Creation myths do psychological and cultural work. Because all known societies have creation myths, the number and variety is staggering. There are entire encyclopedias of creation myths and even dictionaries for creation myths. Given this seemingly endless variety, it is unsurprising there have been several kinds of efforts to impose order on the mass. Folklorists have categorized creation myths by thematic type. Philologists have arranged them into putative family trees, rooted by the hypothesized and long lost Ur-creation myth. Psychologists have classified them in correspondence with archetypes. Anthropologists have grouped them according to geography.

These efforts, while interesting and instructive, haven’t really grappled with the ways in which particular kinds of creation myths perform particular kinds of psycho-cultural work in the present. I have yet to see, for instance, an analysis of the ways in which the Edenic creation myth, in its structural and thematic details, frames a particular kind of individuated self and conditions a particular kind of collective culture. I suspect there are constitutive links between certain kinds of myths and certain kinds of identities. Identifying and tracing these links would seem to be a fruitful task but may be much easier said than done.

If links between particular kinds of myth and particular kinds of culture exist, the search for connections would begin with a thematic classification and mapping of the myths. This has been done for the creation myths of North American Indians. Anna Birgitta Rooth examined over 300 creation myths collected from North American natives and discerned 8 thematic types:

1. The Earth-Diver: this myth involves some being, often an animal, who dives to the bottom of an ocean to get sand or mud from which the earth and its denizens are created. It is found all over North America except for Arizona and New Mexico (i.e., the Puebloan area). Interestingly, the earth-diver creation myth is also widespread in Eurasia.

2. The World-Parents: this myth tells of a sky-father and earth-mother who jointly produce the earth and all living things. This usually involves the earth-mother giving birth and the fertility symbolism is heavy. This myth is found primarily in California, Arizona, and New Mexico. Similar myths can be found outside of North America in Japan and Polynesia.

3. The Emergence: this myth involves a hole in the earth or a cave from which humans and animals emerge to the present world. It is found primarily in the southwest Puebloan area with some spillover the the adjacent Plains. This is the primary form of creation myth found in Meso-America.

4. The Spider as First Being: in this myth the spider is the first being who spins a web that holds the earth together or makes it firm and thus makes it possible for other beings to exist on it. How these other beings come into existence is highly variable, but the spider is at the center of the entire cosmology. Versions of this myth can also be found in south America and China.

5. The Fighting or Robbery: this myth recounts the heroic deeds of a culture hero or transformer who steals the earth and its creations from greedy, pre-existing beings who have been hoarding for themselves. The transformer then gives these gifts to humanity. This is the most common form of creation myth among Northwest Coast Indians and finds parallels in northeast Asia.

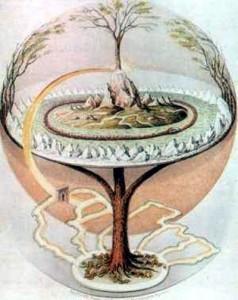

6. The Ymir: in this myth the world is created from the corpse of a dead giant or a dead man or woman. The skull is made into the sky, the bones become rocks, the hair becomes vegetation, and the blood becomes water. It is found throughout the North American continent. It is similarly widespread in Eurasia, and has interesting parallels with the Edenic myth.

7. The Two Creators Contest: this highly varied myth involves two creators, often siblings or relatives, who engage in a contest to “make” the best things with the result being the creation of the world and its contents. In some variations the world is created as a byproduct of a contest between the two. This myth is found in all areas of North America and has parallels in Asia.

8. The Blind Brother: this myth tells of two brothers who rise from the depths of the ocean bringing people with them. One brother tricks the other in a way that results in blindness; the blind brother in his anger then visits hardship on the people who have come to earth. This myth is found only in southern California and Arizona, and it told in adjacent parts of Mexico. Its distribution seems limited to these areas.

Rooth includes maps for each creation myth type showing where they can be found; although she doesn’t provide a single comprehensive map, a composite overlay would show that the myths have geographic clusters but don’t seem to correlate to any particular kind of culture (i.e., woodlands, coastal, horticultural, nomadic, Plains, Puebloan) or language area. As a cultural diffusionist writing in the 1950s, Rooth does find some attenuated connections which she describes in very general terms.

Her classifications and maps clearly indicate a complex history of migrations and contacts. The latter has resulted in several kinds of syncretic creation myths, many of which can be found in roughly similar forms outside of the Americas or in the Old World. It would take a tremendous effort to test the hypothesis that certain kinds of cultural structures correlate with certain kinds of creation myths. It could be done using the Human Relations Area Files, which codes for cultural variables but not necessarily for kinds of creation myth.

Because I don’t think this will be done anytime soon, where does this leave us? Probably nowhere. I can’t discern even the barest hints of a relationship between the structure of these societies and types of creation myths. What I have learned is that the Edenic myth, though dominant in some parts of the world, doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface when it comes to types and varieties of creation myths. They seem limited only by the imagination, which is to say not limited at all.

Reference:

Rooth, Anna B. (1957). The Creation Myths of the North American Indians Anthropos, 52 (3/4), 497-508