By Alan Bean

By Alan Bean

I published this essay almost three years ago, but it is still generating a lot of interest so I thought it deserved as second go-round.

American liberals can’t fathom the appeal of the Tea Party phenomenon. Here we are, struggling to recover from a recession created by massive tax cuts, military adventurism, and an under-regulated financial sector and what are they asking for: more tax cuts, even less government regulation, and more military spending.

Moreover, this message sells in the heartland, big-time.

By every standard of rationality, progressive politics should be enjoying a renaissance. The alternative has been weighed in the balance and found wanting. And yet politicians aligned with Tea Party rhetoric are winning elections and shaping the political agenda. How can these things be?

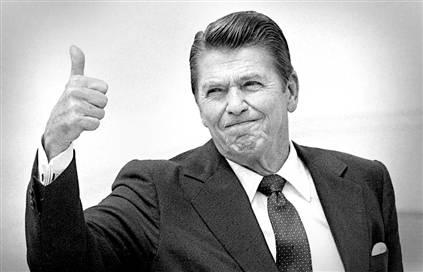

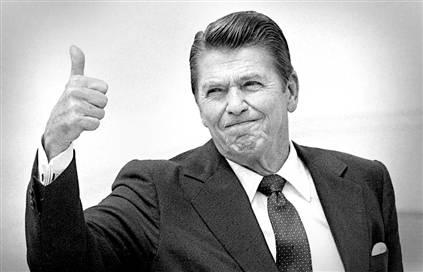

Progressives were equally amazed by the stellar political career of Ronald Reagan. There was little rational argument in his speeches, his facts were frequently askew, and he enjoyed little support in the halls of academe. Yet he won two elections and is revered by many Americans as the greatest president of the 20th century.

Walter Fisher’s narrative paradigm

Walter Fisher, a professor of communication arts at the University of Southern California who published his most influential work during the Age of Reagan, is known as the father of the narrative paradigm (you can find a seven-minute video summary of his thought here.) Academics and educated liberals misread American politics, Fisher taught, because they subscribe to a rational-world paradigm. To wit,

- Humans are essentially rational beings

- The primary mode of human decision-making and communicating is rational argument

- Different rules apply in different fields: legal, scientific, legislative, public and so on

- Rationality is a function of subject-matter knowledge, argumentative ability, and skill in employing the rules of advocacy

- The world is a set of logical puzzles that can be solved through appropriate analysis and the application of reason.

The rational-world paradigm, in Fisher’s view, requires the participation “of qualified persons in public decision-making” and assumes that experts will call the shots. The logical consequence has been “to restrict the rational-world paradigm to specialized studies and to treat everyday argument as irrational exercise.”

Walter Fisher had no bone to pick with rationality, but he saw human beings as storytellers rather than thinking machines. To be effective, even logic and rational argument must take narrative form. His narrative paradigm featured five key presuppositions:

- Human beings are storytellers

- The primary paradigm for human decision-making and communication is “good reasons”

- Good reasons are influenced by history, biography, culture, and character

- Rationality is determined by coherence, narrative probability and narrative fidelity

- The world is a set of stories from which people choose

Human beings are rational, Fisher held, unless they are mentally defective. Formal logic and discursive argument require specialized training, but normal people learn from infancy how to evaluate ideas using what he calls “narrative rationality.” Intellectuals or experts, Fisher believed, function best as counselors as opposed to tellers of “a story that ends all storytelling.” Experts, to be effective, must make themselves “subject to the demands of narrative rationality.”

“Good reasons” for adopting any rhetorical message are “inexplicably bound to a value–to a conception of the good”. Good reasons are “good” in a moral sense and that means a good reason isn’t necessarily effective or persuasive. Good reasons are rooted in fact, they are relevant to the issue at hand, they are tied to positive consequences, they conform to the life experience of the audience, and they plug into transcendent value–the highest good an individual can imagine.

Walter Fisher

We are able to communicate across cultures, genders, races and epochs, Fisher said, because our good reasons are communicated through narratives or stories which are universally intelligible. “The operative principle of narrative rationality is identification rather than deliberation.”

Stories must also be shaped to fit the self-conception of a specific audience. “Any story, any form of rhetorical communication,” Fisher wrote, ”not only says something about the world, it also implies an audience, persons who conceive of themselves in very specific ways. If a story denies a person’s self-conception, it does not matter what it says about the world. In the instance of protest, rival factions’ stories deny each other in respect to self-conceptions and the world. The only way to bridge this gap, if it can be bridged through discourse, is by telling stories that do not negate the self-conceptions that people hold of themselves.”

