Step aside Cesar Milan—these days when you want to know what the dog really saw, ask a scientist. While studies of domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) have been fundamental to neuroscience—it was Pavlov’s dog after all that drooled when it heard that bell—dog studies are undergoing a renaissance due to advances in genetic and brain-scanning techniques. Dogs are emerging as unique research subjects, due to their evolutionary history, close relationship with humans, high intelligence, and most importantly their ability to sit. (Sit still while their brain is being scanned that is.)

Genetically, dog’s similarity to wolves makes for easy studies comparing the two species behavioral and genetic differences. The way we have inbred dogs into different breeds also allows us to compare traits between species and uncover the genomic differences that have caused them.

Cognitively, dogs display some impressive traits that are rare outside of humans. They can memorize hundreds of human words and can understand the meaning of gestures like pointing (e.g. that the important part of pointing is what your are pointing to, not just the shape of the hand). They also show advanced theory of mind understanding gaze, attention, and practicing deception. Because dogs have these abilities along with the ability to sit still in an fMRI machine and a brain size amenable to scanning, recent studies have investigated at dog’s ability to interpret human communication.

In this blog post I’ll discuss some recent studies: evolutionary studies comparing dogs to wolves, studies probing whether dogs understand what we say and how their brains process speech, and finally studies comparing different breeds of dogs in the search for genetic markers of mental illness.

The Origin of Man’s Best Friend

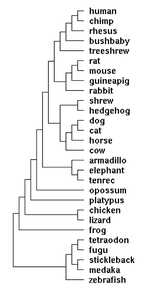

Pop quiz: which animal is more closely related to humans—mice or dogs?

It’s unclear how the human’s relationship with dogs began. For example, did humans actively seek out and domesticate dogs, or did dogs flock to early farms, eating human food scraps, and the ones we liked, we let stick around. At the time of the agricultural revolution 10,000 years ago, humans and dog genomes both evolved, modifying enzymes to allow for better processing of the carbohydrates found in the grains we cultivated.

If you want to hear more, check out this interview with the study’s author.

A study published just last week suggests that this change from hunter to scavenger may have also affected dog’s appetite for risk. Although C.M. Coolidge immortalized dogs as gamblers for a series of cigar advertisements, the domestication of dogs may actually have made them risk-adverse. Given a choice between receiving a reward of guaranteed but inferior food, or a 50-50 chance at getting either a tastier treat or nothing, 80% of wolves chose the risky option, whereas dogs did so only 58% of the time[1]. The authors of this study argue that for species with unstable food sources like hunters greater exploration is necessary, and because exploration is inherently risky these species tend to be greater risk-takers. The dogs and wolves all grew up in the same conditions at the Wolf Science Center in Dorfes, Austria, so differences observed are likely to stem from genes not different developmental experiences.

What do dogs understand?

Dogs were the first species that humans domesticated, and as such have acquired the ability to understand and communicate with humans, but how much do they realize understand and neuroscientifically speaking, how do they do it? fMRI brain scans depend on the research subject staying completely still. We can tell humans to stay still, but most fMRI studies of animals use anesthesia or immobilization.

Watching a program about military dogs trained to jump out of helicopters, scientist Greg Berns had a hunch. If dogs showed that much discipline, they could also be train to stay still and calm through the loud racket generated by an fMRI machine. By scanning the brains of dogs, we could apply the techniques of modern cognitive science to study how dogs had adapted to understand us and become integrated into our families. His hunch was right. He trained his own dog Callie, to sit inside the fMRI machine and made history, generating the first fMRI scan of an unrestrained thinking dog’s brain—showing how the dog’s brain responded when it saw a hand signal that indicated it would get a reward. Berns outlines the story of his pioneering research and findings in his book, How Dogs Love Us.

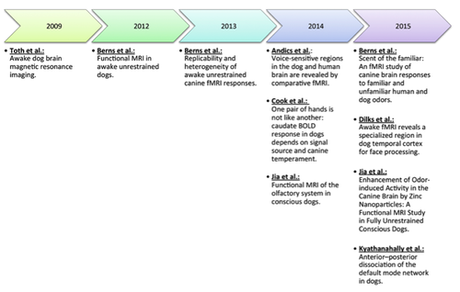

Since then, a variety of groups have begun to study dog brain activity, during a variety of tasks using fMRI:

From Thompkins et al., 2016 Early days of dog MRI studies show upward trend.

