If there’s any country that knows how to make cold-weather clothes, it’s Scotland. Heavy tweeds, cabled sweaters, and what I think is the best cashmere in the world. Recently, David Marx – the author behind Ametora – wrote a great essay on how Japan has become an important export market for traditional Scottish clothes and textiles. The article was first published in Vanguards Magazine, a bi-annual publication celebrating design and products.

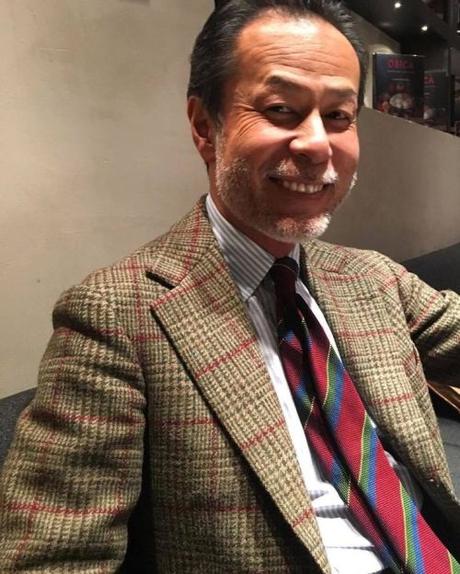

Marx’s essay starts with how traditional Scottish goods landed in Japan in the first place. Mid-century American clothes, marketed as Ivy Style, originally brought things such as Harris Tweed to the island. Pictured above, for example, is Tailor Caid’s Yuhei Yamamoto (photo by Mark Cho), wearing a classic, soft-shouldered, American-style overcoat. It’s this sort of tweedy look that would later open up the Japanese market to other Scottish specialities, such as fisherman knits and teaseled scarves. Marx’s essay is republished in full here with permission, but if you like it, check out Vanguards’ second issue, from which this is taken (there’s a graphic novel in there about Aero Leathers). Vanguards is also selling a specially designed bandana that accompanies this story.

