Book review.

In The Trip to Echo Spring: On Writers and Drinking, author Olivia Laing’s stated goal is “to know why writers drink, and what effect this stew of spirits has had upon the body of literature itself.” To which I can only say, best of luck. The goal is impossibly ambitious; the book itself a bit digressive and loosely organized. But Laing has harvested a satisfying litany of literary anecdotes related to drinking, and throws out a few of her own.

The writers she submits to scrutiny are F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, John Cheever, John Berryman, and Raymond Carver—all of them unambiguously alcoholic and, for most of their lives, resolutely in denial. Only two of them—Carver and Cheever—attained some measure of sobriety in their later lives. Fitzgerald died of a heart attack at 44, Hemingway and Berryman committed suicide, and Tennessee Williams either choked on a bottle cap or died of an overdose of pills. If any of that sounds deliciously romantic, than this is a book you need to read. “People don’t like to talk about alcohol,” Laing flatly states. “They don’t like to think about it, except in the most superficial of ways. They don’t like to examine the damage it does and I don’t blame them.”

Start with John Cheever, author of The Wapshot Chronicle, Bullet Park, The Falconer, and short stories, including “The Swimmer,” which begins: “It was one of those mid-summer Sundays when everyone sits around saying, ‘I drank too much last night.’”

“I cannot remember my meanness,” Cheever wrote poignantly, “because my recollections are damaged by alcohol.” It may have been literally true. Cheever suffered from aphasia, hallucinations, and seizures. On the basis of a CAT scan from 1975, Laing makes the argument that Cheever suffered from diffuse cerebral atrophy, and possible Korsakoff syndrome, a neurological disorder seen almost exclusively in alcoholics.

Tennessee Williams, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of plays such as A Streetcar Named Desire and The Night of the Iguana, also suffered a litany of medical problems directly related to alcohol, including peripheral neuritis in his feet. “Of course I would love to believe the good doctor,” Williams wrote, “but I don’t quite believe him.”

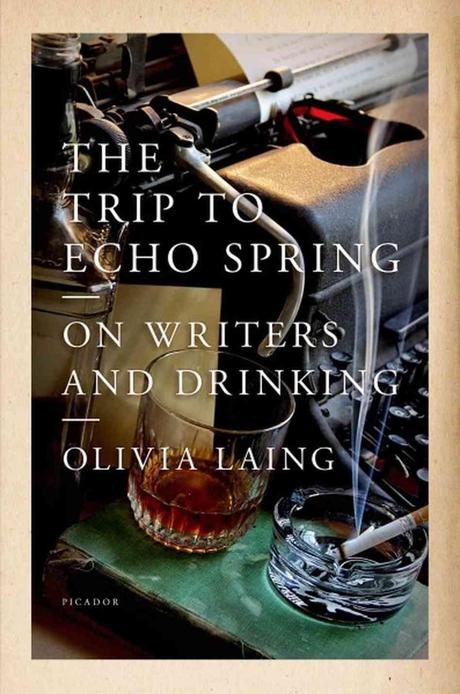

The title of Laing’s book comes from Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, in which Brick, the alcoholic son, frequently takes “a little short trip to Echo Spring,” referring to the liquor cabinet containing his favorite brain of bourbon. But awareness has a way of creeping in around the edges. In an early story that foreshadowed the play, the character of Brick says, “A man that drinks is two people, one grabbing the bottle, the other one fighting him off it, not one but two people fighting each other to get control of a bottle.”

Williams endured years of psychoanalysis and spent time in mental hospitals. He dutifully kept detailed notebooks: “Two Scotches at bar. 3 drinks in morning. A daiquiri at Dirty Dick’s, 3 glasses of red wine at lunch and 3 of wine at dinner—Also two Seconals so far, and a green tranquilizer whose name I do not know and a yellow one I think is called reserpine or something like that.” Now think of making it through a single day under that load of intoxicants.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, best known for his novel The Great Gatsby, wrote to his editor, Maxwell Perkins, in 1934: “I have drunk too much and that is certainly slowing me up. On the other hand, without drink I do not know whether I could have survived this time.” Laing notes that this ambivalence “could be interpreted as a refusal to see alcohol as a cause rather than a symptom of his troubles,” and in this Fitzgerald was by no means alone. For Fitzgerald, as for many others of the day, being “on the wagon” often meant restricting oneself to beer and the occasional glass of champagne. Fitzgerald, on the wagon at the rate of 30 beers a day, said that “when I swell up I switch to cokes.”

Laing provides us with a litany of these “excuse notes” from her writers: “I drink because it improves my work. I drink because I am too sensitive to live in the world without it. There are hundreds more of these,” she writes. In Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, she finds “an example of someone flat-out denying their own disease….” My own personal favorite is Hemingway’s letter in which he claims to be amazed and chagrined that alcohol, something “I could not have lived without many times; or at least would have cared to live without; was a straight poison to Scott instead of a food.”

John Berryman, poet, Pulitzer Prize Winner, National Book Award winner, and author of The Dream Songs, also battled depression and a tendency to fall down stairs, breaking arms, legs, and wrists. He served a stint as a creative writing instructor at the University of Iowa writing program, as would John Cheever and Raymond Carver. He ended up at the University of Minnesota, where he dried out repeatedly at Hazelden and other local clinics. Even Berryman’s most ardent supporters gave up on him. His chairman at the university said of him: “I concluded that the only John one could love was a John with 2 or 3 drinks in him, no more & no less, & such a John could not exist.” Berryman killed himself by jumping off a bridge in Minneapolis.

Let’s let Raymond Carver—poet, short story writer, and legendary drunk— have the last word. In a 1982 poem, he wrote:

And then…something: alcohol—What you’ve really doneAnd to someone else, the oneYou meant to love from the start.