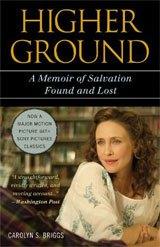

For the past few years I have been drawn to the spiritual memoirs of women. I suspect a deep disconnect prompts this interest. Religions—in this case primarily the monotheistic traditions—put a premium on fairness and justice, yet treat women as somehow outside these mandates. Women nevertheless respond to the human religious impulse somewhat more seriously than most men. This leads to a dissonance that surfaces in women’s memoirs. Carolyn S. Briggs’ Higher Ground: A Memoir of Salvation Found and Lost proved somewhat of an epiphany for me. In this story of an Iowa girl’s encounter and seduction into a Fundamentalist faith that never quite managed to smother her rationality, I recognized many aspects of her adopted religion from my own tenure in literalism. The real strength of Briggs’ account is her vivid recollections of how her own Fundamentalist mind worked. For many of us who’ve gone through that spiritual wasteland, dredging up those memories can be a harrowing experience. What shone through in Higher Ground, however, is how the fantasy-prone literalist imagination loses its tenuous hold on reality while promising deliverables that are always pushed off into the future. It is not a faith for the here and now.

For the past few years I have been drawn to the spiritual memoirs of women. I suspect a deep disconnect prompts this interest. Religions—in this case primarily the monotheistic traditions—put a premium on fairness and justice, yet treat women as somehow outside these mandates. Women nevertheless respond to the human religious impulse somewhat more seriously than most men. This leads to a dissonance that surfaces in women’s memoirs. Carolyn S. Briggs’ Higher Ground: A Memoir of Salvation Found and Lost proved somewhat of an epiphany for me. In this story of an Iowa girl’s encounter and seduction into a Fundamentalist faith that never quite managed to smother her rationality, I recognized many aspects of her adopted religion from my own tenure in literalism. The real strength of Briggs’ account is her vivid recollections of how her own Fundamentalist mind worked. For many of us who’ve gone through that spiritual wasteland, dredging up those memories can be a harrowing experience. What shone through in Higher Ground, however, is how the fantasy-prone literalist imagination loses its tenuous hold on reality while promising deliverables that are always pushed off into the future. It is not a faith for the here and now.

The non-denominational, yet Calvinistic, Briggs’ church home convinced the author, for some years, that she was inferior to her husband. There can be no doubt that this is “Bible-based” teaching, for the Bible is the product of a patriarchal age. Literalism grows more oppressive with the passage of time, for despite neo-con posturing, society is better for many than it was in the “good old days.” Fundamentalist traditions seek to reestablish the mores of the first century two millennia later, as if a simple transfer were possible. Society has offered progress for women while literalism is rife with regress. This double standard led to the loss of one of their own because over two thousand years much water flows under the bridge and brig.

Higher Ground is not an easy memoir to read—the accounts of those who experience repression seldom are. Religion is generally a conservative force in society, even if based on radical principles. The sayings of Jesus, for example, remain revolutionary even today, but they are often hidden behind the (male constructed) facades of organized religious movements. In school we teach our children that the sexes are equal, in Sunday school the opposite. Fundamentalism is not, however, in any danger of dying out. As Briggs demonstrates eloquently, the very thought process of a rational person is altered by it. Briggs leaves us guessing at what happened after the story ends but she has nevertheless contributed yet more evidence that demands a verdict. Until the judgment of fair and just can be rendered, religions will repeatedly be called to the witness stand.