You know, I thought I was crazy when I bid on a wedding dress two years ago and I wasn’t even engaged and marriage was not on my horizon. But because the dress was a simple silhouette and was made with a linen and silk eyelet, I justified my purchase by claiming it could be worn outside the confines of a wedding – “I could dip-dye it or make it into a skirt!” My character really came into question, not only by myself but by others, when a year after I won my first wedding dress, I bid on another. And there was no justifying this purchase. Poofy and featuring a giant bow on the skirt, the “sweeping taffeta ball gown” was ridiculous, a costume really, and there was absolutely no way it could be worn as everyday wear or even evening wear. I brushed off the laughs and questions I received for months afterwards with, “Well, if I have a Britney Spears moment and need to get married immediately, I’ll be ready with not only one dress but two!”

Until a couple of weeks ago, I was still muddled as to why I purchased the gowns and was saving up for the next opportunity to get another. Then it hit me – wedding dresses are the epitome of sewing. Just like a Porsche, they represent the highest level of craftsmanship and require both hand work and work done by machines. The amount of hours it takes to make a single wedding dress far exceeds double digits.

Wedding attire aren’t the only garments I have an intense hankering towards. Tutus also top my list of coveted clothing because, just like the wedding dress, their construction is incredible.

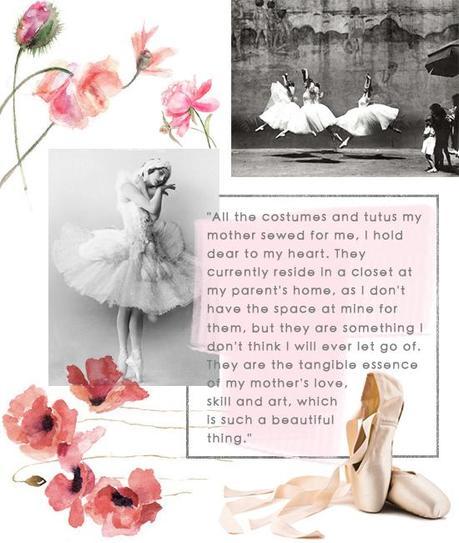

“My mother started out sewing me very simple tutus. When you are in the single digits, costumes are never too elaborate. The first one was a 3 layer, rainbow colored tutu attached to a yoke that was fitted at the waist and hips. I still remember this tutu fondly. And I’m sure it’s still stashed away somewhere in my parent’s home As I grew older, tutus became a little more difficult, and tried on my mother’s patience for sure. She sewed me a few romantic tutus, which have 3-9 layers, and require a lot of weight lifting to manage the volume of all the net. A pancake tutu, which has about 9-12 layers, is by far one of the most difficult ones to make. She would spend hours tacking layers together, trying to achieve the flat “pancake” look. These tutus could take her anywhere from 30-80 hours to complete,” wrote Alex, the owner of Larkspur, one of my sponsors this month. Her memory of his mother sewing tutus is what first sparked my interest in this category of sewing and once I started investigating, it became clear to me why I’m drawn to the ballet and their tutus, and it’s the same reason why I have an obsession with wedding dresses – the amount of delicacy and work that it put into each piece astounds me.

Broadly speaking, a tutu is a dress made for a ballerina, consisting of a bodice with knickers and a skirt attached, but strictly speaking, a tutu is just the skirt portion of the costume. A tutu represents the visual grace of a performance and the dancers. Not only is it designed with beauty in mind but also functionality. A tutu is meant to enhance a performance and not restrict the ballerina. It’s structure is rigid, but also allows for give so that the dancer can move sinuously.

The tutu’s life began in the mid 1800s as a three-quarter length, bell-shaped skirt made of tulle. Called a romantic tutu, the hemline hit between the ankle and the knee and was free flowing to emphasis lightness. The modern day tutu, two versions being the pancake and the powder puff tutu, came onto the stage in the late 1800s / early 1900s to show off the ballerina’s more intricate feetwork.

The powder puff tutu is composed of approximately ten or more yards of net of varying thickness. The net is gathered and then put into layers with the number of layers varying from company to company and country to country. The softest layers are placed closest to the legs while the stiffest layers are placed in the middle and the top layers are placed somewhere in between the two. The layers are attached to a basque, which fits the dancers waist and hips are and are affixed to the knickers. The layers are then loosely tacked together to ensure that they move in sync. The final layer, the top skirt, is the heaviest and most intricate, with jewels, feathers, appliqués, and all other kinds of embellishments sewn to it. The pancake tutu that Alex referred to is similar to the powder puff tutu but it extends straight outwards (the powder puff is a slight bell shape), and uses a wire hoop to achieve its shape.

Some ballerinas love tutus and some loathe them, finding them uncomfortable and restrictive. Because they are not able to see their legs and feet, ballerinas rely on their partner for balance. The tutu can also be challenging for the ballerina’s partner. Most of the decoration on the top of the skirt will be placed slightly away from the waist, giving her partner a safe place to hold her so that his hands aren’t marred by the embellishments. Even then, he still has to watch out as the stiff net layers can scratch the skin.

Click here for hints and the history of the tutu.

Click here for an interesting interview of a modern day ballerina.

Click here to read about how American ballerinas are redefining the ballet.

Click here for a general overview of the tutu.