of the people that best represent that look have twisted the style to suit their personality. Think of mid-century jazz musicians, Jason Jules, or Ralph Lauren. None of these people represent the proprieties of “traditional” WASP-dom.

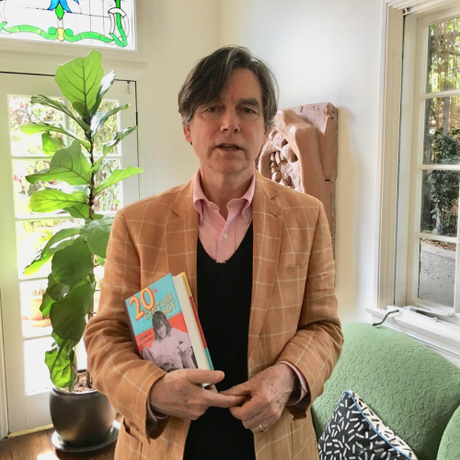

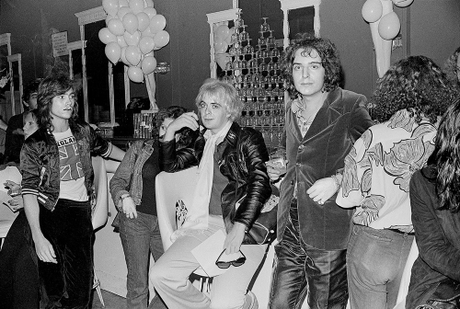

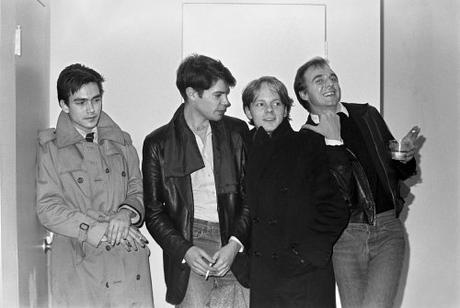

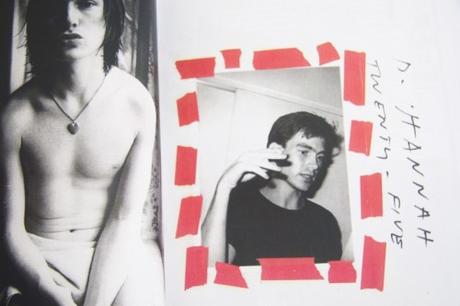

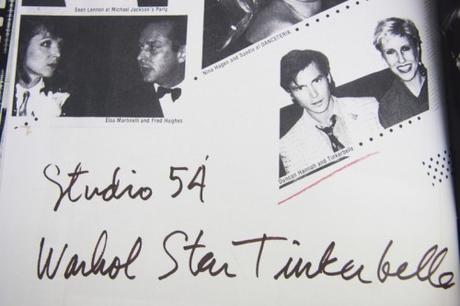

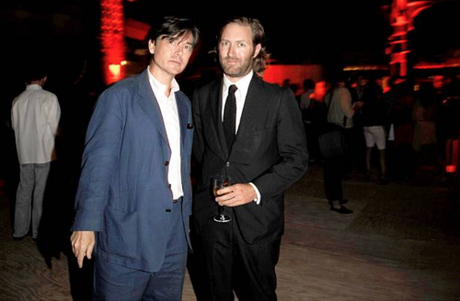

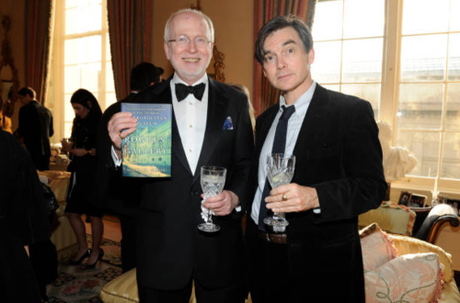

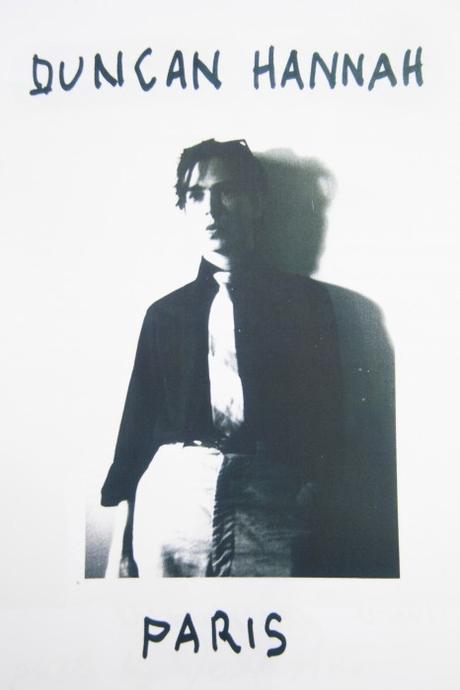

Duncan Hannah is another such figure. His recently released a memoir, Twentieth-Century Boy, is about his time growing in New York City in the 1970s, where he arrived as a 19 year-old art student from Minneapolis. The book is full of charming anecdotes about his encounters with cultural icons from that kinetic decade. Hannah talks about his time partying with Andy Warhol, Bryan Ferry, and David Bowie. Patti Smith once dedicated a poem to him; Amanda Lear invited him to have drinks with her and Salvador Dalí at the St. Regis hotel. Supposedly, Dalí made a grand entrance, arriving in a golden cape and gloriously announcing in the third person, “Dalí … is here!”