The narrative politics of Ronald Reagan

The narrative politics of Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan, and the Tea Party movement that was created in his image, are rooted in stories that connect with the values and the self-perception of ordinary people. Reagan had an intuitive grasp of narrative rationality and worked it to his advantage. Walter Fisher’s most influential book, Human Communication as Narration: Toward a Philosophy of Reason, Value, and Action was published in 1987, just as the Great Communicator was about to bow off the political stage, and Fisher devotes an entire chapter to an analysis of Reagan’s political success.

“One needs to consider Reagan’s story and his character,” Fisher believed. ”These are matters neglected in the rational-world paradigm, but they are crucial to an understanding of Reagan’s rhetoric.”

Reagan’s story has its roots in nineteenth-century romantic democracy, the tap root of which was the common glorification of the ideal of individualism. This ideal was interpreted differently in different parts of the country, but it was at the heart of concepts fostered by the romantic Old South, the romantic East where the principles of capitalism were celebrated, and the romantic West where the frontier beckoned the pioneers and captured the imagination of all America in folktale and legend.

Fisher leaned heavily on the research of Robert Bellah, the UC Berkeley Sociologist who had just published Habits of the Heart.

Bellah and his associates interviewed a large sample of middle-class Americans and concluded that individualism has two fundamental modes of expression: “a belief in the inherent dignity and, indeed, the sacredness of the human person” and “a belief that the individual has a primary reality whereas society is a second-order, derived or artificial construct, a view we call ontological individualism.” This second view coincides with traditional heroism–”a man’s got to be what a man’s got to be”–and Reagan’s notion that America and its people are essentially heroic. Reagan’s story consistently reinforces this belief: act according to our heroic nature and our destiny is assured. Reagan’s popularity stems in no small part from the coherence and felt fidelity of this story.

It was this view of America as a nation of heroes that resonated so powerfully in a nation surrounded on every side by indications of decline.

In Fisher’s view, “The 1980 election was a contest between argument and narrative as individuated forms of address. The pragmatic ideas became overwhelmed by the romantic images.”

Rational-world critics could never understand why apparently rational people felt so positive about a man who rarely attempted a rational argument. It wasn’t just Reagan’s evocation of the America myth of heroic individualism that made him popular, he also tapped into key features of the American Dream.

The American Dream is actually two myths shared in some degree by all Americans. There is the materialistic myth of individual success and the moralistic myth of brotherhood. It would be hard to find an American that has no allegiance to these two sets of ideals/aspirations . . . The materialistic myth fosters a concept of freedom to do as one pleases; the moralistic myth stresses freedom to be as one conceives oneself.

Ronald Reagan succeeded by emphasizing the materialistic side of the American Dream; Barack Obama, it could be argued, established his political hopes on the moralistic myth of brotherhood, the primary theme of his electrifying speech at the 2004 Democratic Convention. Although every successful president must appeal to both materialism and brotherhood, Reagan put almost all his rhetorical eggs in the materialistic myth basket. ”Salient features of this view of government,” Fisher says, ”are a belief in natural law, the Calvinist [work] ethic, moral individualism, a ‘weak’ state (the best government is one that governs least), and the efficacy of competition.”

The surprising appeal of the Tea Party movement is tied to precisely this message. Government doesn’t create jobs, conservative leaders tell us, business does. This rhetoric flows from the narrative of the American entrepreneur, sleeves rolled up, taking charge, adapting instantly to challenge and change, always probing for the next opportunity to expand, to prosper. On this man’s fortunes (and it is always an individual male, never a female or a faceless corporation) our salvation depends.

“The taxing power of Government,” Ronald Reagan told America, “must be used to provide for legitimate Government purposes [that is, making the world safe for the entrepreneur]. It must not be used to regulate the economy or bring about social change. We’ve tried that and surely must be able to see that it doesn’t work.”

Ronald Reagan, and those who claim his legacy, appeal to the same values that are extolled in adult Sunday school classes across America. Each value was firmly enmeshed in a narrative web.

The values attendant on family, work, neighborhood, peace, and freedom are individualism, self-reliance, efficiency, practicality, and success. The enemy, the devil who denies these values and thwarts those who would live by them, is the government. As Reagan said in his Acceptance Address, the American system “will continue to serve us in the future if our government will stop ignoring the basic values on which it was built and stop betraying the American workers who keep it going.” Government, he declared in his 1980 Inaugural Address, “is not the solution to the problem, government is the problem.”

While Ronald Reagan embodied heroism, Jimmy Carter embodied goodness. The problem, for Carter, is that Americans have always found heroism more inspiring than goodness. In fact, although it is rarely put this indelicately, goodness gets in the way of the heroic American. It is in this connection that Fisher cuts to the beating heart of American politics:

Whereas the image of “goodness” appeals to conscience, to one’s sense of ethical being, the image of the hero appeals to ego, to one’s conviction that one can face hazards or hardships and prevail. The “ethical person” is; the “hero” does. Conscience is not always a source of joy or pride. At worst, ethical principles brought to consciousness make one feel guilty; at best, ethics creates self-examination and perhaps self-doubt. The “hero,” on the other hand, is led to feel good about himself or herself no matter the adversity. In a time of distress and uncertainty, the hero image is as rhetorically efficacious as any image one might conceive . . . In a profane world, the hero is God. [My emphasis]

What’s the take-away for progressives?

