Hitchcock said something like: drama is life with the boring bits cut out.

If we’re to take him at his word, maybe we have less use for drama now than ever. Kiarostami is doing something different. I don’t think it’s radical to suppose there’s drama to what he does, but it’s surely life with the “boring bits” restored.

Kiarostami has talked openly about a cinema of naps (my own phrase,) suggesting that falling asleep during one of his films might add a level of experience. Tuning out becomes a radical type of “reading.” The work becomes a context to be lived and breathed inside, rather than a text to be read.

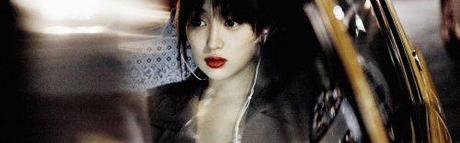

Such a philosophy is useful (at the very, very least) insofar as it gives us a context for understanding what’s so fun about a Kiarostami. Like Someone In Love may not be the director’s best, but it’s probably better than Certified Copy, a certifiably great movie that it seems decidedly in dialog with. (They were both made in countries other than Iran, and address cultural differences only in the sense that they are there. The rest is about characters, some of their relationships colored somewhat mysteriously. Such relationships are distinct but comparable to those that David Denby described as “perversely ambiguous” in Certified Copy, if that helps you.)

Like Someone In Love is not so unfathomably opaque as some critics would have you believe. It only looks opaque when you try to read it out in Bazinian, Freudian, Kantian or Ebertian terms. Watching the film is not so much like staring at an opaque text as like putting on a prickly, woolen sweater. Maybe a family heirloom, but more likely an artifact from an old relationship.

The greatest gift the movie has to offer is its willingness to wander (unless someone really has broken down the mechanics of why everything-follows-everything in this odyssey.) We get really intimately acquainted with our small cast of characters, and we have plenty of time to see them being themselves.

That’s the medicinal quality of Like Someone In Love: there’s plenty of time. That restoration of time, the concession or discovery that the passage of time need not be feared—but that it can be savored—is something that is whispered to you, in the audience, until you resort to frantic texting or else leave the theater for Dead Man Drop. In a culture where “time is money” can, occasionally, be uttered without irony, there is perhaps nothing so unnerving as a film that suggests just being alive may be enough. That looking carefully at the things that surround us everyday might be worthwhile.

I think some have been reluctant to talk about Kiarostami in terms of a contemporary contemplative cinema because of his metaphysical/ surreal bent. But you find that in Weerasethakul-World as well. There is a way of being surreal, of leaving the world outside the theater outside the theater, and all the while keeping a firm grasp on the reflexive consciousness of the viewer. Kiarostami’s new film is uncanny in much the same way that Certified Copy was; you hold your breath at first, wondering what secrets are about to be explained to you, and all the while they explain themselves to your untrained ears. Whether you start feeling the film a fourth of the way through, halfway through, or in its final moments is not entirely up to you– but I believe it is partially up to you. Think of this like listening to narrative music.

If you’re looking for a thematic statement, you might look elsewhere. But for introspection, sally forth.

Kiarostami reminds us that in a culture sluggish with the weight of anti-realism, of pop-fantasy and dependably body/mind/soul-alienating commercialism, a film that grounds itself in the rhythm of real-life and real-unknowability, is radical.

-Max Berwald