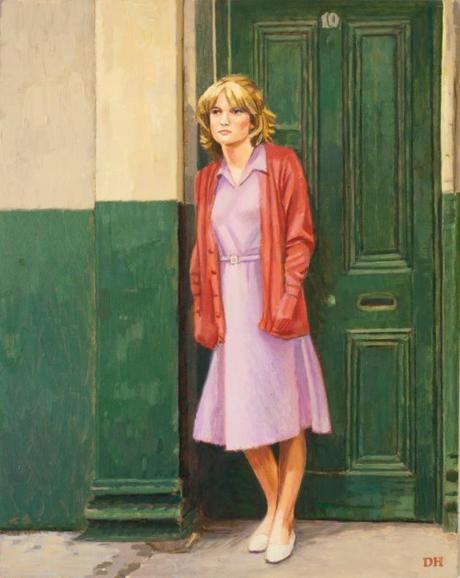

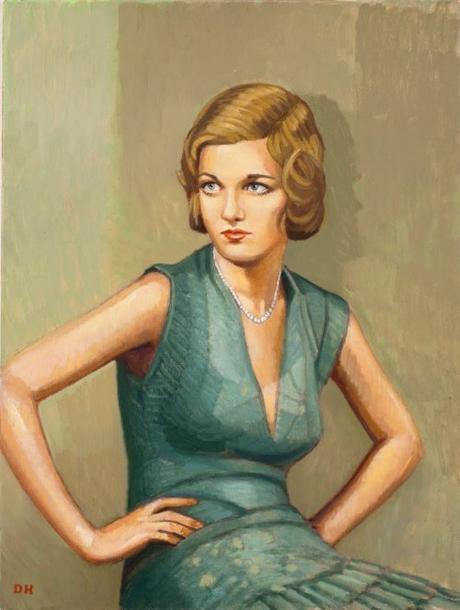

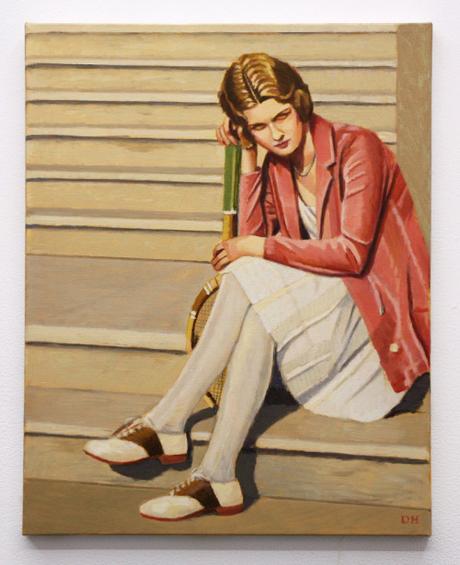

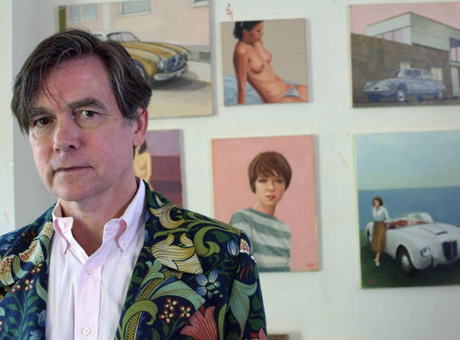

Hannah’s real claim to fame, however, is as a painter. His work hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and has graced dozens of book covers. He paints in the realist and figurative traditions of his heroes, such as Edward Hopper and Fairfield Porter, and his subjects are often of mid-century American scenes, where there’s a beautiful sense of stillness. This is unusual because, as anyone who has taken an art theory class knows, art today is often more concerned with ideas than craft. Contemporary art is typically focused on meaning and message; less on beauty for its own sake. Throughout his career, Hannah has encountered some pushback from people who couldn’t tell if he’s trying to make a statement with such passé paintings. His contemporaries once thought he was being ironic and critiquing art history when, as Hannah puts it, this was more of a “love letter to art history.”

“I’ve basically ignored the avant-garde,” Hannah once said in an interview at The Paris Review. “I was surprised by the conformity of the art world. Because I always thought from afar that it was a bunch of eccentrics who couldn’t really agree on anything and were marching to their own drummers. But there was a rigidity to it that really kind of baffled me.” In story at The New York Times, he recalls what happened when no-wave musician Art Lindsay attended one of his exhibitions.

We were old friends from years spent in the nightclubs, but he’d never really had a chance to see my work aside from an album cover illustration. Arto turned to me and said” — here Mr. Hannah mimicked Mr. Lindsay’s raised eyebrow and suspicious tone — “‘Is this what you do? These are like real paintings.’ His message was clear: ‘I thought you were cool!’ Well, I love painting. To me, Whistler is cool. Vuillard is really cool. I don’t think, ‘Oh that’s fusty and dead.’ When somebody’s good, nobody betters them. I’ve never seen art history as ‘this’ replacing ‘that.’