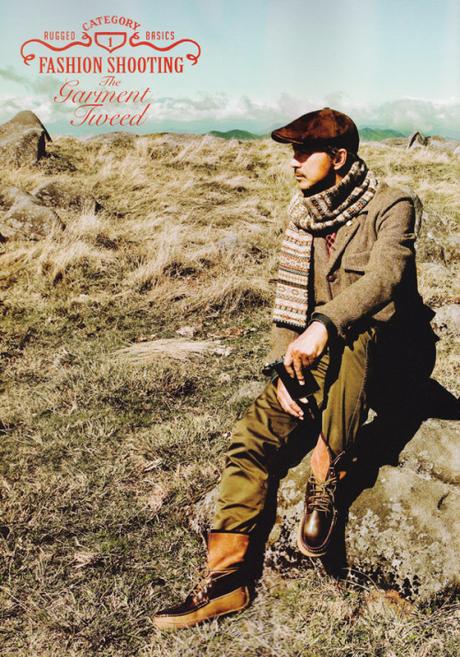

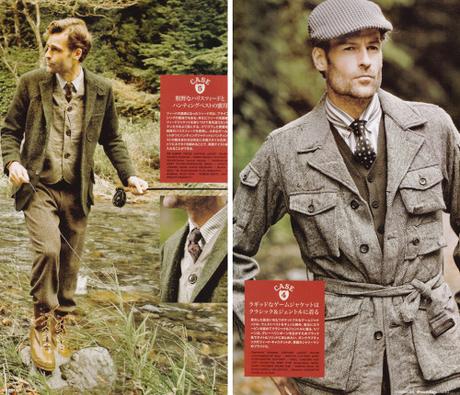

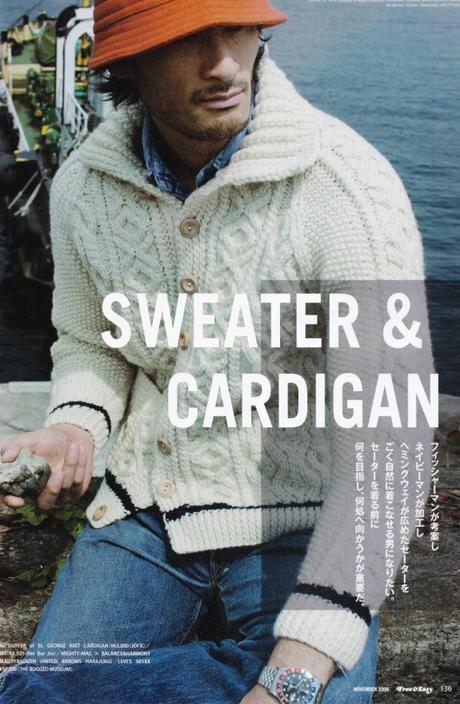

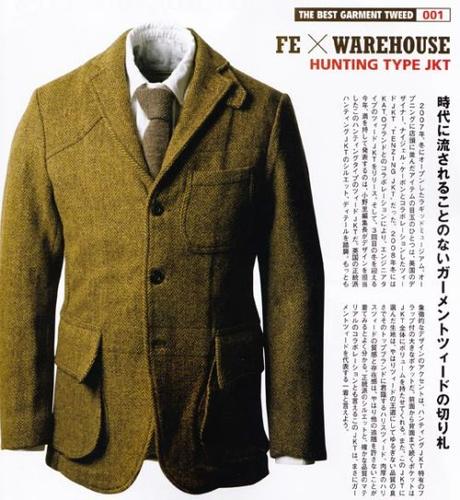

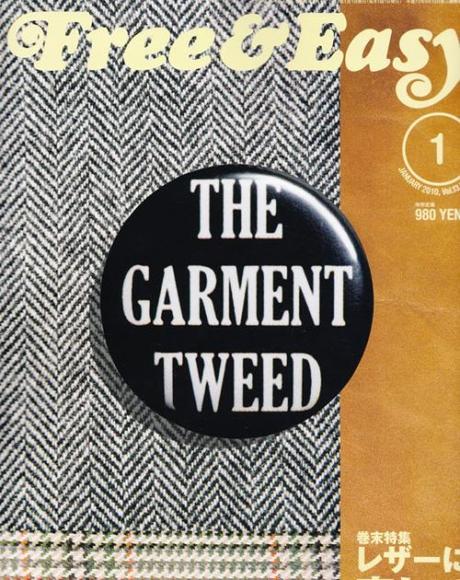

Each autumn in Tokyo, there are a series of annual rituals which alert shoppers that crisp weather and burgundy maple leaves are just around the corner. First, traditional menswear retailer Beams Plus covers an entire wall with stacks of fluffy Jamieson-made sweaters in a crayon’s box worth of color variations. Next, stores such as United Arrows, Tomorrowland, and Ships join Beams in bringing out piles of thick wool shawl cardigans from Inverallan, each with a tag certifying the sweater’s hand-knit origin. In November, men celebrate the bountiful harvest of late summer trunk shows: their made-to-measure Harris Tweed sports coats have arrived. They match their herringbone and dogtooth jackets with explosions of fair isle patterns and tartan scarves to scatter festive color across the Tokyo streets.

After living in Japan for more than a decade, I have taken these rituals for granted, believing that Scottish goods are a common part of the consumer landscape in every major metropolitan area. And yet on a recent trip to New York City – once a bastion of men’s traditional wear – I could find hardly any retailer with a fraction of the variety of Shetland sweaters that one stumbles upon in Tokyo. Why would Scottish knitwear, some of the best in the world, not be stocked in all the major fashion capitals? Viewed in a global context, suddenly it became very clear: Traditional Scottish staples have become a significant and standard part of the Japanese wardrobe. As Scottish-born, Kobe-based illustrator Graeme McNee says, “When I think of classic Scottish brands I realize I’m just as likely, perhaps even more likely, to see them in Japanese stores as I am back home.”

This starts with the aforementioned men’s knits but extends to women’s high-end scarves, such as Scottish cashmere brand, Begg & Co. And then there is tartan. The Scottish check pattern is now ubiquitous in Japan, perhaps a more common part of the daily scenery than silk kimonos. Many school girl uniforms’ pleated skirts come in a muted tartan pattern pleated skirt. And famously, the trademark shopping bags of prestigious department store Isetan come in tartan, MacMillan Ancient Clan for the women’s department, Black Watch for the men’s. Not to be outdone, three-centuries old department store Mitsukoshi has its own original centennial tartan, registered and permanently preserved in the National Records of Scotland.

This leads us to the question: How exactly did Japan become so enchanted with Scottish wools and patterns?

The story, intriguingly, is not a tale that flows directly from Edinburgh to Tokyo - but goes through the Ivy League colleges of the United States. Mark Hogarth, Creative Director of Harris Tweed, notes, “There wasn’t some grand plan to export Harris Tweed to Japan. It came by the preppy American look.”

