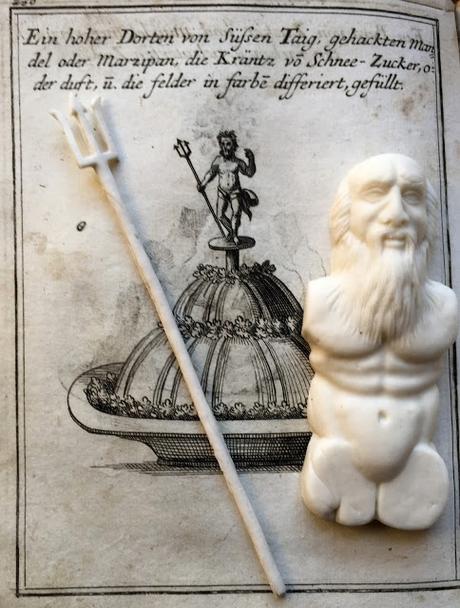

Behind the sugar moulded torso of Neptune and his trident is an almond cake, decorated with ornamental bands of snow sugar and surmounted by a dragant figure of Neptune. The illustration is in Conrad Hagger, Neues Saltzburgisches Koch-Buch (Augsburg; 1719). The sugarwork, (just two components of the complete sculpture) was pressed from a fruitwood mold from the same period (see last illustration below).

Trying to recreate food from the past is fraught with all sorts of problems. I remember my friend and colleague Peter Brears once telling me that he had frequently been served truly diabolical reincarnations of medieval food by historical re-enactors with loads of enthusiasm, but little knowledge or skill. He explained that one of the reasons he wrote his extraordinary book Cooking and Dining in Medieval England was to give a bit of help and direction to enthusiasts who enjoyed cooking within this culinary genre. As a museum curator who spent a long career dealing with objects, Peter like me, has always been an advocate of utilising period kitchen equipment in the recreation of old dishes. Some refer collectively to these redundant utensils as 'kitchenalia', a term I absolutely hate. I prefer to regard these objects as the silent culinary witnesses of our past food culture. Understanding how to use them can truly bring an ancient dish screaming and shouting into the modern world - a rebirthing experience that can be revelatory. Witness Mr and Mrs Early Stuart Gingerbread below.

Two white gingerbread figures made from a mold carved during Shakespeare's lifetime - with a wooden trencher and two late Tudor eating knives for good measure.

So I would like to say a little more about my methodology when it comes to recreating historical dishes. For instance, how on earth would one go about preparing the baroque almond cake surmounted by a sugar figure of Neptune at the top of this post? Or for that matter, the other early eighteenth century Hapsburg dishes (all from Conrad Hagger) illustrated below? The bakery is easy enough - just follow the recipes. But what about the rather tricky ornaments? One could attempt to model them from gum paste. But it would be far better to employ the equipment the bakers of the period used - skilfully carved wooden boards, which allowed you to knock out an impressive three dimensional figure of Neptune, Cupid or some other sugar deity. I have the basic skills to model figures like these, but if I did, they would be entirely twenty-first century creations, unavoidably watermarked with the zeitgeist of this moment in time. No matter how much of an effort I make to give them a period 'feel', they will only be in the realm of pastiche. But use a mold carved by a master of this period and the chances of creating something authentic are much higher.Those of us who attempt to recreate the food of the past, must deeply understand the culinary aesthetics of a particular period. I too have seen many attempts, particularly on television, where the creators look very pleased with themselves, but their creations are either heavily lumpen or resemble junior school art projects. We all need to up our game. Food ornamentation and presentation was closely related to the prevailing trends in the decorative arts. Of course, very few modern kitchens are equipped with these ancient examples of culinary material culture and not all dishes require their use. And of course, some of these objects are just too precious to use. But I have made it my vocation over a long lifetime to acquire a working collection, which now consists of thousands of objects from the fifteenth to the early twentieth century - enabling me to gain a much richer insight into this subject than I would get by just sitting in the British Library reading old recipes. Of course, once you own objects like this, you then have to learn to use them. And without much surviving instruction in the literature and with no living practitioners to show you how, it is often extremely difficult to master extinct skills.

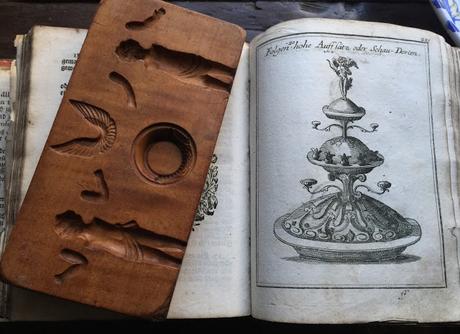

The wooden board on the right, dating from the first half of the eighteenth century, allows the construction of a figure of Neptune from different body parts. His legs and trident are on the other side of the mold. The boil on Neptune's buttock was created by a burrowing furniture beetle, probably back in the reign of the Empress Maria Theresa.The mold on the left, dating from the seventeenth century or earlier, was designed to enable the creation of a dolphin. I will be using both of these moulds in a demonstration workshop on baroque sugar sculpture at the Detroit Institute of the Arts in early February.

