However, watching 'Asteroid City ' did give me the inspiration for this week's blog about catalogues - because up till then I confess I was feeling somewhat stumped. And by the way, it was not for nothing that Wes Anderson and his fabulous cast received a ten-minute standing ovation after the film was screened at the Cannes Festival in May. (I'll take it over 'Barbie - the movie ' any hard day's night.)

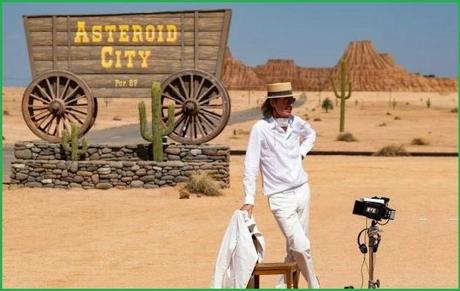

director Wes Anderson on the set of Asteroid City

Without divulging too much of the plot, suffice to say that the action takes place in 1955 in the (fictional) American desert town of the film's title, a place famous for its meteorite crater. The itinerary of the annual Junior Stargazer/ Space Cadet convention (organised to bring together students and their parents from across the country for fellowship and scholarly competition), is spectacularly disrupted when observation of a rare astral event reveals something totally unexpected. (Enter the alien.)In an attempt to pinpoint the origin of this world-changing phenomenon, there is much recourse to star maps (like the one on the observatory wall - see below) and star catalogues - which is the jumping-off point for today's blog.

Asteroid City observatory with star map on the wall

Obviously enough, star catalogues are tabulations of astronomical objects, usually grouped by type, morphology, origin et cetera. They have been compiled from mankind's earliest days and the first ones were literally inscribed on clay tablets by the Ancient Babylonians of Mesopotamia in the 2nd millennium BC, followed chronologically by the Ancient Greeks, Chinese, Persians and Arabs, sometimes but not invariably accompanied by illustrated star charts. Interestingly, there is no evidence that the Ancient Egyptians created star catalogues though they did produce star maps which often adorned the ceilings of their tombs.Of course the majority of early star catalogues were limited by observational capability and, as with the accompanying star maps, could be somewhat subjective. Nonetheless, they were impressive compilations, accurate enough to assist in divination, husbandry, navigation and as a means of identifying shifts in the heavens.

The invention of the telescope rapidly advanced our ability to observe and catalog astronomical objects and with the more recent advent of powerful observatories and the arrival of radio-telescopy, it has become customary to give stars numbers rather than names.

section of a star map

My all-too-brief research into star catalogues has identified a plethora of modern ones. There have, for instance, been dozen "full sky" catalogues created in the last 200 years by different scientific institutes. The most comprehensive of all (and I use that term very loosely) are the three Gaia catalogues (DR1, DR2, DR3) being made by the Gaia space telescope listing billions of stars. How the minds of those Ancient Babylonian and Greek astronomers would blow if they could see how far we have come in terms of stellar knowledge!Then in addition to the comprehensive catalogues, there is another raft of specialist star catalogues listing specifically double-stars or carbon stars or stars of a particular magnitude or even simply 'nearby stars'. Then there are trigonometric parallax catalogues and proper-motion catalogues, manifold niche tabulations enough to make this modern head spin! All digital nowadays of course, because of the sheer volume of data, and much of it in the ether. I like to think of it as the Cloud Of Knowing.

To conclude, here's the latest from the imaginarium, probably still evolving if I'm honest...Holes In HeavenCall it numinousfor how can dark matterso long as there areholes in heaventoo brilliantly numerousfor terror's insinuating fingers to obfuscate?

Thanks for reading, S ;-)

Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to Facebook