READ THIS BOOK

READ THIS BOOKLost? Confused? Me too. I was just as surprised to be diagnosed with breast cancer at the ripe ol’ age of 26 as most of my friends and family were.

Here are a few things I’ve learned so far about what’s helpful and what isn’t when it comes to receiving support from people. Obviously, I only speak for my own experience here, but you’d probably hear a lot of similar things from other cancer patients.

1. Read/listen carefully to what we say.

Since I draw so much of my strength from writing, I turned to it immediately when I got my diagnosis–not just to talk about my feelings and experiences, but also to express what I needed from people who wanted to help. I wrote out detailed instructions and set clear boundaries. (As did my roommate, who started a Facebook group with some of my other friends and used it to coordinate support.)

Nevertheless, both of us were often swamped with questions that could easily have been answered by reading what we’d posted. People repeatedly asked for my address, gift preferences, dietary needs, and other stuff that my roommate had clearly addressed in multiple posts. It was, honestly, really frustrating. I understand that all of this is hard and that paying attention to written text can be hard and being a human is hard. But surviving the first few weeks of a cancer diagnosis is especially hard, so please make it easier on your newly-diagnosed friend by being attentive to what they’re telling you.

2. Don’t inundate us with irrelevant and overly-specific questions about gifts.

On a related note, it was pretty overwhelming when, within the first couple days of my diagnosis, comments and messages like these started pouring in: “Is there anything I can get you? Do you need hats? What color hats? What type of yarn? Do you like letters? Would it be okay to send a card? What’s your address? What kind of food do you like? Can I send cat photos?”

I 100% understand where this is coming from. People want to help, and they don’t want to help in ways that are harmful or unwanted, so they ask lots of questions about exactly what kind of help would be welcome.

But guys. I don’t care what color hat. Those first days, when I was still waiting for all my test results, I was facing the fact that I could be dying. I could find out that it’s metastatic, that I have a few months or years left, that I’m going to have to tell my 12-year-old sister that I’m fucking dying. I wanted to take these well-meaning people by the shoulders and shake them and tell them that I don’t care what color hat.

If you’re already making/doing something specific, such as knitting a hat, it’d be more helpful to ask, “Is there anything I should keep in mind when making this for you?” That’d be a good place for me to ask you to avoid Breast Cancer Pink, for instance. (Although, again–I really don’t care about stuff like that very much right now.)

Otherwise, I’d suggest directing these questions to a caregiver, such as the person’s partner(s), family, or closest friends.

3. And about those cat pictures…

I’m going to reiterate that I’m only speaking for myself here, and not for any other survivors or anyone else living with a serious illness, but boy howdy did it ever rub me the wrong way when people immediately wanted to send cat pictures following my diagnosis. Cat pictures are nice for when you’ve had a stressful day at work or you need to forget about political news for a bit. “Sorry to hear about the cancer, here’s my cute cat” doesn’t really work.

4. No medical advice. None. Nada.

In my opinion, giving unsolicited medical advice when you are not that person’s doctor is always wrong, for a variety of reasons. However, it’s especially wrong when the medical condition in question is both deadly and very poorly understood by most laypeople. (Seriously–I’ve learned a ton about cancer these past few weeks that I never would’ve known otherwise.)

For example, someone literally tried to tell me that there’s doubt that a prophylactic mastectomy is effective for preventing breast cancer. But according to all of my doctors and all of the information I could find on reliable websites, people with a genetic predisposition to breast cancer can reduce their risk by 90% if they have that surgery. Because I have the BRCA-1 gene mutation, my risk of developing a second breast cancer within 15 years is otherwise 33%. (My lifetime risk of developing breast cancer at all was 55-65%. So yeah, I wish I’d known that and gotten the surgery years ago.)

So please do not give me advice that could literally kill me. Thanks.

5. Keep talking to us about your own life and problems.

A lot of times when someone gets diagnosed with a serious illness, people around them start feeling like they shouldn’t talk about their own (comparatively) less severe issues. Please do talk about them! I mean, obviously take your cues from the seriously ill person, but in my experience, it’s comforting to listen to friends vent about work or people in their lives or whatever. Checking in before/while dumping heavy stuff on someone is always a good idea whether they have cancer or not.

6. Resist the urge to relate our struggles to yours.

This is often an issue when someone’s talking about a shitty thing they’re going through, but when it comes to stuff like cancer, it’s especially relevant. The morning sickness you had during pregnancy is not like the nausea folks have during chemo. Your choosing to shave your head for aesthetic reasons is not like having your hair fall out because cells in your body are being destroyed. Choosing to get breast implants is not at all like having to have a mastectomy and reconstruction. And so on.