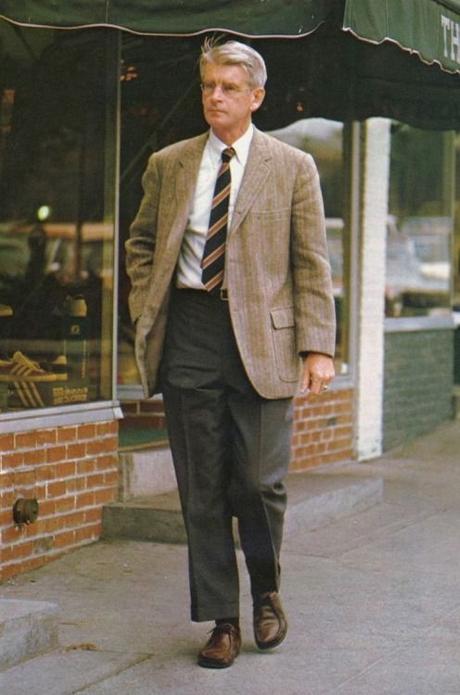

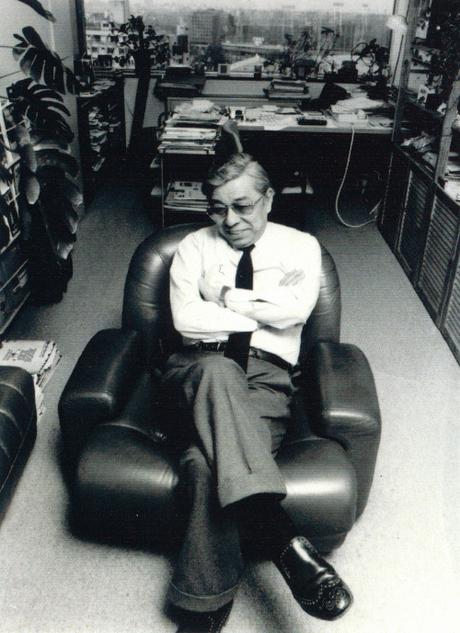

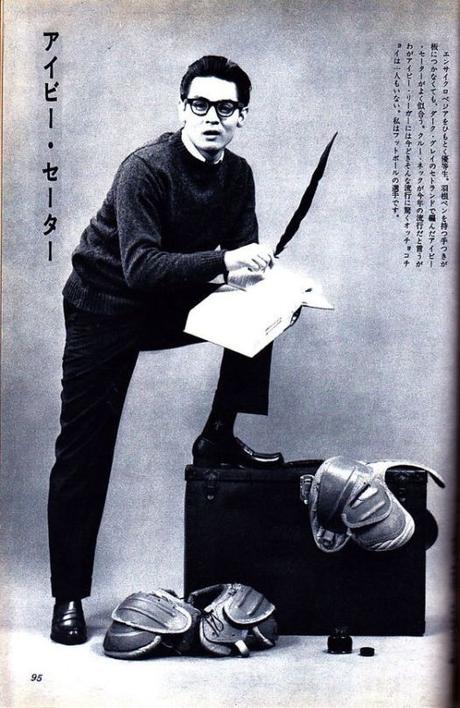

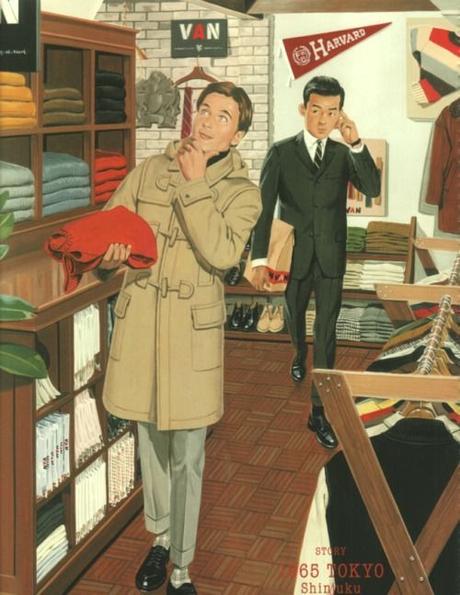

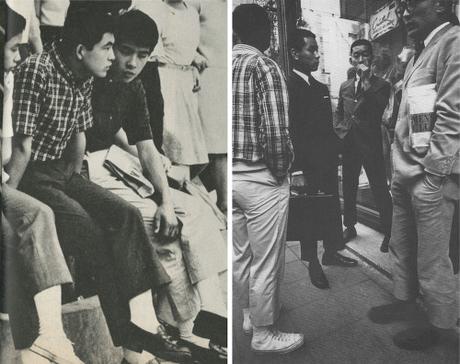

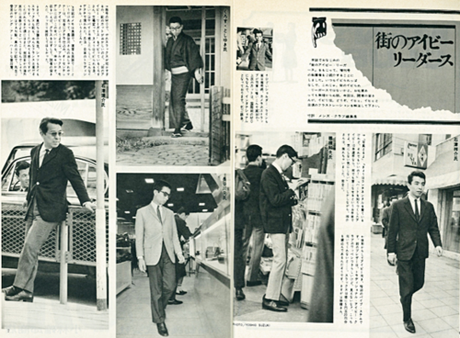

Specifically, back in 1959, fashion entrepreneur Kensuke Ishizu of the brand VAN Jacket was looking for a new style of ready-to-wear clothing to sell to young men. Upon visiting Princeton University, Ishizu discovered stylish students in tweed blazers, repp ties, button-down shirts, gray flannel pants, and penny loafers. This was the “Ivy” style he had read about in American magazines. Upon returning to Japan, he turned his company into an Ivy fashion factory – making local copies of American garments and using his close connections to the fledgling men’s fashion magazine Men’s Club to proselytize Japanese youth on dressing like American college students.

As Ishizu’s brand VAN Jacket attempted to become more and more authentic to the source material, Japanese Ivy style advocated its adherents to wear the same Scottish tweeds and tartans sold at American campus stores such as J. Press. Over the next few decades, as Ivy became the “basics” of Japanese menswear, Scottish styles were at the center of the trend. And when youth tired of American clothing and fell instead for “British traditional” in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Scottish fabrics again managed to assert themselves as part of the uniform. (And, of course, it didn’t hurt when the tartan-clad Bay City Rollers became a Japanese pop culture sensation in 1976.)

With the “Preppy” boom and resurgence of American collegiate wear in 1979, Scotland firmly established itself as ground zero for the “trad” clothing style. In 1981, writer Hisayuki Nakamuta released a now classic book called, Traditional Fashion: From Tartan Check to Button Downs – known to be one of Uniqlo founder Tadashi Yanai’s favorite style references. Nakamuta’s world journey of trad bastions starts not in London or Boston – but Edinburgh. He