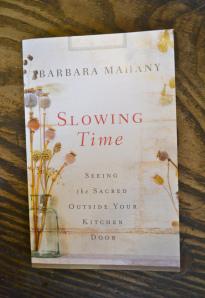

Barbara Mahany describes her new book as a field guide to wonder. The essays in Slowing Time: Seeing the Sacred Outside Your Kitchen Door at times bring to mind Wendell Berry, Mary Oliver, Anne Lamott, Karen Maezen Miller, Waldorf pedagogy, and mystics including Julian of Norwich. Mahany leads us through the cycle of seasons in the natural world, and in the life of a Christian and Jewish interfaith family. A former Chicago Tribune columnist (and former pediatric oncology nurse), Mahany writes as a parent, a naturalist, and a Catholic. Her voice—funny, humble, brave, affectionate—narrates this unusual volume, pulling together disparate elements into a moving whole, lovely in both form and content.

So, at the bottom of each page we find a running commentary of poetic field notes on the moon and other astronomical and agricultural changes through the year. Each section ends with a recipe, reflecting the spiritual and seasonal bounty (beginning and ending with winter, which gets two sections, and thus two recipes). And each season begins with notes acknowledging the agrarians roots of Jewish and Christian and secular holidays, and providing suggestions on how to infuse these celebrations with new meaning.

For example, I love this entry on the spring calendar, for a holiday with Pagan origins: May Day (May 1): Caretaker of Wonder Pledge: I will rescue broken flowers and ferry them to my windowsill infirmary, where I’ll apply remedies and potions, or simply watch them die away in peace.

In this one brief and surprising sentence, Mahany manages to avoid both the saccharine and the how-to, instead reflecting on the hard truths of the natural world, providing insight into her interactive and intentional approach to marking the seasons, and perhaps provoking us to join her in this novel contemplative activity.

For me, the fact that Mahany writes as a Catholic woman married to a Jewish man, raising children with both religions, provides an important key to experiencing Slowing Time. (For more on Mahany’s interfaith family story, listen here to her wonderful Holy Rascals interview with Rabbi Rami Shapiro). Often, I am asked if interfaith families celebrating both religions end up with a dry, intellectual approach, devoid of spirituality, as if we are studying the religions in a museum or academic course, comparing and contrasting, with all the sacred juice drained out.

These questions come from people who have never experienced life inside an interfaith family like Mahany’s. I like to say that we are religious maximalists, not minimalists, celebrating both, rather than nothing. Indirectly, quietly, without arguing or defending or setting out data (as I must do as an advocate and journalist), Mahany makes the case for the rich spiritual lives of interfaith families who intentionally immerse themselves in the earthly connections, and particularities, of these two sibling religions.

Or, as Mahany writes, while her family “encounters the Divine in the rituals and idioms of two faith traditions,” she finds that “the dual lenses refract and magnify both light and shadow, and that my sense of the sacred pulses throughout the year.” The sense of sacred pulses throughout this book, and throughout the lives of those of us who draw meaning and take inspiration from more than one ancestral religion. I am grateful to Mahany for her deep consideration of how this looks and works and feels for her, through many small moments, keenly observed.