Sometimes, folks with other serious illnesses besides cancer do have very relatable experiences. (For instance, I met someone who has to have chemo because of a totally non-cancer condition.) Otherwise, just center the experiences of the person who’s going through the serious illness.

Note that I do not mean it’s wrong to simply say, “Ugh, yeah, I have nausea every day from my psych meds” or “That sounds a lot like me when I was pregnant.” Of course some cancer-related experiences are going to resemble some non-cancer related experiences.

Where comparisons fall flat is when you’re trying to comfort or reassure someone, or when they’re trying to talk about their cancer and you keep changing the subject to your pregnancy. If I’m terrified of reconstruction surgery, you’re not going to be able to reassure me by reminding me that some people (whose choices I respect but completely do not understand, by the way) choose to get implants, because that experience is going to be completely different.

7. Remember that most side effects of chemo are invisible.

Cancer patients often talk about the dreaded “chemo brain,” which is the shitty mix of mental fog, fatigue, and executive dysfunction that often happens during chemo. Just because we’re not vomiting or bedridden doesn’t mean we’re not experiencing some pretty serious side effects.

For me, this means having a lot of trouble with time management. Sometimes time seems to pass way more quickly or slowly than I would expect. I have a very hard time processing things like “when do I need to start getting ready in order to leave early enough to arrive at Thing on time.” I’m pretty much late to everything these days. The fact that I’m often so tired that standing up feels impossible doesn’t help.

I try not to keep anyone waiting for too long, but it helps a lot when people are able to be flexible.

8. Look for the less obvious ways to help.

When someone gets diagnosed with cancer, people usually gravitate towards the most obvious, visible ways to help: making meals, giving gifts, and so on. I also got tons of invitations to come hang out at someone’s place. However, the most helpful thing for anyone whose condition involves fatigue and needing to sleep, eat, or take medication on very short notice is offers to hang out near my home, not yours.

Even when people offer rides (which is very helpful, by the way), there’s always the potential discomfort of having forgotten my anti-nausea meds at home or desperately needing a nap or getting hungry in someone’s house and not knowing what to do or running out of tissues. I love offers to go to a restaurant or coffee shop near my place, or hang out at home.

A good question to ask someone is, “Is there anything you need that folks haven’t been offering to help with?”

9. Please don’t take it personally if we don’t take you up on your offers to put us in touch with your cousin/grandmother/friend-of-a-friend who has/had cancer.

Sometimes it’s helpful to talk to people who’ve been through it; sometimes it’s not. Regardless, that’s why support groups exist, as well as tons of one-on-one peer support services. I’m not really comfortable with calling a total stranger on the phone to talk about cancer, especially when it’s someone at least twice my age (which it often is).

Every cancer is unique, but the experience of young breast cancer patients in particular is often quite different from that of older people, because ours tends to be more aggressive and difficult to treat, and we tend to have less material/social resources and support than older survivors do. Many of the older survivors I talked to told me quite cheerily that they simply had surgery and were back to their normal lives soon after. That’s not at all how it’s going to be for me–I have to have chemo, then surgery, then possibly radiation, and then ten years of hormone blockers, plus being constantly vigilant for symptoms of ovarian cancer, which I’m also at increased risk for and which has no reliable early detection methods. Not super helpful to talk to people who didn’t have to deal with most of that.

10. Mind the boundaries.

There’s something about getting diagnosed with cancer, and talking about it openly, that makes some people assume that our relationship is much closer than it really is. It was weird to have people I barely know telling me that they hope I visit their city so we can hang out, or to offer help with stuff that’s honestly really personal and not at all a part of my life that I’d normally share with them. (For instance: decisions about my breasts and what to do with them.)

It’s true that there are certain boundaries that come down out of necessity when you’re going through a serious illness; for instance, my parents now know a lot more about my health, body, and lifestyle than they would’ve known otherwise. But that’s because my parents are my primary caregivers. They need to know that stuff in order to take care of me. You, random person who added me on Facebook because you like my writing, are not my primary caregiver. If you wouldn’t normally talk to me about my breasts or expect me to include you in my travel plans, don’t do it now, either.

