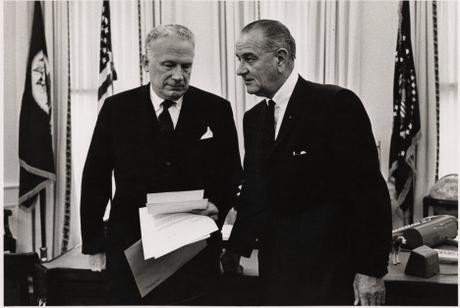

George W. Ball and President Lyndon Johnson, ca. 1965. Image credit: George W. Ball Papers, Princeton University.

[Pauling and the Vietnam War, Part 4 of 7]

Almost as soon as he had received it, Linus Pauling sent a copy of Ho Chi Minh’s letter of November 17, 1965 to U.S. President Lyndon Johnson. While the letter contained some “strongly worded” rhetoric about the United States, Pauling wrote, these were to be expected from the leader of a small country that was undergoing significant aerial bombardment from a world power.

In Pauling’s view, the more loaded statements made in the letter were relatively unimportant. Rather, Pauling highlighted Ho Chi Minh’s aspirations for peace as the crux of his response, pointing out that his four-point prescription for resolution was not described as a prerequisite for the initiation of negotiations. Indeed, Pauling took pains to note (perhaps with some measure of concern) that Minh had not called for negotiations as a means to achieve a peaceful resolution at all. Nonetheless, he believed that the Vietnamese leader’s hopes for peace in his country could prevail if the United States initiated negotiations for strategic withdrawal and cease-fire.

The response from Washington to Pauling’s letter came not from President Johnson himself, but from the administration’s Under Secretary of State, George W. Ball. Ball’s stated position was much the same as that conveyed to Pauling and Corliss Lamont by McGeorge Bundy in 1962. Ball wrote that, in its dealings with the North Vietnamese, the United States government had given its support to “every one of the many efforts to open the way to unconditional negotiation.”

In this, Ball implied that the inability to negotiate a cease-fire was not the fault of the US, but rather the doing of the National Liberation Front, or perhaps the North Vietnamese government in Hanoi. Pauling questioned this implication, arguing instead that since the United States did not view the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam as a legitimate political entity and viable negotiating partner, the U.S. shared at least some culpability in perpetuating the war.

Though addressed by George Ball, Pauling responded directly to President Johnson:

The possibility that this belief is correct is supported by the last paragraph in the letter sent to me by Under Secretary Ball, which reads as follows: ‘We give the same support to your appeal. We hope it may help to persuade the government of Hanoi and the government of Peking that this conflict should be moved to the conference table.’ I am accordingly writing to ask you the following question: Does the United States government refuse to negotiate with all of the governments and parties concerned in the war in Vietnam, including the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, or is the government of the United States willing to negotiate with all of the governments and parties concerned in this tragic conflict?

The response to Pauling’s letter came, once again, from George Ball, and he did not directly answer Pauling’s question. Rather, Ball replied that the National Liberation Front was “exactly what its name connotes,” a front for North Vietnamese aggression against South Vietnam. From the perspective of the White House, the NLF held no standing under international law, enjoyed only coerced support from the people of South Vietnam, and had no ability to survive except as a tool of the regime in Hanoi.

“To this day, Hanoi is directing its activities and supplying it with essential men and materiel,” Ball lamented, adding that, “if the North Vietnamese regime were to decide to negotiate in good faith on an unconditional basis, it would find no difficulty in making a place for representatives of the Liberation Front on its own delegation.”

For the United States, the key term that might lead to negotiations was that the revolutionaries leading the resistance in South Vietnam speak at the negotiating table solely through the established leadership of the North Vietnamese government. Crucially, the American government claimed that it was willing to respect the conventions of the Geneva Accords, which both North Vietnam and the NLF also wished to see respected. Since both sides seemed to agree on this and yet no cease-fire had come about, Pauling concluded that the United States was not being honest in stating its support for a return to the 1954 accords.

Fellow Nobel Peace laureate Philip Noel-Baker, a member of the House of Commons in England, concurred. Noel-Baker wrote to Pauling to say that he “warmly” agreed with Pauling’s view that the point to be cleared up was whether or not Ho Chi Minh was making pre-conditions for the discussions about a cease-fire – such as a demand for the withdrawal of American troops – for negotiations to begin. Like Pauling, Baker and others in the British government believed that Hanoi and the NLF were more than willing to come to the table if they were allowed to do so. He concluded that it was “disingenuous of your Government and mine to throw doubt on the point.”

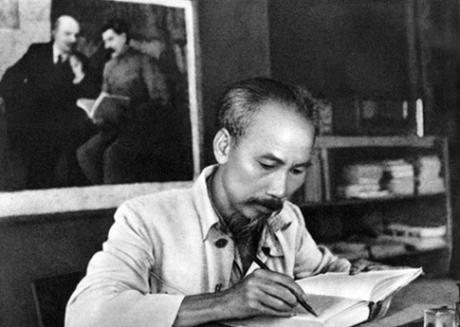

Ho Chi Minh in his study.

In December 1965, Pauling responded to Ho Chi Minh and reported that his letter of November 17th had been interpreted in a variety of ways. Depending on the point of view of the reader, different conclusions could be reached from the letter on the crucial point of whether or not the North Vietnamese were actually willing to enter into negotiations unconditionally. Pauling pressed his correspondent for more details:

I accordingly now write to ask you the following question: Is the government of the Democratic People’s Republic of Vietnam willing to begin negotiations that would lead to a cease-fire and a peaceful settlement of the Vietnam War without making any conditions as prerequisites to the beginning of the discussions?

As indicated in his exchange with Philip Noel-Baker, the core issue for Pauling was whether North Vietnam would require that American troops withdraw entirely, or require that all the conditions of the Geneva Accords of 1954 be upheld, before negotiations began.

In February 1966, another letter arrived from Hanoi. After apologizing for delays in his response due to difficulties in North Vietnam with communications, Ho Chi Minh addressed Pauling’s question:

The way to peace is: The United States must stop their aggression. It must strictly respect the fundamental national rights of the Vietnamese people as recognized by the 1954 Geneva Agreements on Viet Nam. That is the way which has been clearly pointed out by the March 22, 1965 Statement of the South Viet Nam National Liberation and the four-point stand of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam… If the U.S. Government really wants a peaceful settlement, it must recognize the four-point stand of the government of the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam…it must end definitively and unconditionally the air raids and all other war acts against the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam.

Another telegram, this one arriving in May 1967, reaffirmed this stance. The Vietnamese people, Minh declared, had produced their “Four Point Stand,” which embodied the main principles and provisions put forth by the 1954 Geneva Accords on Vietnam. “In my reply to U.S. President Johnson I made clear our goodwill and charter serious path to talks between DV and USA,” Minh communicated in the telegram. “USA must unconditionally stop bombing and all other war acts. But US Authorities do not want peace, and are intensifying war in both zones of Vietnam.”