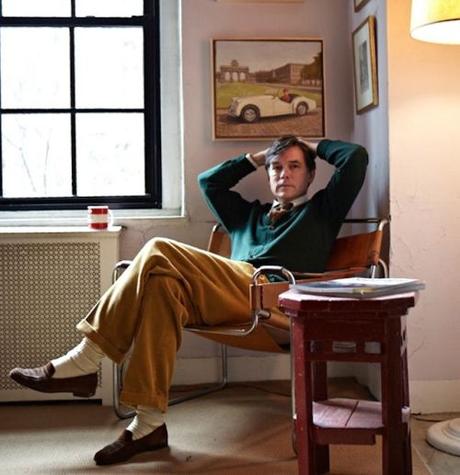

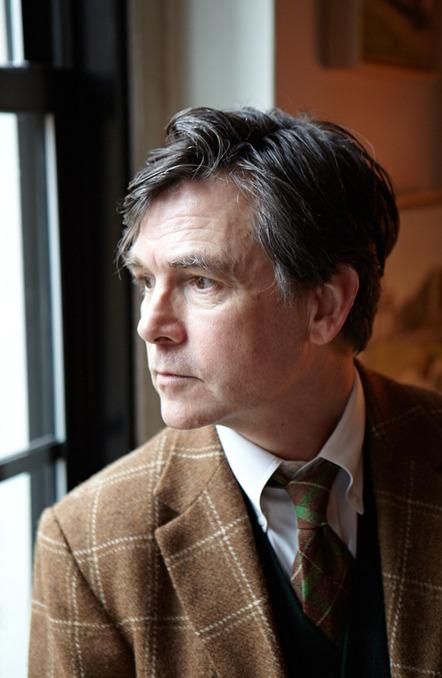

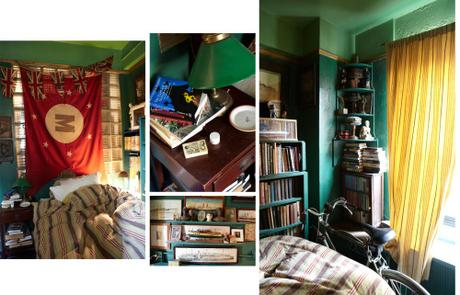

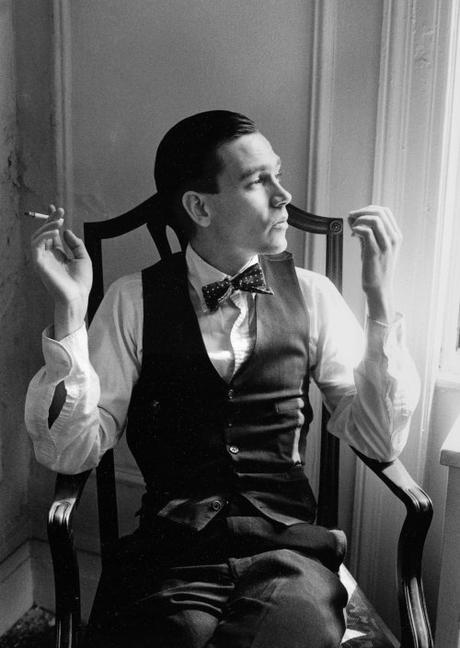

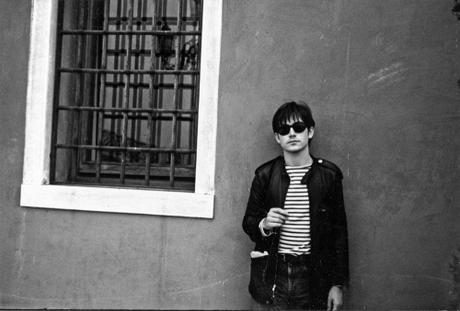

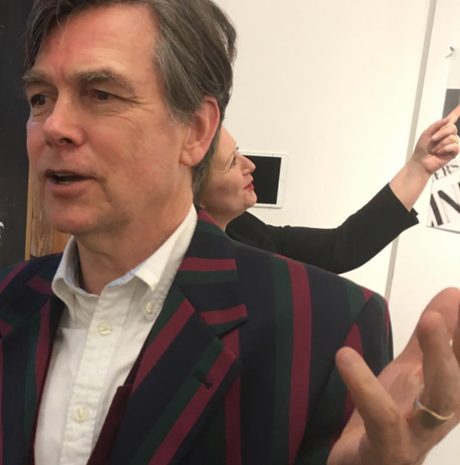

That same earnestness is reflected in Hannah’s personal style, which can be roughly described as mid-century prep, if not at least traditionally American. He wears purple suede sport coats and three-button Shetland tweeds with campy suspenders; Fair Isle vests and unlined button-down collars; Norwegian welted brogues and brick-soled white bucks. His outfits are often a hodgepodge of things, combining items that should never go together, at least canonically – fuschia shirts with pinstriped suits, lime-green silk ties with tweed jackets. Hannah says he tries to dress like painters did back when “they used to dress moderately well.” And he does it without an ounce of irony.

There’s a sense of FU to Hannah’s style that could be chalked up to prep. His father, after all, graduated from Harvard and was besotted with Brooks Brothers and J. Press. “He was part of the country club set,” Hannah says in David Coggins’ book, Men and Style. Apparently that meant wearing Lilly Pulitzer pants, velvet smoking jackets, and big blazer crests – “even on bathrobes.” His father was fastidious about his dress and had certain rules, such as always matching the color of his leather belt to his dress shoes.