This eccentric pastry centrepiece of three ornamented 'dorten' also features candleholders. The Cupid embellishing its summit would have been made using a mold identical to this one.

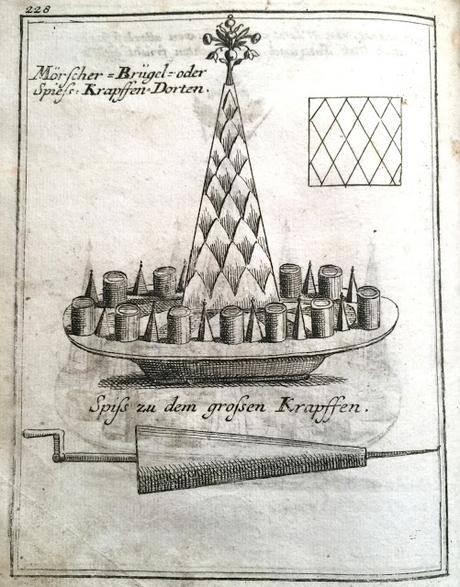

A Hapsburg Krapffen-Dorten - 'doughnut cake', the precursor of baumkuchen, which was once much more like the gateau à la broche still baked in front of the fire in the France on conical spits like this one illustrated in Hagger.

I hope this is the only time you ever see a valuable copy of Hagger's book on a kitchen floor, but I wanted to show you the impressive scale and cut of my 'Spiss zu dem grossen Krapffen!

Of course putting a collection together of this scope and quality - we are talking expensive antiques here - is a major investment. And then there is the problem of those that are just too fragile and precious to use - or dangerous - as in the case of early bronze and bell metal cooking pots and a few other utensils. Modern reproductions are the only answer here, but commissioning one-offs of these can be even more expensive than buying originals. Combined with my taste in expensive antiquarian recipe books this priority in my consumer behavior is the reason why I have never owned a decent car!

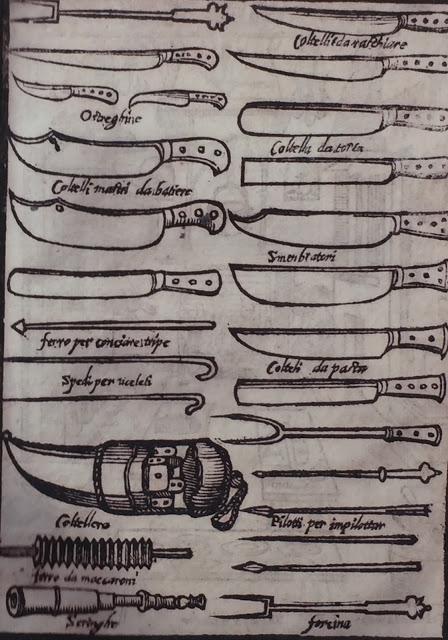

An embarrassment of riches. Two of my mid-sixteenth century bronze Italian pastry jggers, as illustrated in Bartolomeo Scappi. Opera (Venezia: 1621). Perhaps my favorite kitchen utensils of all.

Every kitchen should have a set of these, also illustrated in Scappi.

All the Scappi knives in the woodcut above in my kitchen. There are surviving kitchen knives from the medieval and early modern periods, but none are useable. The only answer is to commission quality reproductions. Of course knives like this do not make any difference to the appearance or authenticity of a dish. But what a wonderful insight into renaissance kitchen knife craft you get when you eventually master using them.

Gingerbread again. Eating knives are important to me too. They say so much about the culture of dining. This is an original English scale-tanged gudgeon-handled eating knife from c.1400. An everyday knife for an ordinary person, but very attractive. The rich with their gold, amber and ivory did not have a monopoly on beauty. Gudgeon is the root of the boxwood tree and was cheap. It sets off this medieval gingerbread perfectly. The brick red color is from the sanders powder in the recipe. Sanders is also made from the wood of a tree. The decorations are box leaves attached to the gingerbread with cloves.

Back to the King of the Ocean and friends. Components of a nautically themed baroque sugar sculpture on my work-table, which I will construct in a workshop at the DIA in Detroit in early February. I have to carry these fragile components in my cabin baggage. Have piece montée, will travel! I will post a photograph of the finished article.