Imagine my somewhat qualified delight, gentle readers, when I realised my first Saturday blog of the new year was going to be all about tapestry ! Fortunately, I have an angle on it in the person of my favorite artisan (writer, designer and social activist) from the late 19th century Arts and Crafts movement, William Morris (1834-1896).Influenced by the writings of John Ruskin and through close association with the artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Morris championed the craftsmanship of the artisan in the face of the modern factory system (which he regarded as a form of slavery). With a group of friends and fellow artists he founded Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co in 1861, designing and making furniture, textiles and wallpapers by hand, in the spirit of the best medieval Gothic tradition, as opposed to using a factory's automated production methods. It was only a matter of time before he wanted to incorporate tapestry into the company's offerings.Perceiving there was no contemporary who could instruct him how to do it in the way he envisaged, Morris basically taught himself the art of weaving on a loom he set up in his bedroom and using an old French technical manual as his guide. He designed and wove his first tapestry, Acanthus and Vine (illustrated below) on that bedroom loom in 1879. I think you'll agree it's pretty cool.

Acanthus and Vine (William Morris, 1879)

When Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co relocated to larger premises at Merton Abbey in south London in 1881, there was space enough to rig up four tapestry looms and to train apprentice weavers. Many other beautiful designs followed, in the spirit of the best historic medieval precedents of 14th and 15th century tapestry-making. Morris's tapestries met with considerable commercial and critical success and were bought by patrons not only among England's nouveau riche but also the rising entrepreneurial classes in North America, South Africa and Australia for the walls of their new palaces, an irony that would not have been lost on Morris himself. He could at least content himself with the knowledge that to an extent they had bought into his radical anti-mechanised ethic.I thought I'd include two poems this week. The first has to be one of William Morris's own, written in praise of his bed (again illustrated below). Morris took joint tenancy (with Dante Gabriel Rossetti) of Kelmscott Manor, a large Elizabethan house in Oxfordshire, in 1871 and spent much of his time there in his later years. The bed, partly Elizabethan, partly Jacobean, was decorated with embroidered pelmet, curtains and bedspread made by his wife Jane and daughter May, with assistance from W.B. Yeats' sister Lily.

William Morris's bed at Kelmscott

The poem has an almost fin-de-siecle aesthetic to it, possibly not surprising given that it was composed in the last decade of the 19th century and within five years of the end of Morris's life (though for all his protestation that he was old he was still in his fifties when he wrote it). I think it fits the mood of this cold, dark, windy January.For The Bed At KelmscottThe wind's on the woldAnd night is a-cold,And Thames runs chill'Twixt mead and hill.But kind and dearIs the old house hereAnd my heart is warm'Midst winter's harm.Rest then and rest,And think of the best'Twixt summer and spring,When all birds singIn the town of the tree,And ye in meAnd scarce dare move,Lest earth and its loveShould fade awayEre the full of the day.I am old and have seenMany things that have been;Both grief and peaceAnd wane and increaseNo tale I tellOf ill or well,But this I say:Night treadeth on day,And for worst or bestRight good is rest.

William Morris, 1891

I'm not going to leave it there. Let's turn to warmer climes and farther times and the story of Penelope (as mentioned at the beginning). For those of you not familiar with the Odyssey, Penelope was the wife of Odysseus, King of Ithaca. Prior to marrying Penelope, Odysseus had been one of the suitors of Helen, "the most beautiful woman in the world". She finally chose Menelaus as her husband and, at Odysseus's suggestion, all the unsuccessful suitors took an oath (known as the Oath of Tyndareus) that they would come to the aid of Menelaus if ever anyone tried to steal Helen from him.

When (inevitably) Helen was abducted/seduced by Prince Paris and taken to Troy, Menelaus invoked the Oath and so began the Trojan War. Initially Odysseus was away from Ithaca for ten years, fighting until Troy was defeated and Menelaus was able to reclaim Helen (as told in the Iliad). It then took Odysseus another ten years through various trials and tribulations (as recounted in the Odyssey) to make his way back home to Ithaca to be reunited with his Queen, probably the second most beautiful woman in the world (if Carlsberg wrote epic poems).

Penelope was possibly only in her early twenties when Odysseus went off to war. He left her with a young son to bring up and a kingdom to manage - effectively a queendom for two decades. Of course she had suitors (none of whom expected that Odysseus would return), one hundred and eight of them apparently - that's two full packs of cards including jokers! But Penelope kept believing. She was also an expert weaver and used a clever ploy to hold her many admirers at a suitable distance by promising she would make her choice once she completed the tapestry she was working on. Every day she would spend time weaving away industriously at her loom in the royal palace, every evening she would entertain those seeking her hand, and every night she would secretly unpick part of what she had woven during the day, so the tapestry never neared completion.

Eventually Odysseus arrived back in Ithaca, dispatched the suitors and reclaimed his kingdom and his wife - but was it as simple as all that? Twenty years is a long time. Sarah Gillespie (musician and poet) wrote a collection evocatively titled Queen Ithaca Blues and I don't know if that's a familial reference to Ithaca NY or to the Greek fable, but it got me pondering how Penelope might have felt when her absent husband finally re-entered her life.

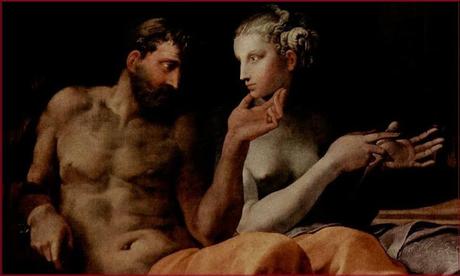

Odysseus and Penelope (Francesco Primaticcio, 1563)

I've gone for an ekphrastic approach (a poem inspired by a painting) for this latest composition. I've studied Primaticcio's rendition for some while and used it to prompt an internal monologue, taking a bit of a flier in imagining what Queen Ithaca might be thinking in the immediate aftermath of their reunion.Fates LoomYou hold my gaze between finger and thumbasking how was it for me and I wonderdo you mean the last twenty minutesor the last twenty years. But no words come.I'm dumbstruck to realize in the half-darkof our private room in our freshly unmade marriage bed that the fond decades dreamI'd been weaving of having you back againmight need some unpicking and instinctivelymy hands work as they have in shadowsacross so many nights only this time the threadis invisible the unravelling all in my head.

I've been faithful to you in body and soulwhich is likely more than you could swearbut I have also ruled in lieu for so longthat I don't believe we can be as we were.I would not have acted other than I did thoughif you think you come back to an easy lifewith a pliant decorous wife at your command......except I can't express such thoughts right nowwhen all you want to hear is how I missed youso I just say welcome home wandering manresolving in the moment that at a later date I must prove mistress of the loom of fate.

Thanks for reading, S ;-) Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to Facebook