Rational-world argument isn’t enough

We must get over our fixation with factually correct analysis and rational argumentation. This is great stuff within the academy, but it doesn’t translate well to non-specialists, that is, the people who vote. If the goal is to connect with main street Americans, we must learn to wrap our nifty arguments in narrative. Stop arguing and start telling stories. Discover the power of metaphor and the finely turned phrase. What is the progressive equivalent of “Government is the problem”?

If we want people to pay attention to our studies, graphs and policy arguments we need to ground them in a compelling narrative.

We must appeal to a moral narrative

Secular policy wonks tend to be cynical and secular. Enough with the sermons, we say, just show me something that works. But liberal politics is deeply moral; it’s about helping poor people, lifting up the weak, encouraging the forgotten and neglected people who fall through the cracks. We are the people who believe things can be better, that all people matter. We believe that America is great when America is good. The moral quest, especially in America, will almost always be wrapped around a religious narrative.

Religious narrative is suspect on the left. If the only religion you see is on the television and the only religion you hear is on the radio, despair is entirely appropriate. Fortunately, that kind of religion is an aberration designed to make the world safe for hero-worshippers caught up in radical individualism and the materialistic side of the American dream. Check out the original narratives, the stories, on which most religions are based and you enter a world dominated by the values of love, justice, forgiveness, equality, understanding and hope. Religious narratives are moral narratives–stories about goodness.

Our moral narratives must tap into genuine passion

Passion doesn’t have to be sleek, self-indulgent or sensual. Genuine passion puts a catch in your voice, it takes your breath away, it evokes tears. If we can’t wrap our facts and figures around that kind of moral fireworks we’re dead. We either inspire America with a moving vision of radical goodness, or we give up the game.

Goodness narratives come with built-in problems, no question. There is so much in the American story that is tragic, even shameful. We on the left have stacks of studies, graphs and historical exposes proving that Americans are very bad people. The more effectively we drive this point home the more we send ordinary Americans fleeing into the arms of Ronald Reagan and his political progeny.

“What do you want to hear about,” the conservative rock stars ask, “guilt or greatness?” We can’t fight that kind of ideological denial with charts and graphs; we need narratives that hook moral passion.

We must tailor the truth to the self-conception of our audience

Ronald Reagan believed his message with all his heart and soul, and it showed. Liberals have spent the last three decades pointing out the flaws in the great man’s political vision and we’re been right every time. On the rational-world score board we’re way ahead; but when they count the votes we usually lose. We are very good at telling people why the other guy is an idiot; but we have no shining alternative on offer, something we believe so deeply that it shapes who we are and drives everything we do.

We need to tell the truth in ways that are consistent with the self-conception of normal Americans. “You know the way you are? Well, stop being like that” is a really bad political message. Reagan exploited the materialistic side of the American dream and Democrats are only successful to the extent they tap into the moral side of American mythology.

Here’s the message, “You know the way we are as a people; eager to help the poor and the helpless; putting out the welcome mat for people from all over the world; willing to accept people as people regardless of language, nationality, skin color or religion; eager to make our country work for everybody? These are the values that make us great. Sure, we fall short, often in tragic ways; but we never take our eyes off the goal. That’s the kind of America I want to live in, and I bet you do too.”

Ronald Reagan never attempted a full frontal assault on the moral side of the American Dream. He never took issue with the sentiments embedded in the famous words of Emma Lazarus: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore.” America’s moral myth was too deeply rooted in the national psyche to be messed with, it could only be ignored.

Similarly, dumping on the materialistic myth of hard work, rugged individualism, personal responsibility and success is a fool’s game. These ideas are woven into the American identity and no one can change that. The best we can do is to shift the emphasis from the materialistic myth to the moral myth. Both sides of the American Dream elicit nods of approval because both are familiar, banal, inevitable, part of the inherited American furniture. Sure, relating our message to the moral side of the American Dream is a form of domestication, but it is absolutely necessary.

If Barack Obama preached the moral side of the American Dream and lived as if he really believed it, he too would be ridiculed as a lightweight on both the right and the left. But in the process he would make his political opponents look cheap, mean and ugly.

If we want to transform American politics and practice we must tell stories we believe in. That means moving from rational-world pragmatism to a narrative vision. It means finding a moral narrative rooted in genuine human emotion. It means tailoring the truth to the self-conception of our audience.