As lead book reviewer for the New Statesman, John Gray has a superb platform for elucidating, in wonderfully acidic prose, the kludgish philosophy of John Gray. The books themselves seem to be an afterthought, mere vehicles for the critical scorn Gray so often pours on the secular faith in progress. In his most recent review, of Karen Armstrong’s Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence, Gray takes aim at the rationalist prophets of that faith: evangelical atheists. He also happens to like Armstrong’s book, which is a bit surprising. Before Gray gets to her book, he diagnoses the historical and cultural angst that may be motivating these prophets:

The idea that religion is fading away has been replaced in conventional wisdom by the notion that religion lies behind most of the world’s conflicts. Many among the present crop of atheists hold both ideas at the same time. They will fulminate against religion, declaring that it is responsible for much of the violence of the present time, then a moment later tell you with equally dogmatic fervour that religion is in rapid decline. Of course it’s a mistake to expect logic from rationalists. More than anything else, the evangelical atheism of recent years is a symptom of moral panic. Worldwide secularisation, which was believed to be an integral part of the [progressive cultural evolutionary] process of becoming modern, shows no signs of happening. Quite the contrary: in much of the world, religion is in the ascendant. For many people the result is a condition of acute cognitive dissonance.

This is classic Gray: heavy on rhetoric and light on argument. His own fulmination would fall flat without further analysis, which Gray then provides:

It’s a confusion compounded by the lack of understanding, among those who issue blanket condemnations of religion, of what being religious means for most of humankind. As Armstrong writes [echoing Talal Asad], “Our modern western conception of religion is idiosyncratic and eccentric.” In the west we think of religion as “a coherent system of obligatory beliefs, institutions and rituals, centering on a supernatural God, whose practice is essentially private and hermetically sealed off from all ‘secular’ activities”. But this narrow, provincial conception, which is so often invoked by contemporary unbelievers, is the product of a particular history and a specific version of [western Christian] monotheism.

Atheists think of religion as a system of supernatural belief, but the idea of the supernatural presupposes a distinct sort of cosmogony – typically one in which the material world is the creation of a personal God – that is found in only a few of the world’s religions. Moreover, the idea that belief is central in religion makes sense only when religion means having a creed.

Throughout much of history and all of prehistory, “religion” meant practice – and not just in some special area of life. Belief has not been central to most of the world’s religions; indeed, in some traditions it has been seen as an impediment to spiritual life. Vedanta, Buddhism and Taoism caution against mistaking human concepts for ultimate realities; Judaism, Christianity and Islam all contain currents of what is known as apophatic theology, in which God can be described only in negative terms. It is only those who are hung up on creeds who become missionaries of unbelief.

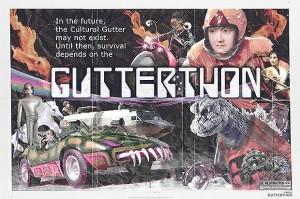

Gray’s last sentence hits at least one nail squarely on the head. Evangelical atheism is dialectically engaged with an historically particular and peculiar form of western Christian religion. To combat this creedal form and its Abrahamic relatives, atheists fight on a field of theist choosing. Because the parameters of this debate have been established by western theists, evangelical atheists counter with a series of conceptual inversions. Ironically, this forces a mirror substitution of one metaphysics for another. While this may be well and good within the confines of the cultural and philosophical gutter, where large numbers of people happen to reside, it offers precious little to those not bound by the tedious binaries of belief/unbelief and theism/atheism.