11. Unless otherwise stated, assume that your gift/gesture is received and welcome.

In most situations, it’s rude not to reply with a “thank you” when you’ve received a gift from someone. When you’re newly diagnosed with cancer, it’s not. When people message me with “Did you ever get my package?” or “So was that hat I sent a good fit?”, the message I get is that I should’ve made sure to reach out and let them know that I received the gift and that I like it (whether or not I actually did like it), even when my days are a messy jumble of medical tests and treatments.

Personally, I take gratitude very seriously and I’m keeping a notebook of everything kind anyone does for me so that I can properly thank them later. (The key word there is LATER: when I’m not in the middle of chemo, probably.) But this isn’t something you should expect of your friend with cancer. This isn’t a normal situation, so normal rules of etiquette don’t apply. If you know that you wouldn’t be happy to give this gift or offer this help without the validation of a personalized thank you, don’t give it.

12. Assume that other people are doing what you’re doing.

While that’s not always true, it can help you avoid doing things that are going to frustrate your friend or make their life more stressful. The previous suggestion is a good example—one person asking if I’ve received their package may be okay, but multiple people asking gets really overwhelming. One person asking for detailed instructions on how to knit me a hat isn’t that big of a deal, but providing multiple people with instructions for multiple types of knitted items is way too much.

“What if everyone behaved the way I’m behaving” is a great question to ask ourselves in many situations because it’s a reminder that it’s not just about you, and your gift, and your need to be helpful, and your anxiety that your gift wasn’t appreciated enough.

For me, there’s no such thing as too many cards and letters, or too many texts that say “No need to respond to this, but I love you and I hope your treatment is going okay.”

13. Decide what kind of support YOU want to offer, and offer it.

It’s a cliche by now that “Let me know if you need anything!” isn’t a super helpful thing to say (not that I mind it—I just take it literally), but the way to really grok that is to understand that most struggling people would rather you help in ways that YOU want to help rather than turning yourself into a put-upon martyr at our beck and call. That’s not a dynamic healthy people like.

Ask yourself what kind of help would bring you joy to offer, and what kind of help you’re good at giving. Do you like mindless household tasks? Cooking? Taking care of pets and plants? Organizing fun distractions? Being a workout buddy? Figure it out, and then offer that.

Of course, there are some tasks that need to be done even if nobody particularly loves doing them. (Some horrific things I’ve heard about post-surgery recovery come to mind.) But these tasks are for caregivers, not concerned friends. My parents will be the ones to make the noble sacrifice here, not you.

14. Comfort in, dump out.

It’s a classic for a reason.

As I’ve reflected more on what I find helpful and what I don’t when it comes to receiving support from people, it occurs to me that the most irritating, upsetting, or tonedeaf responses are also the ones that seem like they’re covering up something else. I don’t want to presume and play psychoanalyst with people (that’s from 8 to 5 and with pay only), but sometimes it’s pretty clear that the person I’m interacting with 1) doesn’t know how to react when a friend has cancer, 2) realizes on some level that they don’t know, and 3) is panicking about this.

“Can I knit you something? Do you need hats? What are your favorite colors? Do you care which type of yarn?” often seems to be masking “I’m worried about you and I have no idea what I could possibly do to help.” “So did you get my package???” is maybe actually “I sent you this thing without asking first if you needed it and now I’m feeling awkward because maybe you didn’t need it or want it.” Unsolicited medical advice often means, “Cancer terrifies me and I’m trying to believe that if I do everything right it will never get me like it did you.”

Again–not necessarily. Not all the time.

But the further I get into this whole ordeal the more it feels like honesty and openness is the way to go–just like it is in almost every other situation we find ourselves in. I would rather hear that you care about me than answer a dozen questions about exactly how you can help. I would rather one silly card with poor handwriting than The One Perfect Gift That Will Make All This Go Away–because that doesn’t exist.

Send the card. Offer the practical household help. We’re all gonna be okay.

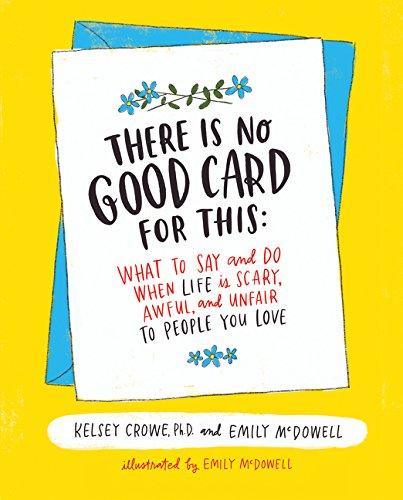

Two great books for those interested in learning more: There’s No Good Card For This and The Art of Comforting.