Just last week, a new study published in Science, Hungarian researcher Attila Andics and his group showed that with dogs, it’s not just what you say but what you say and how you say it. Inside the scanner, they played the dogs recordings of either praising words, like ‘clever’—actually, they used the Hungarian equivalent ‘ügyes’—or separate words they thought would have no meaning to the dogs like ‘olyan,’ which means ‘such.’ These words were said in neutral tones and in tones consistent with praise. Dogs showed three distinct patterns of neural activity: a set of responses sensitive to the words themselves, another sensitive to the intonation of words, and a final pattern when the praise words were combined with the congratulatory intonation.

Here, researcher Attila Andics explains the research:

Interestingly consistent with what has been observed in humans, the left hemisphere appeared more important for the dogs’ processing of words themselves, possibly due to the left hemisphere’s preferential ability to process rapidly changing acoustic signals, as has been observed in humans and gerbils. Also, like humans, the dogs preferentially processed intonation using their right hemisphere. Perhaps most interestingly, only one sound combination activated the dogs’ reward systems, the combination of both praise words and praise intonation, indicating that the dogs may be combining information from these lexical and tonal processing systems to inform their decisions.

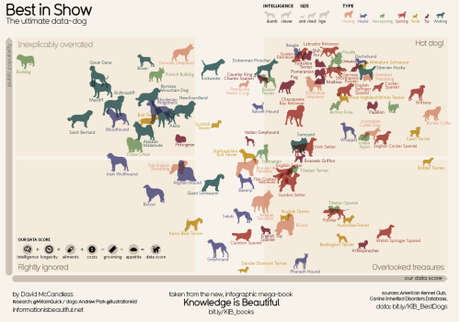

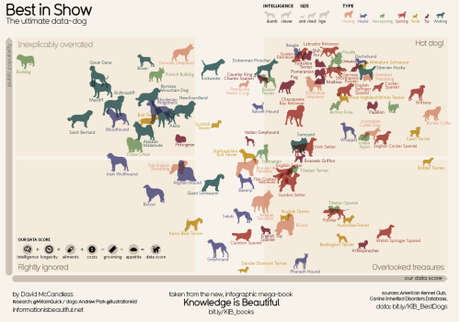

From Information is Beautiful – How does your dog stack up?

From Information is Beautiful – How does your dog stack up?

Dog Breeds and Brain Disease

Selective breeding to generate inbred or ‘purebred’ lines of dogs selected for certain traits, has also lead some breeds to become enriched for genetic disorders. The presence of these afflicted breeds, combined with dog’s high intelligence and complex behavior and now our ability to scan their brains in various behavioral tasks, makes the dog an amazing model organism for discovering and understanding the genetics and mechanisms of brain diseases.

One of modern neuroscience’s greatest success stories has been discovering the cause of narcolepsy. Many Dobermann pinschers suffer from narcolepsy, and Emmanuel Mignot of Stanford University studied these Dobermanns, eventually discovering the gene that made them narcoleptic.

Mignot found a mutation to the dog’s hypocretin receptor 2 (also known as the orexin receptor 2), was found to be the culprit, in 1999. While the exact same mutation does not cause narcolepsy, in humans, this study identified the hypocretin pathway as a key pathway in regulating sleep that was disrupted in narcolepsy. Based on these findings, in 2000, doctors realized that a majority of patients with narcolepsy show undetectable levels of hypocretin in their cerebral spinal fluid, while it was detectable in every control.

Based on these discoveries, drug companies researched orexin blocker suvorexant, and the FDA approved it in 2014 as the first in a new class of sleeping pill to help treat insomnia. Most drugs that target the brain have been discovered serendipitously, and this is one of the few success stories of a basic science finding, informing drug synthesis, clinical trials, and finally resulting in an FDA-approved product. And while research into dog narcolepsy has so far only resulted in a drug for human insomnia that blocks the hypocretin receptor, almost mimicking insomnia, and not a drug for narcolepsy, a promising compound that stimulates the hypocretin receptor was reported last year.

Conclusion

You can learn a lot about a person by meeting their best friend. As we learn more about dogs we’ll learn more about ourselves—our history, our language, and our idiosyncrasies. In addition to being loving and devoted pets and disciplined service animals, I hope dogs can increasingly act as research subjects. I think research can be ethically and thoughtfully performed on dogs and I hope dogs’ contribution to science, will further elevate our respect for them and treatment of them. I mean, when’s the last time a cat contributed to science? (Actually there’s an interesting story about that, but I’ll leave it for another day.)

If you liked this article, please share it and follow me. If you didn’t like this article, but you like dogs… share it anyway? See ya’ll next week.

—-

[1] Authors did earlier tests to calibrate the tasty food given, to ensure that wolves and dogs showed equal preference for the food and they were only measuring preference for risk.