Henry Gustav Molaison is one of the most famous patients in the annals of brain research. In 1953, an experimental surgery meant to relieve his severe epilepsy rendered him frozen in time: He could remember events and facts he knew before the surgery, but could retain virtually nothing after. For decades, Molaison (who’s known as H.M. in psychology textbooks and scores of research papers) cooperated with researchers interested in what his strange memory deficit could teach them about how the brain creates a record of faces, facts, and life experiences.

When Molaison died in 2008, his brain was painstakingly preserved. Now it’s available online for scientists (or others who request permission) to explore, right down to the level of its cellular architecture.

At the time of Molaison’s surgery, the conventional wisdom was that memory traces were distributed throughout the brain. But his case showed that certain parts of the brain were essential for certain memory functions. The surgeon, William Beecher Scoville, had removed large parts of the medial temporal lobes, including the hippocampus. If this structure gets taken offline, we now know, a person can’t form new memories of people, places, things, and events. Molaison, for example, would greet researchers who’d worked with him for decades as if he’d never seen them before.

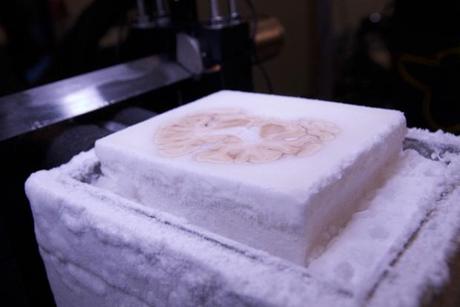

When Molaison died, at age 82, the task of preserving his brain fell to Jacopo Annese, a neuroanatomist at the University of California, San Diego and director of the independent, non-profit Brain Observatory. Annese froze the brain inside a block of gelatin and sliced it into 2,401 paper-thin sections in a marathon 53-hour slicing session in 2009. As if the pressure of handling such a delicate and precious object wasn’t enough, Annese streamed the cutting live on the internet, in the name of bringing the science to the people (his website got 400,000 visits during the procedure).

Annese’s goal is to create an open-access atlas of Molaison’s brain for historical preservation and scientific study. A paper published today in Nature Communications describes some preliminary findings and provides the most detailed look yet at the brain damage that caused Molaison’s memory problems.

It turns out that Scoville did not remove the entire hippocampus as he’d intended. Instead, his suction tool only got roughly the front half of the hippocampus on each side of the brain, as well as the nearby entorhinal cortex, and much of the amygdala. MRI studies conducted when Molaison was alive reached similar conclusions, but the new post-mortem examination shows the surgical lesions in far greater resolution. Under the microscope, there’s evidence of healthy-looking neurons in the part of the hippocampus that was spared, Annese says.

The damage to Molaison’s entorhinal cortex, rather than to the hippocampus itself, is almost certainly what caused his memory deficit, says Suzanne Corkin, a neuroscientist at MIT who worked with Molaison for nearly 50 years (and is also an author on the new paper). “The entorhinal cortex contains all the the pathways that bring information from the outside world, from all of the senses, to the hippocampus,” Corkin said. Without that connection, whatever remained of Molaison’s hippocampal memory-making machinery was completely cut off. It might as well have existed in a vacuum.

The post-mortem exam also found evidence of a small lesion in the frontal lobe. It’s possible that this damage happened during the surgery 60 years ago, Corkin says, but it’s also possible it occurred much later in his life. The digital atlas gives researchers a new tool to study that and other questions, such as the nature of the dementia that robbed Molaison of language near the end of his life. “Years of work are still to come,” Corkin says. The new study isn’t the final word on Molaison’s brain, she says. It’s more like the opening of a new chapter in one of the longest case studies in the history of science.