This evening sees the opening of Franco Alfano's Cyrano de Bergerac at the Met. It's being marketed as Puccini-like, but the comparison, in my view, over-simplifies the work of both composers. To me, Alfano's Cyrano seems a curious blend of romantic structure and dramatic spectacle, and experimentation in orchestral explorations of the central characters' psyches. I'd be inclined to say that it provides, as Alexandra Wilson has suggested for the late works of Puccini, a sort of alternate vision of how modern opera might have developed in the Italian tradition. From a scholarly perspective, it's received comparatively little attention, even when measured against Alfano's other works. I was surprised to discover this, given my personal fascination with how Alfano's opera functions as an adaptation of Edmond Rostand's 1898 play, which is itself a homage to the five-act dramas of France's golden age of theater in the seventeenth century. I grew up with an edition illustrated by Dubout, and, later, wore out a VHS of the Gérard Dépardieu film; this is one opera I came to via its source text, rather than the other way around.

This evening sees the opening of Franco Alfano's Cyrano de Bergerac at the Met. It's being marketed as Puccini-like, but the comparison, in my view, over-simplifies the work of both composers. To me, Alfano's Cyrano seems a curious blend of romantic structure and dramatic spectacle, and experimentation in orchestral explorations of the central characters' psyches. I'd be inclined to say that it provides, as Alexandra Wilson has suggested for the late works of Puccini, a sort of alternate vision of how modern opera might have developed in the Italian tradition. From a scholarly perspective, it's received comparatively little attention, even when measured against Alfano's other works. I was surprised to discover this, given my personal fascination with how Alfano's opera functions as an adaptation of Edmond Rostand's 1898 play, which is itself a homage to the five-act dramas of France's golden age of theater in the seventeenth century. I grew up with an edition illustrated by Dubout, and, later, wore out a VHS of the Gérard Dépardieu film; this is one opera I came to via its source text, rather than the other way around.Cyrano de Bergerac, subtitled as a commedia eroica, was first performed in the Paris of 1936. I thought that the choice to write an opera based on a heroic fighter of doomed causes in the increasingly totalitarian Europe of the 1930s might have been a political one; but Alfano's ties to Mussolini belie this naively romantic hypothesis.The libretto, which preserves much of Rostand's gorgeously ornate language, is by Henri Cain, a frequent librettist of Massenet's, whose texts include Cendrillon, La Navarraise, and Don Quichotte. For me, as an aficionado of the play, it is curious to hear a text with such strong rhythms, such strong music of its own, orchestrated for the opera stage. But the results are often strikingly poignant. One of the things I find most interesting about Cyrano, in fact, is how the music sometimes undermines the apparent optimism of the text. Trumpets promise discord and warlike tumult even as Cyrano and Christian, the piece's rival tenors, embrace for the first time. When the two men promise brotherhood, the orchestra foretells disaster.

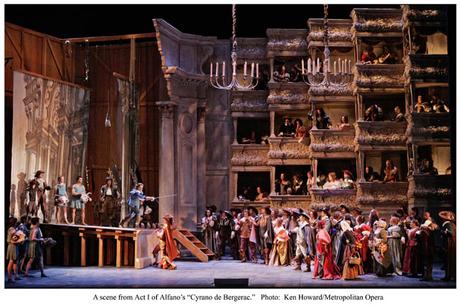

The vocal writing of Cyrano owes something to Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, in Julian Budden's assessment. It's not a resemblance that I had noted in previous listenings, so different are the moods and settings of the works, but there are audible similarities between Mélisande's balcony scene and Roxane's. Throughout, Alfano's music makes the melancholy underlying even Cyrano's most triumphant moments inescapable. The great Act I set piece at the theater is characterized by dissonances that are unresolved, by long, yearning phrases, and by the voice of Cyrano, whether as poet or as fighter, set against those of all others on stage. It is telling that much of Cyrano's great personal manifesto, in Act II, is entirely unaccompanied, as are his moments of greatest frankness -- of ecstasy and anguish -- in the balcony scene. Roberto Alagna has made the central role his own; but the work offers other highlights as well. The "Voici les cadets de Gascogne, de Carbon de Castel-Jaloux!" is stirring and should make a great moment for the Met's superb men's chorus. In many ways, it seems to me, Alfano's comparatively neglected work is a good use of the Met's resources. It's an interesting score, seldom performed, and therefore of interest to opera obsessives. At the same time, it's unapologetically romantic, and thus likely to be attractive to devotees of nineteenth-century opera's greatest hits. Having a star of Alagna's magnitude and the rising soprano Jennifer Rowley perform alongside each other is the kind of decision I wish the Met would make more often. I won't be able to see this run, but I hope you'll tell me if you do, Gentle Readers.