traveled around Scotland to tour the famous brands at the time: clothmakers Harrison’s of Edinburgh, McBean & Bishop Ltd., and Lord Cawdor, as well as scarf brand Glentana and shirtmakers Robert White & Co. Upon returning from his sojourn, Nakamuta reiterated that being “trad” necessitated a focus on Scotland: “In the last ten years or so, British-styled interior design has been all the rage at Japanese men’s shops, but you have to admit that this is just a copy of provincial New England stores. If they are looking to add a more authentic nuance, whether through the goods stocked or the interior design, they should take major reference from the clothing customs of ancient Scottish castles and golf course club houses.” In other words, to be authentically “American” required being authentically “Scottish.”

In 1983, the Preppy boom evaporated overnight, and yet the rugged simplicity of Scottish brands kept them well suited for the next trend in the late 1980s, American Casual (amekaji). Hundreds of casual “import shops” popped up in Japan to serve casual clothing fans, and these independent stores stocked not just Levi’s leather bomber jackets from the U.S., but also French Breton striped shirts, Irish Aran sweaters, and Scottish knits.

Today, the traditional menswear label Beams Plus is the banner-carrier for Japan’s long-time obsession over Ivy, Preppy, and American Casual. And as a good student of the past, steward of the present, and innovator towards the future, Beams Plus stocks Inverallan cable knits, Jamieson’s Fair Isle and solid Shetlands, Balmoral vests, William Lockie lambswool and merinos, and Highland 2000 beanies. Director Hideki Mizobata explains, “Scottish fabrics for us represent a traditional way of making things that has not changed. We deeply respect those traditional styles, and we sell them not as a trend but as ‘menswear basics.'” Women wanting the same Scottish brands but in smaller sizes need go no further than Beams Boy – one of Beams’ core women’s lines with a similar aesthetic focus on traditional looks.