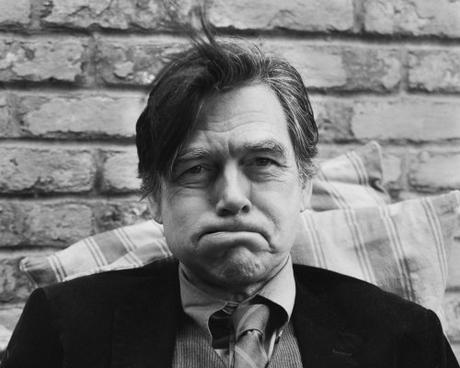

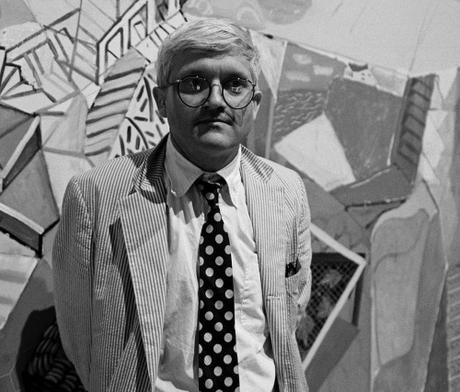

However, I mostly think of Hannah’s style as a sort of art school prep – a dishabille look similar to David Hockney’s, who was known for his purposeful ignorance of “the rules.” Hockney wore athletic sweatshirts and sneakers with tailored clothing decades before the combo became a menswear cliché. He fearlessly used brightly colored socks, bold eyewear, and floppy knit ties to great effect, ignoring the general advice of surrounding one loud item with quieter pieces. A Savile Row tailor once asked Hockney how he achieved his wonderfully rumpled look. Hockney answered: “I don’t own any hangers.”

Hannah’s style is similarly eccentric in that bohemian way, layering one bold item on top of another. In Men and Style, Hannah recalls how he dressed in his youth, which I think says more about his style than anything:

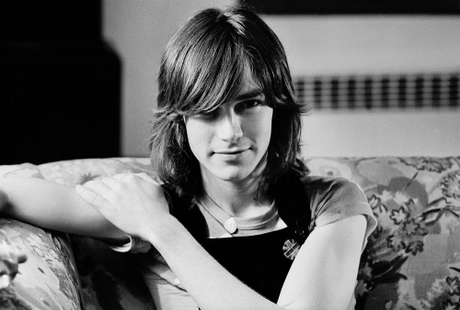

In college, I was all over the place. I went to Bard and Ziggy Stardust had just come out, so I was dressing in a Bowie-esque kind of fashion, which is ridiculous in a rural setting. Huge black fedoras and a lot of, well, women’s clothes. There was a thrift shop in Woodstock that sold great Joan Crawford overcoats, which I thought looked very forties space age. I would see one and say ‘Oh that’s perfect!’ Whenever I flew back to Minneapolis in those clothes, I was always pulled over by security and frisked. When my poor father picked me up at the other end, he said ‘Oh God, what is this, Mildred Pierce?

When he wore tailored clothing, it was more punk than prep. In Twentieth-Century Boy, Hannah remembers a party he once attended: “I sat with singer Robert Palmer […] he wanted to know where I got my corduroy suit. I told him it was an old Brooks Brothers number that I dyed with plum-colored Rit in the bathtub. He seemed disappointed that he couldn’t go out and get this stuff. But it’s all do-it-yourself around here.” Hannah’s style has mellowed out as he’s gotten older, but he still wears things his own way. “I’m less attracted to the flashy, or the zeitgeist. I’m interested in what’s timeless, for instance. I don’t really care about what’s new, I care about what’s good.”

Eccentricity in dress, I think, only works when it comes from a real place. When you’re more interesting than your clothes, rather than the other way around. It’s often best on artists, musicians, and other creative types. Hannah came up during an age of creative autodidacts and ‘70s romanticism. These clothes would be ridiculous on anyone else, but they look right on him. They remind me of something Jason Jules said when I talked to him last month: “Many guys have taken what are essentially classic American clothes and turned them into something that reflects their own lifestyle. That’s the goal.”

(h/t to Richard for the lead on this post)