As an itinerant scholar, I've recently written a small piece about Verdi's Macbeth. The commissioning body doesn't know what it's unleashed. Among other things, it gave me the idea of starting a series of semi-scholarly summaries here, featuring historical background, colorful anecdotes, and a highly subjective selection of recommended reading and listening. As has been intermittently obvious on this blog, going to the research library as preparation for attending an opera performance is my idea of a good time. It would seem that I have a kindred spirit in Verdi himself; he paid a great deal of attention to the historical setting of Shakespeare's Macbeth, writing to his publisher and set-designer about political details of eleventh-century England and Scotland.

As an itinerant scholar, I've recently written a small piece about Verdi's Macbeth. The commissioning body doesn't know what it's unleashed. Among other things, it gave me the idea of starting a series of semi-scholarly summaries here, featuring historical background, colorful anecdotes, and a highly subjective selection of recommended reading and listening. As has been intermittently obvious on this blog, going to the research library as preparation for attending an opera performance is my idea of a good time. It would seem that I have a kindred spirit in Verdi himself; he paid a great deal of attention to the historical setting of Shakespeare's Macbeth, writing to his publisher and set-designer about political details of eleventh-century England and Scotland.Macbeth was Verdi's own favorite opera at the time of writing. In 1864, however, when undertaking substantial revisions, he wrote of parts of it as "weak, or even worse, lacking in character." The mid-twentieth century saw a brief revival of the 1847 version, and in recent years, both versions have found place on the operatic stage. The work's very unconventionalities - to judge by essays and interviews - helped it to a mini-boom in the early years of the twenty-first century. (I've written about performances I've seen at the Met here and here.) Macbeth was Verdi's first foray into adapting Shakespeare, and he was unsurprisingly perfectionistic in working with Piave on the libretto, intent on having language echo feeling and fit with musical form.

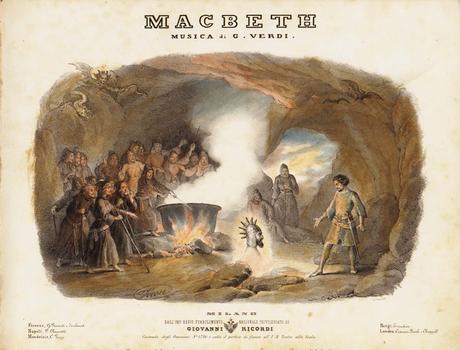

Some tropes of Romantic opera are gloriously indulged in; witness Lady Macbeth's fabulous letter scene, and the deeply creepy witches. Others are abandoned, apparently without a backward glance. No young lovers are here, no tyrannical fathers. Verdi experimented with the dramatic order of his desired scenes, as well... notably carrying this even further in the revisions, scrapping Macbeth's final aria in favor of the haunting, stirring chorus celebrating the tyrant's downfall.

"Don't try to economize on the size of the chorus," Verdi wrote, "and you won't regret it." The chorus is a character in its own right, departing from Shakespeare and dramatizing Verdi's political convictions. I rather love the fact that the tyranny of the Macbeths is not solely - or even primarily - opposed by the heroic tenors, but rather by the chorus as a whole. An anecdote I love says that early audiences would throw bouquets beribboned in the Italian colors of red and green on stage... until the police forbade it. At this juncture, audiences duly switched to ribbons in the Austrian colors, which the singers consistently refused to pick up.

Verdi was also intent on achieving some very specific dramatic effects in Macbeth. For the apparition of kings, he wrote "This little orchestra of two oboes, six clarinets in A, two bassoons and one contra-bassoon, produces a sonority which is strange and mysterious, yet at the same time calm and quiet." He wanted the musicians under an open trap-door so that the sound would spread through the theater "in a mysterious manner and as though from a great distance." Verdi wrote in a letter in December of 1846 that the ghost of Banquo should be played by Banquo's actor, covered in a gauzy veil, and "with his hair ruffled and a few wounds visible on his neck." Verdi seems to have anticipated some resistance to his minute directions, as he clarified that were based on what he'd found out about performances of Shakespeare in London, "where they have been performing this tragedy continually for more than 200 years." Verdi was particularly irked when one of his Banquos did not cooperate, writing: "The singers must be engaged to sing and act... it's high time we stopped being so easy-going about this kind of thing." The high-point of journalistic blather about operatic acting as an alleged novelty may have been reached some years ago (I hope) but I plan on countering any further examples of such with Verdi's 1847 dictum.

Selective listening roundup: I listened to a lot of Macduffs and cried. I also listened to a lot of Lady Macbeths (Ladies Macbeth?) because she's magnificent. Verrett is mesmerizing. Netrebko makes terrible ideas seem irresistible. Callas sings the Lady in concert and still looks like she could and would kill a king. Probably without getting blood on her dress.

Subjective Bibliography: The Verdi Companion

Letters Of Giuseppe Verdi.