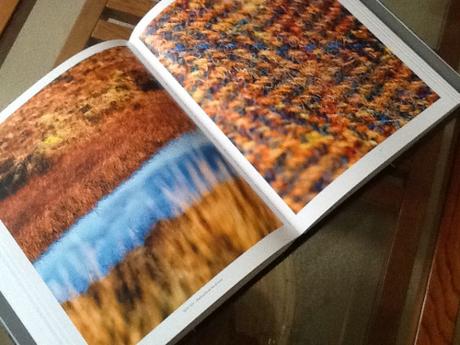

Specialty stores such as Beams and Ships keep Scottish brands in constant circulation, but Japanese magazines help tell the companies’ stories so that the goods resonate with consumers. Yoshimi Hasegawa, author of Harris Tweed and Aran Sweaters, writes, “Japanese magazines have controlled and created the fashion market since 1970’s, and Harris Tweed and Jamieson are commonly very popular themes for these magazines.” Hasegawa’s own book does its part as well, connecting stunning images of the weathered Scottish landscape and gloriously patinated factories to the high-quality apparel those locations produce.

While Japanese companies have surpassed American brands in creating classic items such as jeans, button-down shirts, and athletic sweatshirts, it is notable that Japan still imports high-end Shetlands and cable knits from Scotland rather than attempting its own versions. One reason is that Japan has never excelled at wool production. Compared to silk and cotton, wool was not used in Japanese clothing until the late 19th century when men started to don British suits. Almost all of this wool for these suits was imported, and prestige has remained with overseas fabric makers since that time. Today Japan’s wool spinners and weavers are relatively unknown, especially compared to synthetics powerhouses Teijin, Toray, and Asahi Kasei, or denim producers Kaihara and Kurabo. Japanese companies can’t beat Scotland at producing and knitting high-quality wool – so they have just always imported the best of the best.

This all explains how Japan became the number one export market for Harris Tweed – a long-term relationship that has helped lift the Scottish company to new heights. Creative Director Mark Hogarth says, “When the Harris Tweed brand was at its nadir, from 2003-2007, it was on a life-support machine. The two markets that saved Harris Tweed were Parisian fashion houses and Japanese streetwear companies.”

The Harris-Japan connection today, however, is not purely of buyer and seller, but a more symbiotic set of inter-influences. Hogarth commends the Japanese on their “ability to use quintessential foreign textiles and almost redefine them.” A key piece in the re-emergence of Harris Tweed in the last decade, for example, was a patchwork tweed jacket from fashion director Nick Wooster’s label, made in partnership with Japanese specialty shop United Arrows. Hogarth notes “how important it is going forward that we have a significant market in Japan, because the attention to detail, the quality of the cut, and the overall look in Japan undoubtedly lead other markets to the belief that Harris Tweed is a quality fabric of fashion.”

Harris Tweed is actually so popular in Japan that unscrupulous parties have tried to latch on to its success. Over the last year, bargain retailers have made cheap goods and convenience store trinkets with a combination of Harris Tweed and local low-quality fabrics. The Harris Tweed Authority has engaged on a nationwide crackdown and set forth on a mission to re-educate Japanese consumers about the integrity of the fabric.

This is a key step: Protecting authenticity is critical to Scottish brands’ success in Japan. Ann Ryley, Sales and Marketing Director of Begg & Co. agrees, “The Japanese buyers above all appreciate the quality of the Begg & Co products. They clearly understand our heritage and the high level of craftsmanship involved.” A continued relationship between the two countries hence requires maintaining the image that Scottish-made garments are the living embodiment of a centuries-old tradition. As Yoshimi Hasegawa says, “Japanese men’s fashion consumers are really fascinated by the brands which have authentic historical stories.”

At the moment, there is something nearly religious about the Japanese respect for honmono – “real things” – and Scottish brands and fabrics enjoy a bright halo of quality, style, and tradition. (If this religious language seems overblown, every year, a good number of Japanese tourists head out to the Outer Hebrides to make a “pilgrimage” of the Harris Tweed factory.) The popularity in Japan proves that Scottish brands enjoy the most powerful asset in all of today’s fashion world: a true and clear sense of history. – W. DAVID MARX

(For more of David Marx’s work, you can check out his book Ametora, which explores how Japan saved classic American style. Vanguards Magazine can be found here. Their second issue, from which the article above was taken, can be had for just £8.)